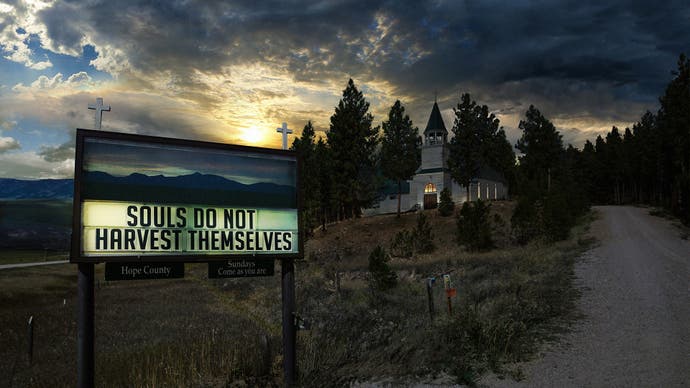

The history of violence buried deep in Far Cry 5's landscape

The first frontier.

Editor's note: Once a month we're graced with the brilliant presence of Gareth Damian Martin, author of the zine Heterotopias, creator of upcoming game In Other Waters and, most recently, author of The Continuous City, a book of analogue photography of video games, which is now available for pre-order.

Over the past few months leading up to the games release, there's been a strange sense that Far Cry 5's choice of a US setting means that the now venerable series is 'coming home'. It's something I've seen echoed in the coverage of the game, which is especially strange considering that the series was created in Germany, and originally set in Micronesia, and now sits in the hands of Ubisoft Montreal - the Canadian arm of a French company. How is it that a series defined by a surprisingly diverse set of landscapes, inspired by everything from the South pacific to Nepal could be 'coming home' to the wide-spaces and small-towns of Montana?

Perhaps it stems from the fact that the original game's protagonist, the generically named Jack Carver, was an American (ex-special forces, naturally) stranded far from home. And if anything connects the Far Cry games, beyond the clearing of enemy outposts and hunting of assorted animals, it is perhaps this sense of distance. Exotic is the word Ubisoft uses, often unflinchingly, to describe these various settings.

The implication is obvious, these are not our homes, our landscapes, our places, but those that belong to a wide variety of others. Far Cry has stretched this otherness to include not just generalised African revolutionaries and tattooed Islanders but even humanity's own prehistoric ancestors. You might say that, despite the recent games in the series being developed in Canada, the American identity of their audience has always been baked-in from the start. This is the world as seen through American eyes, a staging ground for expeditionary violence and unrestricted touristic freedom. Even the name of the series points to a world defined by distance and difference.

'Home', then, is an idea that has always been implied in Far Cry, a ghost landscape that is hidden beneath each of the exotic locales the series has presented. Much like the military backgrounds that the games' characters tend to have, all-too-neatly justifying their ability to handle firearms like seasoned soldiers, so this never-seen background of an American home acts as a neat way of framing the landscape we are playing in as "exotic".

I'd even go so far as saying that both this invisible landscape of an undefined American home, and the gestured at military backgrounds of many of the games' protagonists both serve the same purpose as the originator and justifier of the games violence: in Far Cry we solve problems with shooting because that's what we know how to do, and solving those problems is our responsibility because we represent America in its role as international problem solver. Ubisoft have tried to soften the unpalatable nature of this narrative over the course of the series, with Far Cry 4 casting the player as a protagonist born in, but estranged from, their Nepal-stand-in Kyrat, but they couldn't resist having him flee to America for most of his life before his return. It's as if all of the games exist in a world of only two landscapes, defined by the classical and deeply unpleasant colonial split of occident and orient. If someone is not in one they must be in another. This logic is unable to imagine anywhere else a refugee of Kyrat like Far Cry 4's Ajay Ghale could go.

