Rich Stanton on: From Billions to Bedrooms

Life in the sausage factory.

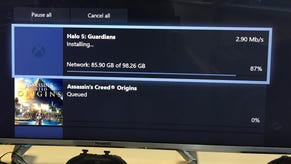

It took my Xbox One more than a day to download Halo 5 on an extremely fast connection: the power of the cloud, eh? It felt like I was back on the Dreamcast. But let's be honest, slow downloads are the least of Xbox One's problems: last week I read an article headlined 'The Xbox One is Garbage and the Future is Bulls***.' While I don't agree, it was hard to read about mandatory installs, updates, and other tiresome minutiae without some empathy. We've all been there and, in the grip of frustration, many of us react by letting rip like this.

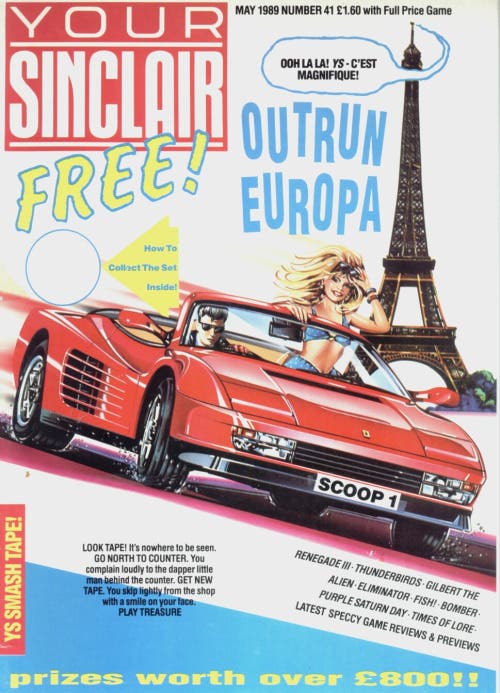

With Halo 5 the only appropriate response ended up being humour. It's not that this stuff doesn't bother me, so much as I'm always aware of where we've come from - and when people say the good old days were better, it's hard to take as anything other than nostalgia. My introduction to gaming was a machine that often refused to load games at all. That barnacled beauty, the Spectrum 48K with separate tape-loading deck, opened mine eyes to the light - and when you spend your first few years thinking that video games take ten minutes to load, and some never will, seeing a cartridge in operation is like seeing the future.

In the early 80s, gaming in the UK meant more or less the various models of Spectrum, BBC Micro, and the Commodore 64. Two of these were homegrown machines, while the Commodore 64 was designed in America - which made the UK a unique marketplace. It was a brief but bright era, and one that saw many of today's global luminaries get their start. The Master System and NES did alright, but it wasn't until the 1990s that the Mega Drive and SNES started attracting away the video game-curious public and, in most cases, the best British development talent.

The recently-released documentary From Bedrooms to Billions, available on Netflix, tells many stories from this era in the UK games industry - and through piecing these together, a big one. I've previously spent some time researching this period so already knew many of the players, even a few of the anecdotes, but over a chunky running time the film builds up so many experiences - some told at the time, some decades later - it captures a little bit of what the air must have smelled like.

Obviously there are great personal success stories, and it's great to see the likes of David Braben, Ian Livingstone and the Stamper brothers well-represented. But what makes Bedrooms to Billions a great documentary is that while it lives up to the title, it also uses it to spend a lot of time on the reverse. The film's directors, Anthony & Nicola Caulfield, never shy away from the fact that not all creators were so fairly-rewarded, or capable of dealing with success.

It is heartbreaking to see Matthew Smith, the creator of Manic Miner and Jet Set Willy, struggle to speak clearly about a time that is clearly a source of bad memories. Smith was a whizkid coder, who not only made great games but filled them with idiosyncratic touches, but the context hints that the pressure of making Jet Set Willy led to some kind of emotional trauma. Smith himself, in a 2005 interview, described that time as "seven shades of hell." He completed Jet Set Willy, and it was the #1 selling title in the UK for months after release. Both of his games were huge hits. But Matthew Smith doesn't look too rich.

