The joy of treating demos like a finished game

Discworlds.

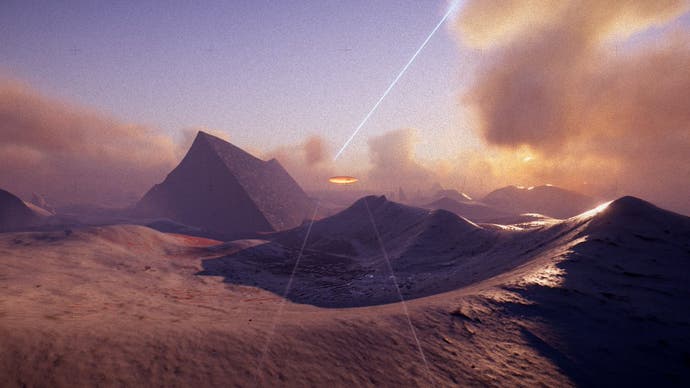

There are many worlds in Jay Weston's Exo One, but I'm not sure I want to leave the one you explore in the game's Steam demo. I love hurtling towards its whirling horizon so much I would hate to actually cross it. If you've yet to have the pleasure, Exo One is a scifi-me-do of monolithic abstraction and giddy kinesis, like a pinball table built by the aliens from 2001: A Space Odyssey. It puts you in charge of a gleaming craft that can tumble over planets as a silver orb or squash itself into a flying disc, generating energy for movement from surface friction.

The demo gives you 10 minutes to revel in all this, and much as I'm tantalised by the planets that await, I do wonder whether its timed fade-to-black is a more appropriate ending than any the final game might provide. Exo One, you see, is a story of first contact. One of its planets is named for the astronomer Carl Sagan, who spent his career devising messages to the stars or hypothesising about conditions for life on other planets (the game's rushing perspectives, always plunging toward and through some celestial object, also recall the voyages of Sagan's celebrated Cosmos TV documentaries). Given the enormity and longevity of the universe, it's extremely unlikely that our species will encounter another star-faring civilisation before we're eaten alive by our sun or our own excesses. A fade-to-black is, sorry to say, the more likely outcome.

But perhaps I don't need to be quite this high-faluting. Perhaps the source of the demo's enchantment isn't that accidentally poignant resolution but a quality all demos share - the unspoken invitation to get as much as you can out of something incomplete and disposable. There are many ways to replay Exo One's demo. You can treat it as a time trial, of course, coaxing every last inch of airtime out of every rise, throwing yourself into driving rain. Or you can dial back your need for speed and turn it into an endlessly recurring final act of wandering and contemplation, comparable to Ko-Op Mode's Orchids To Dusk. You might slow to watch sunlight bronze the dunes and listen to the crackle of dirt under chrome. You can trace patterns in the clouds, particularly the shapes revealed by lightning flashes, instead of powering through them. And then there are those huge, geometric structures that burst from the sand - the usual alien relics, or something even more obscure? These are things you can puzzle over in the full game, of course, but as always in demos, your awareness of being deliberately hemmed in is a powerful goad.

The videogame demo is something of a weird relic itself, suffused with nostalgia. Not so much nostalgia for the act of playing an incomplete game, mind you - between Steam festivals and Early Access, free-to-play "core" editions, multiplayer betas and countless works-in-progress on itch.io, we are hardly lacking for demos or demo-type experiences today. Rather, it's nostalgia for an age still defined by physical media, when discs were jealously hoarded magic portals rather than the prelude to a downloadable update, and the embryonic internet was a Lost-Woods-esque tangle of hidden paths and shareware grottos, rather than a pervasive apparatus of recommendation algorithms.

