The deleted scenes of Doom

Exploring the game that could have been, and the legacy that never was.

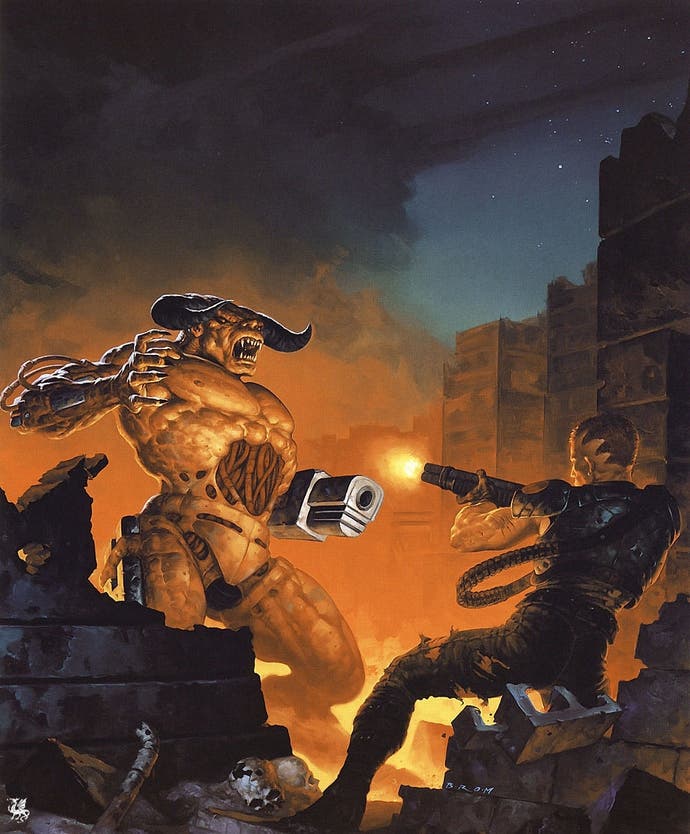

There are few games that will ever have as much impact on the games industry as Doom. Two decades after release it remains a touchstone for the genre, and has influenced a whole generation of designers; the shooter that defined a thousand shooters.

For all that impact and import though, Doom is nothing like it was initially intended to be. Tom Hall's original design document suggests a wholly different game than the one eventually released - a game that may have left behind a far greater legacy had it ever been achieved.

"Doom takes up to four players through a futuristic world," explains Hall's summary. "They may cooperate or compete to push back the invading hordes... [and] the environment is one big world, just like real life."

Continuing, the design document sketches an outline of a game that's closer to Left 4 Dead than the actual Doom - a co-op romp through a realistic military base filled with undead and devoid of lava traps or acid pits. There was even a proper story too; one set to span six episodes and with a far deeper narrative than Id had ever tried before - or arguably since.

"You are a soldier in the UAAF (United Aerospace Armed Forces) assigned to the military research base on the darkside of the giant moon Tei Tenga," reads a draft press release - and already there are significant differences. In the finished game the UAAF is changed to the UAC and, while the name Tei Tenga still appears on computer readouts, Doom is actually set on Mars' moons.

"You and four friends are having a game of cards in the hangar bay," Hall writes, describing the opening cut-scene Doom never had. "Meanwhile, the research team are doing experiments at the anomalies found on the moon. There is a flash of horrible light and two gates open at equidistant points on the moon's surface... Every awake [sic] is quickly killed. One reaching for the alarm button has his hand chopped off!"

Granted, the occasionally broken English doesn't do the proposed storyline any favours - especially when characters have names such as Janella Sabando and Petro Pietrovich - but it's better than nothing. Between the episode-by-episode summaries and the brief character bios there's enough to provide a flavour of the Doom-that-might-have-been. Think Left 4 Dead meets System Shock.

Regardless of the greater plot movements, it's Hall's narrative design that really illustrates how different the game was supposed to be. The finished Doom has players progressing linearly and searching for identical, single-use keycards, but Hall wanted more context for items and areas that had recognisable uses.

A cut area called The Officer's Club, for example, is described in the design document as a private bar where players could find "a neat collector's pistol (if we can have weapon quality)". There was no other purpose for the area - the Club was an optional stopping off point for those who wanted to explore and who'd collected a dismembered hand that could fool the biometric locks.

The game was still linear, of course. The overall goal was to rescue your friend, Buddy Dacote, from a pair of demon twins who inexplicably hold him hostage - but there was plenty to do on the way and players were encouraged to deviate from the main path. There wasn't much of a rush because behind the scenes Buddy's fate was already sealed - his terrible surname stood for 'Dies At Conclusion Of This Episode'.

While Hall's design document lays out Doom - or Doom: Evil Unleashed, as it was known then - as a four-player cooperative shooter in an open world, little of that vision was ever realised. Instead, Hall left the company due to creative differences before Doom was finished and the game was refocused in his absence.

This gradual slide away from Hall's outline is evidenced through Doom's four pre-release prototypes too. Starting with a barebones technical demo and ending with a press-only beta two months ahead of launch, these act as a playable timeline. John Romero may have suggested in a GDC postmortem that Doom was developed without much pre-production, but the prototypes suggest there was more refinement than he lets on.

Take the level designs, for example. Hall's original plot called for Doom to focus on realistic, utilitarian buildings, but the prototypes quickly move towards more fantastical layouts. This came from the team's discovery that believable locations weren't that fun to fight in, leading them to focus more on the sprawling and trap-filled designs made by Romero and other designers.

"Tom made a bunch of levels that were basically cement blocks," Romero said in his post-mortem discussion at GDC 2011. "They weren't that fun to go into; they were corridors with rooms. [They] might have made sense...but flow-wise [they were] no fun."

Ultimately that sense of flow became a far greater priority for Doom than maintaining Hall's narrative and, as a result, even the smallest attempts at environmental storytelling were sidelined. Doom had been intended to start in the hangar where the heroes played cards, a short cut-scene ending with players standing around the card table and even holding in their inventory the sandwiches they had been eating.

The finished version, on the other hand, retains the title ('Hangar') but nothing else. There's no cut-scene, no clue as to why players are there and no explanation for the acid pits that litter the area. The card table doesn't show up until the second chapter (Level Seven, 'The Spawning Vats') and is left unexplained even then. The sandwiches are long gone, too.

Not all of Hall's ideas were discarded - teleporters and flying enemies remain, though he had to fight hard for their inclusion - but the story and co-op were sacrificed very early. The first tech demo features a placeholder HUD that devotes space to inventory and co-op communication, but two months later the first alpha had neither.

It's a shame, obviously. After leaving Id Software Hall revisited some of his ideas (and character names) in Apogee's Rise of the Triad, but that's still more of a bastard son than a true heir. The game that Doom could have been and the alternate legacy it could have birthed are both long since vanished - though Hall isn't as bitter as you might think. Instead, he says that while these sorts of culls are tough, they're a natural side-effect of cramming a creative process into a development schedule.

"In one sense you need to cut what doesn't fit," Hall told us. "It's the excrement filter that refines the purity of what the game is. It's called killing your darlings [and] that's great. The other sense is painful. What you envisioned does fit perfectly, you just don't have time to do it. That happened on Anacronox - there was a perfect, awesome larger story and we had to cut it in half to finish the game. That is painful."

"Having a creative job is really great," he concludes. "It's also mental torture."