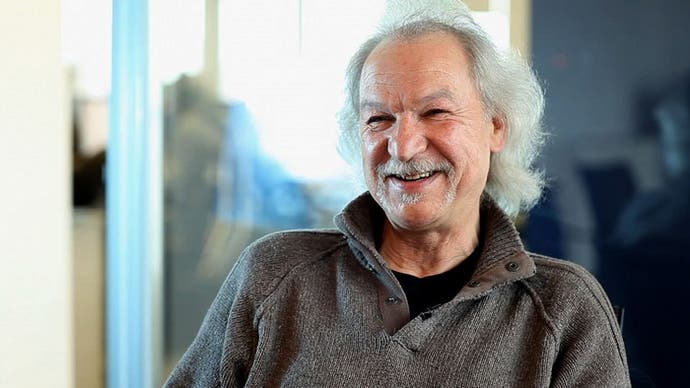

"By 1984, certainly 1985, the parasites had moved in" says Mel Croucher in the film, miming Pac-Man munching with his hands. "Yeah. The managers, the agents, the celebrity agents, accountants, the bankers, the lawyers, the publicity agents. The parasites had invaded, because they could see the body was ripe... for bloodsucking!"

You don't need to agree with Croucher's perspective to recognise he's pinpointing exactly what drove the change from Bedrooms to Billions. Croucher was behind Deus Ex Machina, a cross-media Spectrum title of serious ambition that rubbed the fledgling medium up against traditional forms - and used the latter to offset obvious technical weaknesses, like sound. Deus Ex Machina's commercial failure is widely attributed to the cost, which had to cover two tapes (one game, one soundtrack), a poster and an elaborate gatefold sleeve. Retailers refused to stock it. Croucher embodies the contradiction of wanting to make something artistically pure for a commercial market, a tension that will be a theme in video games for as long as they exist.

Coming down too hard on one side or the other is foolish, because no-one can downplay the importance of paying your rent. The 'bedrooms' label was accurate in the Spectrum's first years, but the machine's success soon led to a hunger for software. Some developers got away with murder, selling barely-functional ripoffs of popular arcade games to an audience they'd never see. But overall the potential sales started to drive quality up, as companies began competing to make bona-fide hits, and it's where the bedrooms begin to disappear because - outside of remarkable solo acts like Jeff Minter - the people making the games are increasingly full-time employees.

Which in turn meant they were now working for companies that needed to keep the hits coming in an unpredictable market. The possible consequences of which were, amazingly, recorded by a BBC documentary crew sent to film Imagine Software in 1984 for a series called Commercial Breaks. Imagine was one of the breakout success stories of the era, only founded in 1982 but quickly establishing itself as a hit factory with the then-stunning Arcadia and a series of well-made shoot-em-ups and arcadey titles. The BBC documentary plays up the fast cars, the millions in turnover, and the ambition.

The latter was what Imagine called 'Megagames,' titles that would sell at a premium and look and play better than anything then in existence. The first two, Psyclapse and Bandersnatch, were advertised but never released. When the documentary crew arrived to film what they thought was a high-tech success story, they captured the last days of Imagine Software - bailiffs, unpaid creditors, and the hollow-eyed finance director.

Even thirty years on it's awful to watch the foot soldiers, almost uncomprehending, as the company implodes around their ears. The film crew spends some time with a sales rep, who tries to interest a major distributor in a game she can't show them that will cost £40 when the average price is £6. It's hopeless. You see the founders desperately scrabbling for anything that might save the company. Eventually you see the employees being locked out forcibly by the bailiffs, their bags and jackets lost. Even before the film crew leaves, Imagine is finished bar the shouting.