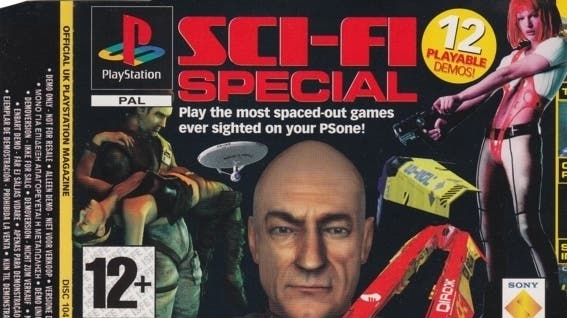

90s-era demos, and especially the CD-ROM compilations given away with gaming magazines, had an illicit, cultish charm. I used to trade them in the playground alongside mix-tapes of dodgy electronic bands and the Beach Boys. Some demo discs were duds, cynically padded out with trailers and save files for games I didn't own. Others were collector's items: as a budding space cowboy, I set particular store by OPM UK disc 104, with its triple-whammy of two Colony Wars demos plus WipEout 2097. As kids, we'd gather at sleepovers to pick through the contents of these demos. And we'd also try to break them, to force a path through them into a final game we couldn't afford.

Looking back, I think of my experiences with game demos as a process of creative antagonism, almost equivalent to found object art-making, because a demo is essentially an exercise in keeping things from you. A good demo is a tight balance of seductive and abrasive. It wants to entice you into a purchase but to do that, it has to frustrate you, sating you just enough then whipping the carpet away. So you try to frustrate the demo in turn. You deny the thing its status as a disposable prelude, a means of earning preorders - you treat it, instead, as something complete and valuable, a junky little pocket of virtual spacetime that is uniquely "yours" because you insist on calling it treasure. You revisit it again and again, doing everything you can with what it contains. You poke your nose into every corner, hoping against hope that a door will slam open and you'll drop through into a larger world. You polish your playthroughs till enemies and obstacles are just props you use to express yourself, dancers in a routine you can manipulate at whim. You speculate about the things the demo doesn't say, writing stories of your own; nowadays, of course, fomenting this kind of intrigue is a standard plank of any blockbuster marketing campaign.

In the process of playing and replaying demos, refusing to accept their status as commercial ephemera, you become part of a community. Before writing this piece I asked people on Twitter about their favourite game demos, and was drowned in responses from developers, players and journalists all celebrating the ways in which they gotten more out of these demos than was strictly permitted. You know the kind of thing: replaying a VirtuaCop demo with your own rules, such as only scoring shots to the knee. Hacking the timer in the Grand Theft Auto demo, or just focusing on its version of the city simulation, which is pretty complete, rather than trying to beat missions against the clock. Some developers were generous with demos to a fault: take the unfortunate creators of Robocod on the Amiga, who accidentally gave away their entire game after forgetting to disable a level select cheat code.

Most coveted of all are the demos that harbour development materials cut from the final game, like Resident Evil 2's Director's Cut demo. These are priceless historical finds, but even without such a payload of fossils from an aborted timeline, a demo is always already a distinct creation. To release part of something as a standalone experience is to change its meaning. I have bought and played eight WipEout games, but when I think of WipEout the first thing that comes to mind is Gare D'Europe, the 2097 track given away with OPM 104. That disused metro station, overlooked by passing trains, is for me a game itself - a parallel reality stripped of the series' famous music. Demos also come to mean different things when they're jumbled into magazine-cover compilations, together forming a kind of gallery exhibition of complementary or contrasting experiences. The OPM 104 disc is an opportunity to place different conceptions of outer space against each other, the streaking deep-sea particles of Colony Wars versus the cavernous, creeping backdrops of R-Type Delta. Exo One's demo would have plugged in nicely.

