Spelunky's Derek Yu talks crafting UFO 50 and creating an entirely fictional developer

"It's a bit overwhelming."

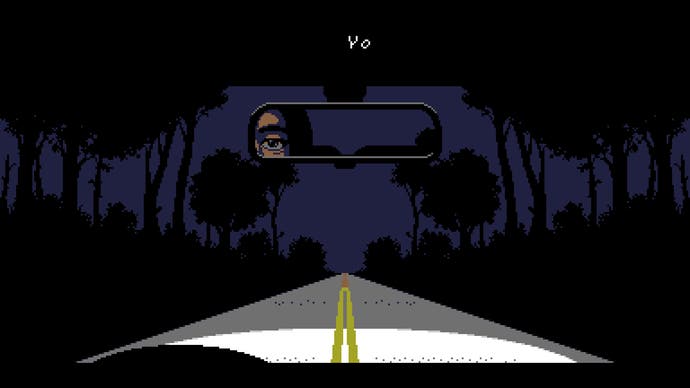

If I had to pin this impossible, improbable thing down, I would tell you that UFO 50 is a game about memory. Or it's a game collection about memory, anyway, as it contains 50 of the things. It's about the memories of what games used to be like in the 8-bit era when a lot of us were kids, but it's also about what it was like to encounter games back then. Maybe you borrowed a bunch of carts from a friend and they picked a few at random. Maybe you found one in a store on sale and it didn't have its instruction manual or box anymore. Maybe you did a Blockbusters haul one Friday and came home with six or seven unknowns to play through and discover.

And, speaking to Derek Yu, the person behind Spelunky, and the creator, along with a handful of collaborators, of the games in UFO 50, it sounds like it all began with memories too. "It really started with me and my old friend Jon Perry wanting to make another video game together after many years," Yu tells me when we chat. "As kids, we released some freeware games as 'Blackeye Software'. Our final game, Eternal Daughter, took a couple of years to finish, but otherwise they were smaller games that took maybe a month of development at most."

Yu and Perry used Klik & Play, a fairly legendary game creation tool, to make their games, and it was the launch that both of them needed to get into development. Perry moved from video games to card games, so when they were thinking of working together again, Yu suggested his friend make some prototypes in GameMaker to get a feel for it once more. "But it occurred to me," Yu says. "If he's going to be making some small games, something we both enjoyed doing as Blackeye Software, why not just keep doing that? The only trouble with that idea was that it's not easy to sell small games now and our freeware days were pretty much over." That's how UFO 50's collection concept came about - a big game made of small games. Although, granted, Yu prefers not to call the games small. "Some of them are pretty sizable!"

UFO 50 is a fascinating thing, but it's surprisingly daunting at first. Faced with all these games unlocked from the off, I personally found myself frozen for a few seconds wondering where to start. Over time, I ended up feeling that this was the perfect way to approach the collection, but I have wondered if Yu and his colleagues ever thought of leading people into it differently?

"It is a bit overwhelming," Yu laughs. "But we like to think of the Library as a place - it's like a map to explore and how you make your way through it is part of your unique experience with UFO 50. That's always been part of the core experience for us, so we never considered, for example, making you unlock games as you play." (Asked if he has an ideal starting game, incidentally, he says that he still has no idea where people should start.)

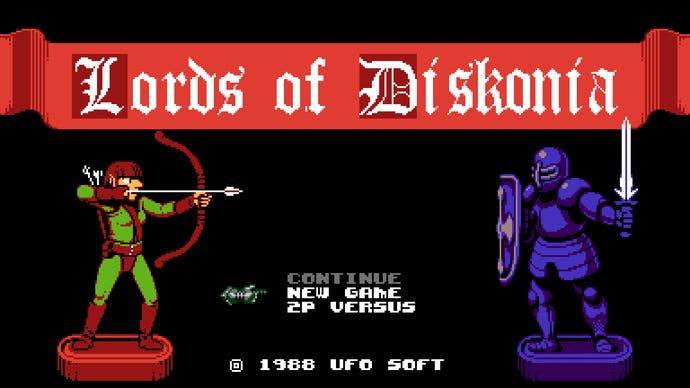

To give players a little orientation, UFO 50 comes with a fake backstory of sorts. These are all games made by a publisher called UFO Soft, for its 8-bit console the LX. In the library you can pick through the games in the fictional order in which they were released, and even read fake historical notes about each game.

