The Cosmic Wheel Sisterhood review - dealing a powerful hand

Charm in spades.

The first and only time I had a tarot reading was at one of the lowest points in my life, on the cusp of serious decisions where there didn't seem to be any tolerable solution. It wasn't a serious reading – my friend Veronica had a deck and a basic understanding of tarot, and we sat around her dining table on a quiet afternoon in Los Angeles, trying to make some mystical sense of my situation while laughing. As someone used to making snap decisions with clarity and (usually some) objectivity, I came away feeling a little disappointed, but curious; I'd always been interested in the idea of tarot as a narrative tool, but never found the time to learn. For the first time since then, in my first hour into the Cosmic Wheel Sisterhood, I found myself once again confronted with the known unknowns of divination. When I did my first card reading in the game, it almost felt like learning a new language.

The game's protagonist Fortuna is a gifted oracle witch, exiled to a tiny asteroid for a thousand years without her tarot deck – an extraordinarily harsh punishment from the leader of her coven. After two hundred years of isolation, Fortuna understandably gets desperate – she summons Ábramar, a forbidden cosmic entity, and makes an even more forbidden pact with him to alleviate her sentence. With Ábramar's help, she starts creating a new not-tarot divination deck to rebuild her craft and identity, and a path back to her coven. Through various chapters, the player learns about Fortuna's past, her ascension to witchhood, and the circumstances surrounding her exile, culminating in a dramatic final act of judgment.

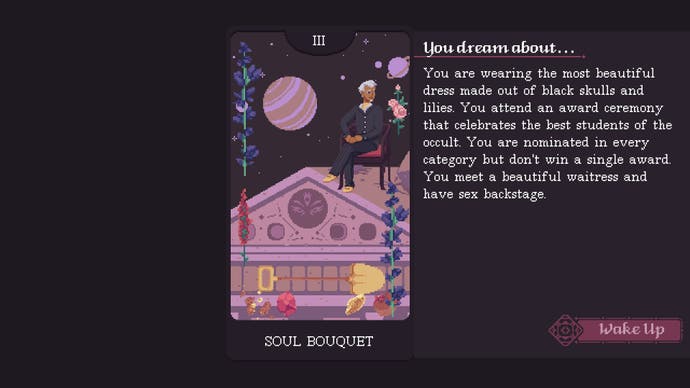

Mechanically, it's a story-driven deck builder with a creative twist: Fortuna makes her own cards rather than drawing from a preset deck. Between visual novel-style dialogue sequences, she sits at a crafting table to determine (to an extent) the meaning of each card, and how it looks by manipulating the size and placement of its graphics. Each card has three components – the sphere (background), the arcane (main icon) and symbols (minor embellishments). Each component requires energy from the four elements of air, water, earth, and fire, which in turn affect the themes and emotions each card represents. For instance, combining an earthy sphere with earthy symbols produces a rather unbalanced card full of immobility and stagnation; a fire-and-fire card brims with overwhelming transformative power. The readings themselves are straightforward. Visitors come with problems, and Fortuna draws a single card for each of their queries, which can involve a bit of internal angst when the card turns out to be anything less than a glowing promise of success and serenity.

One of Cosmic Wheel's main themes is the cyclical nature of time and events, with some characters hoping against all odds that the worst impulses of witchkind won't show themselves in the same ugly ways. The most powerful embodiment of this cautious optimism is Fortuna's fragile relationship with Ábramar – they're not the first witch and Behemoth to work together, and won't be the last, and the game does a really effective job at bonding these two pariahs with potent chemistry and sharp humor. It's easy to relate to how their pact presents an opportunity for both Fortuna and Ábramar to break the cycle and cautiously dare to be optimistic in the face of unknowable intergalactic entropy; there's a real current of anticipation and thrill that comes when Fortuna is prickly and abrasive, as befits her illicit departure from the loneliness of exile.

On the other hand, the navel-gazing about personal agency and responsibility – especially given Fortuna's burden as a witch and seer – can get a little repetitive. Cosmic Wheel tries to paint a portrait of a complex sisterhood that occasionally feels like a beginner's Plato's Republic that examines how the coven should best be governed, with mixed results. On this particular point, it was surprisingly difficult to extricate Fortuna's journey of self-actualization from my recent viewing of Greta Gerwig's Barbie, a project dressed in the right shades of girl power, but armed with baby teeth and baby ideas.

Like Barbie, Cosmic Wheel deals in the language of womanhood and empowerment – the old chestnut about how a whole, like Barbieland or a coven, is greater than the sum of its parts. Cosmic Wheel does a far superior job at getting silly and suitably edgy with its writing and characterization. Both Fortuna and Barbie are isolated from their sisters and forced through a desperate gauntlet of decisions to rediscover themselves while also ideally improving the lot of every woman around them. But at several points during the witch election campaign chapter, I found myself inevitably thinking of the Barbieland constitution finale; the latter was a withering final act that merely went through the motions of playing at politics and community self-actualization, coupled with the anodyne outcome of Barbie's personal growth. The conflict between individual and group is a simple philosophical trope that both stories dilute for their respective audiences, and I can't help but feel that both should have taken more risks in weaving in radical ideas of socialization and political organization.

Ultimately, both are blessed special girls who can walk away from it all; Fortuna, though, is infinitely more relatable if only because she's allowed to be an absolute dick, even if that means throwing everyone else under a big cosmic bus. But even when Cosmic Wheel leans on tried-and-true cliches like pitting big angry ladies against small quiet girls for dramatic effect, it has more room to paint a much more nuanced picture of womanhood than Gerwig's billion-dollar movie. This whole endeavor also left me thinking about how it's impossible to tell a good story, or really any story about womanhood, without trying to please everyone; perhaps what we really need is more universal stories about all women or all witches that please absolutely no one.

All of this messy introspection is obvious catnip for tarot enthusiasts, leveraging the well-established overlap in how tarot can be used as a generative storytelling tool in game design. The game really requires a wholehearted understanding that card-reading is a malleable, interpretive exercise, and over time I started putting a lot more care into both dialogue and card-crafting options, especially given the weight of Fortuna's power. This intense emotional resonance is the game's biggest and most understated success – there are some lovely moments of intimacy, especially when Fortuna is doing a reading for a character who wants quick and easy answers (no, they won't get any).

Cosmic Wheel's biggest triumph, though, was as a companion and means of creating meaning for me during a period of intense and sudden grief; poring over my deck and deliberating the design of new cards felt like a pleasantly warm balm. Perhaps due to the way tarot is perceived as a mystic art to glean clarity – at least to a layperson with no practical experience of it beyond corny stereotypes and that one dippy friend who visits House of Intuition too much – my approach to Fortuna's problems began to seep over into my current state of mind. Even when I didn't fully understand the card readings, I had no choice but to confront the reality of each card I drew. Over time, I got a little better at what I was doing, and as my confidence grew, so did my vision for Fortuna, and how she should position herself in relation to the coven. Each card was a challenge, but also a promise that something would happen to push the world forward; that whatever was weighing me down now wouldn't last forever. Change is inevitable, after all, and we can't hide from entropy forever. When I needed it most, the game reminded me that even if the cards didn't hold a perfect future, it wasn't the end of the world, or even the universe.