The Magic Circle is a puzzle exploration game set inside vapourware

BioShock 2 director Jordan Thomas turns the immersive sim inside out.

It's fashionable for game developers to show their working these days, so it's no huge surprise when Irrational alumnus Jordan Thomas reveals that his first game since going indie, The Magic Circle, is about the clash of interesting systems in an unfinished setting. But this is no alpha version and you're not invited to contribute to the game's development. Instead The Magic Circle is set in a fictional unfinished game world, and you play an unfinished hero rebelling against the developers' lack of progress.

That might sound like a departure for a man best known for his contributions to the BioShock series - having masterminded Fort Frolic in the original game, Thomas was creative director on BioShock 2 and returned to Irrational to help make Infinite - but another way to look at it is that he has spent a lot of time working on interactive dystopian allegories, which actually seems like quite a good way to describe a game set inside development hell.

"Speaking only for myself, from outside the industry game developers seemed larger than life to me," Thomas explains. "All that old hyperbole about 'Game Gods' - I bought it hook, line and sinker. They had taken on the seemingly impossible task of manufacturing a plausible alternate reality and convincing me to live there for a while. The truth, of course, is far more flawed, far more human - and I would argue more interesting.

"Candidly, it also just struck me as funny to engage in one of these quixotically ambitious, eternally revised projects from the game's eye view. And the idea that you are not in good hands, that the game's designers do not have your back this time (and in fact can't even decide on your powers, so you have no direct way to influence the world at all), so you're going to have to un-FUBAR the world yourself, held a kind of promethean scrappiness that really appeals to me."

But forget all that. The Magic Circle will undoubtedly have a lot of the developer's experience and worldview balled up inside it (and that of his partner at Question Games, Stephen Alexander, another Irrational man, and AI specialist Kain Shin, who worked on Thief 3 and Dishonored), but those layers are likely to be subtle and more fun to pick over afterwards. Your immediate business as the player is with a first-person puzzle exploration game that has a unique art style and a fantastically cool central game mechanic.

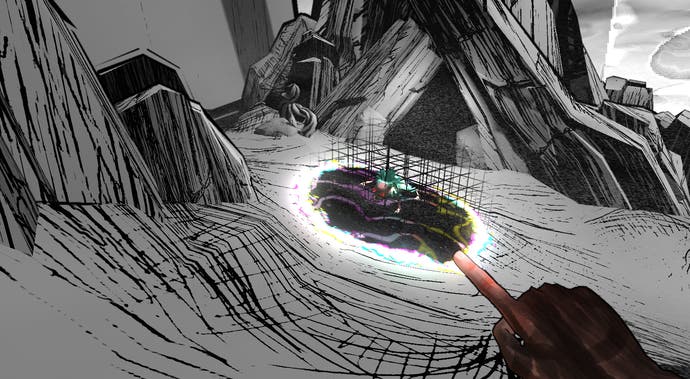

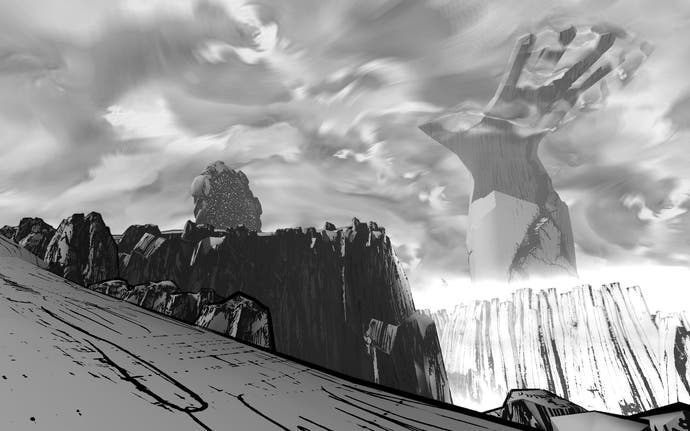

The Magic Circle is set inside a high-fantasy remake of a fictional 80s text adventure, also called The Magic Circle, that has been in production for many years. The original was made by Ish Gilder, "a mild-mannered game designer who won't let us call him a genius" in the words of a fake website for the game. An audio diary early on (of course there are audio diaries) reveals that The Magic Circle has been in production for two decades. It's vapourware. The environment resembles a whiteboard outline that has been erased and redrawn - a beautiful, sinewy vision of sketch lines and uncertain clouds, with only occasional flashes of colour showing live elements.

As you spawn into the world - who you are isn't exactly clear, but you seem to be the game hero - you come face to face with a disembodied stone head apparently known as Old Pro, who starts cluing you in to what's going on. Or at least he clues you into his take on it. Apparently unaware he's in a game, Old Pro perceives his surroundings as reality and regards the game developers as meddling gods "with s*** for brains". But he has one up on them: he knows how to manipulate their universe and you are his instrument, syphoning energy out of colourful fissures and using it to reprogram elements of the world, like enemies, by drawing a literal magic circle around them and altering their behaviour.

Old Pro hopes you can do something about those meddling developer gods, but it's important to remember they are still in control, and there's an early illustration of this when you try to create a bridge by using the magic circle to undelete some of the environment. Suddenly everything freezes and a floating eyeball appears and starts moving things around - deleting your bridge and shuffling the heights and positions of nearby rocks like a designer fiddling with a WYSIWYG interface. "That thing does the gods' dirty work," explains Old Pro. "I call it the Sky Bastard... Now, if you were to pull some stunt, something whizz-bang enough to keep that flying f***toy occupied, we can maybe trap it."

