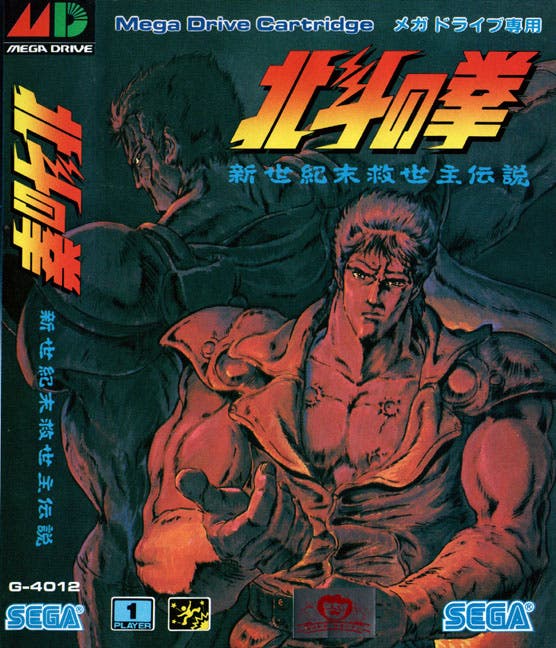

Shin Seikimatsu Ky¨ąseishu Densetsu Hokuto no Ken retrospective

Atatatatatatatatatata!

Hokuto no Ken - or Fist of the North Star as it's known in the West - is Japan's Mad Max 2 derivative; a vision of primal brutality, god-like power, and teeth-rattling violence. Taking on a life of its own since its 1983 genesis, it's outlived its influences by a considerable margin.

Kenshiro, the man with seven scars, is a wandering enigmatic executioner; a pillar of cross-hatched muscle that dishes out retribution by way of Hokuto Shinken, a martial art that ruptures internal organs by striking the body's acupressure points.

Hokuto no Ken has appeared on several video game platforms, but rarely capitalises on the rich legacy of the manga or Toei Animation's fierce TV series. One would assume writer Buronson and illustrator Tetsuo Hara's undemanding and malleable material - a concept revolving around men with tree trunk arms bleeding machismo and beating the hell out of even larger enemies in post-apocalyptic cities and biker occupied wastelands - would be right at home as video game material. Sadly, even though Yuji Naka's Master System attempt was a better early effort, it wasn't until Arc System's superb 2005 fighting game that justice was duly served.

The Mega Drive adaptation courtesy of Sega is a direct sequel to the Master System game, picking up the manga's story arc after the death of Kenshiro's nemesis, Raoh. One aspect it safely carried over from the source material is that it's hard as nails.

Crowing on about established greats is way less fun than slinging rotten food at failures, but before bucking the retrospective trend by focussing on a less than significant gaming experience, it's worth noting that there are some good aspects to Sega's exasperating licence.

As will be alien to anyone who encountered the western localisation, Last Battle, which went under the censor's knife and was completely rewritten, the Japanese release retains the series raw violence: bodies exploding in fountains of blood, internal combustion, and all sorts of rupturing.

Taking place in the wastelands, the game is governed by an overhead map plotted with stages spread across multiple paths. You can make one map movement at a time, visiting or revisiting levels, with most sections acting as filler of sorts; pass-throughs where you mash the heads off a slew of incoming attackers in desolate towns. Each kill builds a power meter at the foot of the display that eventually prompts Kenshiro to rip through his jacket and level-up. In this bare-chested state his punches and kicks are rapid and his health more resilient, allowing you to challenge the chapter boss, inch his energy down, and fulfil the requirement of finishing him with a punch - at which point Kenshiro launches into his notorious Hokuto Hyakuretsu-ken (Hundred Crack Fist) gala.

It's a workable system ruined by a thankless process of trial and error. The aim is to strategically figure out the best level order for building your strength, but the only way to know what a stage has in store is by entering it. If you unwittingly head directly to one of several mid-bosses before you get enough on the power meter, you get pulverised - and the chapter guardian is totally off-limits until you've dealt with all the preceding sections.

Boss fight claustrophobia - giving you mere seconds to hurriedly wobble in and trade hits in an attempt to squeeze a victory - would be less disconcerting if you had more than one opportunity to practice an encounter before being whisked back to the title screen. Unfortunately some bright spark on the development team decided to give you one life and no continues to finish the entire game. So taxing is the requirement, that should you play it for several years, restarting enough times to make incremental progress and learn the entire game by rote - as well as being blessed with some god-given luck - you'll probably become Kenshiro: full-bearded, shadowy eyed, and talking in whispers about killing things. Sadly you'd also be certifiably insane, and likely still short an end sequence.

Learning to clear the first chapter is perfectly doable, after which you're demoted back to a fully clothed state and instantly butchered by a new boss. You then hit start and repeat the motions, most likely to be killed again. Consult a tutorial and you can put a winning strategy into practice with no guarantee you can get it to work first time, meaning more potential restarts until you nail it. Claw a victory and you can be sure that it in one or two stages you'll be going all the way back to the beginning under similar circumstances. This wouldn't be such a Crack Fist in the jewels if the campaign weren't so inordinately long and repetitive for a single-life format, its hour plus play time grinding the very soul out of you.

The graphics are early Mega Drive average, demonstrating several special shades of sand and concrete - but they're in context, at least. The sprites are bold, but like the backgrounds they're recycled constantly, with a few palette swaps and tile switches later on, and barely any frames of animation. Bosses occasionally look the part, but their joints are so frozen it's tough to discern any kind of rhythm or cue for attack.

The music is dire; a handful of uninspired plodding themes that are lazily remixed throughout, and structural variety is non-existent; the same single-plane punch and kick action occasionally broken up by maze-like warehouses loaded with projectiles. You do get to cross the sea on a boat and beat up a pirate, and thankfully at just over halfway your power meter hits maximum and you stay in beefy Ken mode permanently - but there's precious little in the way of variety.

Hokuto no Ken's few good ideas are sadly buckled by abnormal brutality, stiff controls and cheap collision detection. Countering flying axes and incoming objects is tricky, and jumping is a science, particularly on bosses who like to throw things at you in ceaseless, unintuitive patterns.

Challenge is a preferable trait, and one sorely lacking in today's gaming landscape - but there are sensible boundaries. No second chances is astronomically daft in a game that suffers from static controls, undodgeable attacks, and limited breathing space. For an early Mega Drive release there was potential in Hokuto no Ken's atmosphere and incremental power-up system, but ridiculously underdeveloped boss fights and absolute zero tolerance for failure will eventually end your good intentions with a shirt-bursting cry of "Sod this!", an evacuation of the cartridge from the slot, and a swift explosion of plastic and semi-conductors against the nearest wall.

Not to worry though - it was already dead.