"We decided very early on that there would be a fictional developer and console behind the games," Yu explains. "It's not only a great way to connect all the games together but in designing the console, we came up with certain restrictions, like our color palette, that we used to guide us in the creative process. From there, it was a matter of keeping our eyes open for opportunities to massage the games into the roles that made the most sense for them."

As an example, Barbuta, an incredibly challenging RPG and exploration game, wasn't designed to be the first game in the chronology, but as the collection developed, the team realised that it fit that role best. It's a familiar genre, after all, but still an oddity for the 8-bit era. It feels properly ancient, even down to the hum you hear when you move screens, and it's filled with secrets, too, clueing UFO 50 players into the need to approach things with an eye out for surprises.

Speaking of surprises, one of the things I truly love about UFO 50 is that the collection gives me the sort of games I would never have bought individually. This may sound like snark, but it's actually the greatest privilege - to get a game it turns out I love, but which I never would have encountered if it had been up to me. I ask Yu if there was a point where the team realised that part of the value of the collection might be freeing people from their own tastes.

"Oh, for sure," he says. "We always thought this collection was a great way to introduce people to games they might not think they'd be interested in. We're also hoping we can show people there are different ways to approach games. As a designer these days you're always conscious of the fact that many players expect to sit down at a game and just convert their time into progress until a game is finished and they can move on to the next one. But there are many games that work best as something to come back to regularly over a longer period of time - years, even."

Yu and co have found that the collection framework naturally encourages players to approach games in different ways. "You can have your current favorite you're invested in, and at the same time have other games you're hopping into now and then when you feel like it," he says. "And then there's that game you really bounced off of initially but the fact it's always sitting there gives you the opportunity to try it again when the time is right and learn to appreciate it."

Inevitably, with 50 games to be made, UFO 50 had a protracted development. I ask Yu if there were any games that sort of got away from them during development. Did any games that started small turn big, and did any totally transform over time?

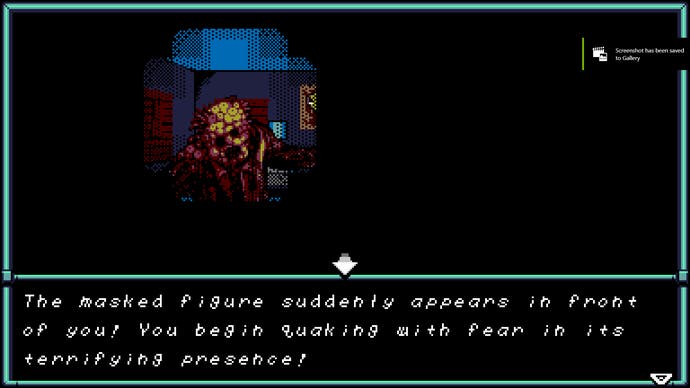

"Jon is an accomplished tabletop game designer and really enjoys multiplayer games," Yu says. "So some of his games, like Rail Heist, started out as multiplayer concepts but ended up with single-player modes that were quite different to play. And I was directing a cyberpunk RPG that was eventually replaced with Magic Garden, of all things. It just felt like we had one too many RPGs, both from a variety standpoint and a workload standpoint, and with Magic Garden I wanted to add an arcade game to the collection that offered that satisfying feeling of clearing the screen, but in a unique way."

The Magic Garden point is interesting. To work as a collection, UFO 50 must be surprising, but it must also be balanced. I've wondered while playing how much thought went into getting that balance just the way the developers wanted. Did they ever find themselves making a game because the collection just needed that specific genre?

"Each game needed to have its own unique identity but it also needed to be part of the collection," Yu explains. "I would say that most games started as their own thing, though, and then became more and more considerate of their role in the collection as time went on. And through that process, each game's identity actually became stronger because of its connection to the whole. It didn't just exist in a vacuum anymore - a game could be a sequel or share themes with other games or maybe be something one-of-a-kind. There's a lot more context for each game as part of UFO 50 than as a standalone title."

Before we sign off, Yu admits that his personal favourite game in UFO 50 changes with his mood. "But I do find myself returning regularly to Party House to look for a few more silly synergies between the guests," he says. "That game and Pingolf are two titles that I love popping into whenever I get the chance.

"But right now I'm actually enjoying playing through Grimstone again - I'm finding that the steady pace of an RPG is really comforting during the always hectic days leading to a game launch."