With the battle lines drawn, you get to explore the game a bit more and your magic circle ability quickly shows its potential. The first enemy you encounter is the Howler, a scrawny little four-legged critter who comes bounding over as soon as you're in sight. Trapping him in a magic circle allows you to approach unmolested and bring up a sort of debug menu that lists his behavioural patterns in simple commands. I move by [Ground]. I attack with [Melee]. My enemies are [THE HERO]. My allies are [Nothing].

These debug menus float around as the player moves the cursor, as though you're reading stuff printed on the inside of the Howler's little AI head, and a bit of judicious editing follows. My enemies are [Nothing]. My allies are [THE HERO]. Releasing the Howler from the magic circle, he skips after you like a pet. As you approach more Howlers, your new friend attacks them and takes them out.

In the tradition of the immersive sims they cut their teeth on, Thomas and co are designing broad spaces in The Magic Circle that lend themselves to exploration and experimentation, and the possibilities afforded by your unique ability multiply as you get to move around one of these - a grassy plain bordered by ruins and caves and a volcano spitting molten globules of colourless lava. You can only do so many things with the magic circle at once - each circle uses a bit of your life bar, which is a finite resource - but this sort of restriction usually focuses creativity rather than hampering it.

Certainly the tools are there to suggest it will. Another interesting setting on the Howler's debug menu was Copy All Behaviours. Essentially, the magic circle can learn new ways to manipulate things in the fictional game world once you've seen them in action. When you come across little enemies called Hivers, you can trace the force influencing them by following shooting sparks of light and darkness, which leads you to the Hiver Queen, and you can then trap her in a circle, program her to stop attacking you and copy the special Groupthink ability she was using to control the smaller Hivers.

Ignoring the Hivers now - severed from their Queen, they ignore you too and sit around listlessly - you make for a gaggle of Howlers. You're unable to trap a large group with the magic circle - you don't have enough life force - but by picking one off, you can install the Groupthink ability and tell it to be your friend. Now whenever you come across other Howlers, they're on your side. When you approach the volcano, which is being guarded by fiery little mounds of pain called Flamers, you can program a single Howler to take them out, and with Groupthink in play they all pile in.

It's a basic strategy, but the point is you could have done anything you liked. Maybe you didn't find Groupthink but you did locate a special Rock that has a Fireproof ability, and you applied that to your original Howler pet, allowing him to rip the Flamers to pieces one by one, impervious to their attacks. And if you found Groupthink and Fireproof, allies under Groupthink's control would inherit Fireproof once it was applied to one of them, giving you a little flame-retardant army. The actions are simple at this point, but it doesn't take much of a leap to imagine how diverse and entertaining they might become later on, or to see the potential for these simple systems to combine in inventive ways. Look at the original lines of the Howler's menu. What if you don't move by [Ground], for instance?

"Players are constantly talking about how they, personally, would make a game better," says Thomas. "I enjoyed the idea of harnessing that impulse, asking you to solve puzzles by authoring solutions from a big palette of options instead of merely uncovering the designer's intent. So while your solution to a given challenge may be rough-edged as hell and lack the machined, clockwork feel of other puzzle games, you feel like it's your own. The hope is that you're having enough fun that you don't realise you're coming up with your own rules."

Although the gameplay is principally focused on stealing, changing and remixing AI behaviour - "if it's not nailed down, you can make it stand up and dance like one of Mickey's brooms," says Thomas - the fact the environment you're exploring is supposed to be unfinished, layered with ideas and spaces that have been built and not quite deleted over two decades of game development indecision, means that the exact extent of the story and the mechanics is still tantalisingly unpredictable.

For example, if the idea of a game set inside a fictional game that isn't finished yet isn't meta enough, at one stage the Magic Circle game world intersects with the world of another fictional game, perhaps an abandoned attempt to reboot The Magic Circle in another style, allowing you to roam around a dark spaceship interior designed to appear to you as a low-res region in an otherwise modern game. It's a trick we've seen before - most recently in Wolfenstein: The New Order - but this is clearly more than a gag and has been lovingly composed, complete with aliasing around objects, fake pixel crawl and mushy textures. Perhaps you can copy behaviours from this other space, too? In this unfinished setting, anything seems possible, which is a best feeling a game can give you.

"We're three humans, making this, so we needed a fairly strict organising principle," says Thomas. "It does escalate, as you gain more and more creative influence over the game world - but it's not intended to become a 20-hour investment. We respect the player's time in such a weird frame of mind - and don't want to overstay our welcome."

Keeping it trim should also help Thomas, Alexander and Shin hit their target of shipping for PC and Mac in 2015 (they are hopeful of being able to self-publish on consoles too, but it may be after the initial release). "We know we want to be out next year," says Thomas, "but we're leery of promising a date with a systems-driven game... that for some addled reason is also claiming to contain a strong narrative component."

And there's another reason the developers are keen to be out on time, of course. "We're applying internal pressure towards a date for sanity's sake - but we, uh, really, really, really don't want to fall into the trap of eternally promising and failing to deliver," says Thomas.

"The irony, given our themes, would be thick enough to leave a film on your glasses."