The history of our industry is not just a list of the successes. It is also a history of colossal failures, shuttered studios, and in some cases outright criminality (here's looking at you Fat Steve.) It is the history of a new and enormously powerful creative medium being colonised by money, and alongside that is the human element - the mass of people swirling around and actually making the things.

Which is why knowing about failure matters, and why Bedrooms to Billions is a great documentary. The successes always speak for themselves, but this gives a voice to those who did alright and those who just got burned. While so much of the 80s British software scene may be irrelevant to today's global industry, that cliff-face of failure is not. At the top end it's even worse, thanks to today's giganto-budgets and the committee-led products they result in, while among independent developers there's a new hard luck story every week.

This is a thread in games history: how badly the creators often get it. Since there's been a commercial software market, publishers have fought against giving too much credit - or job security - to the people who make them. Electronic Arts was explicitly founded to re-address this imbalance by treating developers as artists, would you believe.

The sharp end of the industry often treats people badly, and nor do the employees themselves do much about it. Among the many reactions to the video game voice actors' strike, I was amazed to see some prominent developers slightly confused by the role of the actors' union. Many further opined that the request for percentages was ridiculous, which is even more amazing: don't coders and artists and the hundred other creative roles realise that they should be collectively pushing for this stuff too? Video games is a multi-billion dollar industry that depends entirely - entirely - on what the creatives produce. It's incredible that the Independent Game Developers Association, a world-class clown school, is the most well-known representation developers have.

The games industry is cyclical and, every so often, that means you see bodies in the road. Another ongoing theme linked to this is the gold rush. In Bedrooms to Billions you catch glimpses of the adverts that enticed young coders to send their games to publishers in the hope of riches. And you see people who got ripped off, too. A more insidious heir to this kind of activity are today's courses offering to teach 'how to become a game developer.' Young dreamers always attract the bloodsuckers.

Steven Bailey, a former journalist and now industry analyst, recently wrote about his disappointment with Tony Hawk's Pro Skater 5 - and his inability to be venomous about it in the way he may have once been. It's not a simple call to be 'nice,' so much as an acknowledgement that sometimes the people most disappointed in a game are its makers.

Once you have that sense of how the sausage is made, it's hard not to be aware of what can be in there. The metaphor is forever fixed in my mind because David Doak (who makes a welcome appearance in FBTB) used it when talking about how Free Radical, the great studio he co-founded, had been messed around and eventually thrown under the bus by publishers. I adored Free Radical's games, and my first assignment as a journalist was to visit their Nottingham studio. Hearing about what was really going on at that time, years later, awoke me irreversibly to the human cost.

Bedrooms to Billions and the BBC documentary give us a glimpse of the production lines. But it's something to bear in mind for balance, not as an all-encompassing truth. The games industry is not a terrible hellhole of parasites and darkness. The opposite is broadly true. It is a place where enormous achievements and rewards are possible, built around a medium that has potential beyond any other in existence.

So as I observed my Xbox One downloading Halo 5 like dial-up was back in fashion, I gradually became amused rather than angry. I saw it was a common problem, lots of people were complaining about the same thing. I saw all the tweets aimed at Xbox support, or 343 Industries, or Phil Spencer. And I realised that, of all the people in all the world, the ones that were probably the most upset about this were the ones being blamed for it.

Amazingly, I felt bad for Microsoft. Who knows where the fault lies? The technical explanation is probably so boring we'd fall asleep while hearing it. But I'll bet it's nothing to do with the Xbox support people, or Halo 5's developers, or even the company's top suit - even if he'll have to take responsibility. So much venom raining down on the wrong targets.

At the time of writing, Halo 5 has just finished downloading: it took almost exactly 24 hours. A day is a long time, but I don't mind - it's a feeling I remember from the 80s. One of the first gaming lessons I learned, perhaps the first, was when my mother would demand I turn that thing off and play outside, or get to bed. Games might be everything. But sometimes you need to think about the wider world, switch off, and play tomorrow instead.