So what does it mean when these two cross over? When the landscape of home and the exotic other overlap? What then is the origin point of the games' inevitable violence? The clue once again lies in a frame, a word, as problematic and politically fraught as the term 'exotic' and equally linked to the idea of landscape. That word is frontier. From repeatedly appearing in press coverage to the game's writer Drew Homes himself praising Montana's sense of 'frontier', this is a term that has come to be a key descriptive term for Far Cry 5's landscape. And what is fascinating about watching this term evolve in relation to the game is that it shows the series' inability to move past the colonial imagination of the world, even when turning its sights to its own occident.

Montana was of course, less than 150 years before the contemporary setting of Far Cry 5, a true frontier. In fact, in was one of the most violent and contested territories in the US, a battleground between the Native American tribes who had lived among its landscape for generations and the usurping colonial forces of the US Army. As you may know, it was in Montana that the infamous General Armstrong Custer fought and lost the battle of Little Big Horn. And it was in Montana, six years before, that 230 members of the Piegan Blackfeet tribe, mostly consisting of unarmed women and children, were massacred by US army cavalry and infantry in one of the worst events of its kind. Montana was the site of a string of battles in both the Sioux and Nez Perce wars, and one of the greatest stockpiles of Bison in the Northern US, with 17 million thought to be in the state in 1870. In less than two decades of hunting by America colonisers they would be extinct.

By framing Montana as a frontier, Far Cry 5, willingly or not, evokes this history. Far Cry 5's enemies are not Native Americans, they are instead religious extremists. But the games' choice of Montana as its 'frontier' cannot be separated from the history of that landscape and that word. It is a stark reminder that landscape is never the neutral ground we might cast it as. As Kenneth E. Foote puts it in his book Shadowed Ground: America's Landscapes of Violence and Tragedy these "sites of violence" are "inscriptions in the landscape" - they are written into the narratives of the land. So how does the virtual facsimile of Montana in Far Cry 5 relate to the real shadowed mountains of Montana? It is, of course, full of violence, over-flowing with it. As with each of the landscapes Far Cry had chosen before, this is not so much an expanse of natural territory as it is a playground. Everything is implicated into the constant ebb and flow of combat and conquering, from the wildlife that supply, fuel and even stage ad-hoc interventions into the games gun battles, to the bluffs and valleys that dictate the lines of sight, paths of assault and covered ground from which to choose your shots.

It is a landscape returned to a previous state, that of the frontier. It is a familiar American fantasy, one seen in The Last of Us and The Walking Dead - that the landscape of the US might become lawless once more, might be returned to the symbol it once was, of expansion, of mystery, of escape. A frontier. This idea, that the American landscape contains within it a core of violence, of unknowable distance, is one that has been explored almost comprehensively by the writer Cormac McCarthy. In his books, from the apocalyptic future of The Road to the contemporary decay of No Country for Old Men, he has two subjects, landscape and violence. And it is in his magnum Opus, the violent chronicle of a band of 'Indian Hunters' Blood Meridian that he most accurately sums up that connection, through the voice of the satanic Judge: "It makes no difference what men think of war, said the judge. War endures. As well ask men what they think of stone. War was always here. Before man was, war waited for him. The ultimate trade awaiting its ultimate practitioner. That is the way it was and will be. That way and not some other way." As the Judge later adds: "War is God."

In Far Cry 5's landscape, war is also god. Territory, violence and religion are interlocked, as if they were the everlasting paradigms of the American landscape. Perhaps this is why the series turned so readily back to its so-called "home". Here was the perfect epitome of Far Cry's colonialist attitudes, need for violence and worship of landscape. Here was the first frontier of America, the one whose structures of oppression and war would be carried further afield. Far Cry is at home in Montana not because it is the origin point of the series, but because it is the origin point of its values. Here is the landscape in which its violence was born, among tall pines and a famously "big" sky. It is part of Far Cry's path of self-discovery as a series, as it drags its colonial baggage from one landscape to the next, never able to escape the ghosts of war. As the Judge puts it: "all games aspire to the condition of war for here that which is wagered swallows up game, player, all."