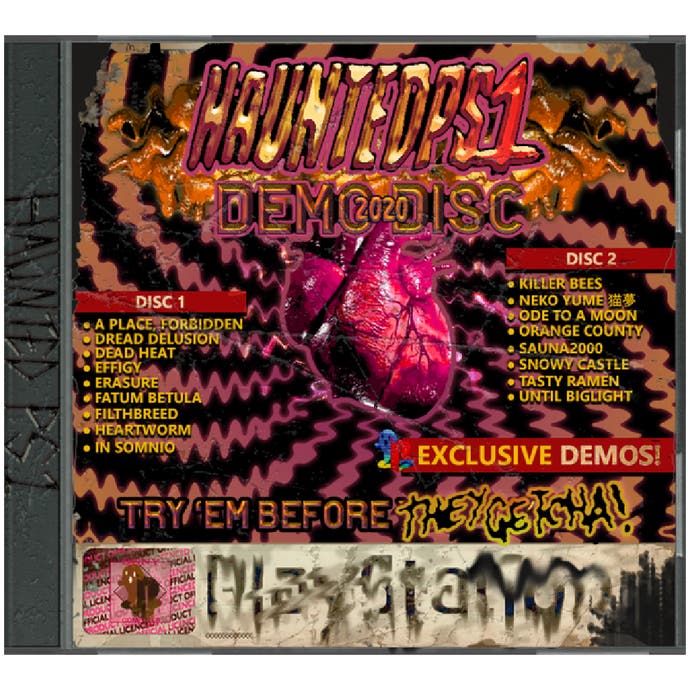

The demo disc ethic has been channelled by latter-day indie anthologies such as Haunted Demo Disc 2020 and the Dread X Collections, whose creators were also inspired by Konami's PT teaser for the unreleased Silent Hills. PT might be the ultimate demo, to my mind, because it makes revisiting a space in search of new things to do a question of life or death. Miss a detail, and it's curtains on your next runthrough. It's hard to imagine Silent Hills being as well-received as PT was, because Silent Hills was after all the work of Hideo Kojima, whose games are giant, creaking crates of odds and ends, wobbling back and forth between genius and idiocy. That eccentricity can be obnoxious when you stretch it across a landscape as grand as Death Stranding's America, but pack it down into a hallway with a blindspot and the intricacy is hypnotic. A demo such as this is a reminder that you don't need a vast playspace to foster a sense of size; indeed, literal scale often seems to cramp the imaginations of otherwise gifted developers. The bigger gameworlds become, the more laborious they are to produce, and the more crushing and repetitive the interaction options they contain. There's much to gain from taking a chapter, an area, a character, an object and seeing how it holds up in isolation.

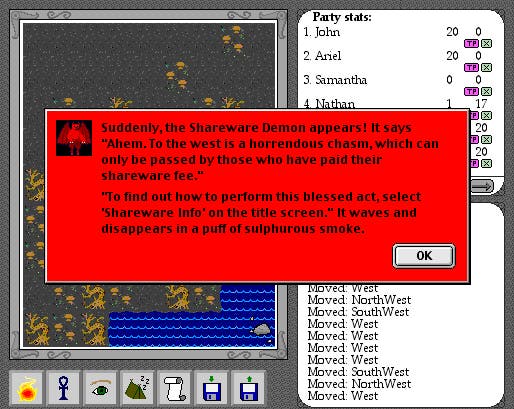

Writing this piece has made me realise that most of my childhood games were actually demos and shareware games, with one particular Macintosh floppy disc a precious belonging well into my teens: I used to carry it around in a sock. It housed a shareware version of Exile: Escape from the Pit, a wonderful party-based role-playing game from Spiderweb Software. Set out west in the unlicensed edition of Exile (latterly reinvented as the Avernum series) and you'll eventually run into a chasm, splitting the map down the middle. A sympathetic Shareware Demon notifies you that if you pay up, the chasm will be filled in. Instead, I turned the chasm into a landmark, something to set my back against during perilous journeys through wastelands patrolled by lizardmen bandits. Like a Dark Age astronomer speculating about life south of the equator, I wrote extravagant stories about the settlements, dungeons and people across the gap. As with the Exo One demo, Exile became for me a fiction defined and, in a way, strengthened by an impassable horizon. I still haven't played the full game.