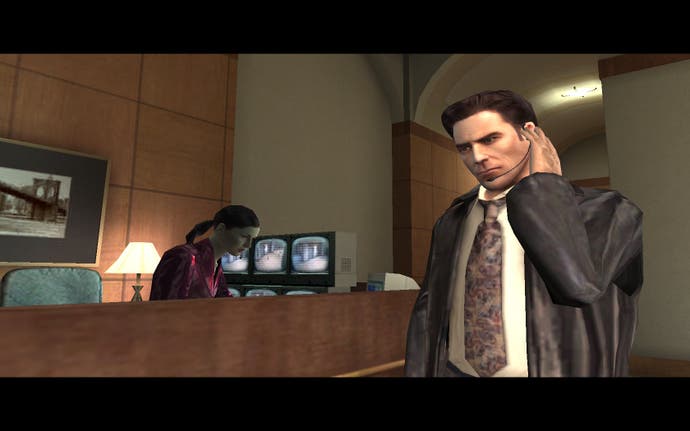

Retrospective: Max Payne 2

Let the bodies hit the floor. (Sometimes the ceiling).

When someone says they're not excited about Max Payne 3 my automatic reaction is to screw up my eyes and give them a hard stare. The statement, and often its calm delivery, destabilises me. Who is this person? Why do they have this wrong level of excitement? The balance nubbins in my ears revolve gently while I'm derailed onto a track several degrees asynchronous from reality. Max is the dearest of all my friends. How can he not be yours?

Perhaps it's a PC thing. Max's heyday was certainly seen in with mouse rather than gamepad, so it's entirely possible that he's more fondly remembered in the Keyboard Kingdom. Or maybe it's a symptom of both Payne games being instigators of great movements in gaming, rather than the classics that continued or ended them with a flourish. After all, the only thing our disgraced cop hero ever really ended with a flourish were the lives of gangsters hit by two taps from his sawn-off - in which case Max would tend to pirouette his body round a full 360 degrees while reloading.

At the time of release both games delivered instant hits of novel gameplay that, as other developers caught up, wouldn't remain novel for very long. The first Max Payne saw the beast of bullet-time slouching towards Brooklyn to be born, while the sequel was one of the earliest outings for fully-fledged physics and cartwheeling ragdoll bodies.

Max Payne 2 was a game in love with gravity - willing go to any length to make things twist, tilt and fall over. Shoot your first crim in the opening hospital scenes, for example, and he'd dramatically collapse into hospital shelves (shelves!) while the camera gently span. In the year 2003 jaws were summarily dropped: a replay in 2012 reframes it as pantomime over-emphasis. The sheer amount of flying street furniture now becomes a third person shooter variation on over-enthusiastic writers getting hot and heavy with multiple exclamation marks.

Max Payne really isn't the only one doing the falling here. Wherever you roam there are bits of wood balanced on barrels that just happen to jut out into your path. Where there are explosive barrels, there are stacked tins of paint. When a man tumbles from a building, he does so onto an unlikely and unsteady outcrop of scaffolding and wooden planks. Much later you'll find a room with a fragile ceiling, its only occupants being an explosive crate upon which one enterprising criminal has balanced ten plastic chairs, four tyres and a bucket. It doesn't take a pyrotechnician to work out what happens next...

In this day and age the splayed legs, the flying bodies and the choral cries of "Get him!" don't make for a refined blend but, god damn, I still love it. It's a Valkyr shot that's kept me coming back year after year. I've probably completed the game six or seven times now - with replays of my favourite levels precariously balancing many tens of hours on top. My fanaticism however, doesn't just stem from its idiosyncratic mannerisms and narration (excellently, and tenderly, skewered by John Walker in his previous retro piece on the original game) that worked so well here - but would go on to add a little too much 'OMG, drama!' to renowned self-obsessive Alan Wake. (A shared acquaintance of Remedy's scenery-gnawing twosome is surely the MS Word mantra of 'Fragment. Consider revising.')

No, what brought me back time after time was an undying sensation of pure, mindless and kinetic violence. It's by and large a fanaticism that first came about on the discovery that iTunes would comfortably run behind the scenes - letting me choreograph my own personal action scenes to a playlist of angry rock or (if I was feeling a little bit philosophical) baleful plinky-plonk schmindie-indie.

There is nothing, it turns out, more cathartic than lifting the body of an evil cleaner up and against a wall with sequential slow-mo bullets at the exact point of climax in Limp Bizkit's Break Stuff. Likewise, listening to the Mad World cover from Donnie Darko and lolling your head in time to the arse-cheeks of a cartwheeling Mona Sax before she obliterates two goons (and a stepladder) with dual-uzis really makes you think about life... and stuff... you know?

My primary reason for writing this Max love-in then (aside from dramatically revealing that my musical taste hasn't developed by one iota in ten years) is simply to address the crowd of people I've discovered who are steadfastly refusing to recognise Max Payne 3 as the most exciting game of the year. (Potentially ever!!!). There are plenty of 'gamier-than-thou' types just itching to inform that Payne's third outing looks like nothing more than running around and shooting. My answer to that is simply: when did awesome running around and awesome shooting stop being awesome? It didn't. The clue's in the over-use of the word 'awesome'.

It's true that this looks to be the first Max Payne game that's sat on a bandwagon rather than leading it. It's also true that 'Fat Max'™ doesn't worry my shrivelled, spluttering adrenal glands as much as he perhaps should. Payne remains, however, one of the greatest and most under-appreciated gaming heroes of all time: part pastiche, part serious and part (grudgingly) self-knowing.

His world is also a fantastic and unique collision of noir desperation and Captain Baseball-bat Boy irreverence. There is no level in gaming as special or unique as the 2D drawings writ large in Mona's Reality Springs funhouse - whether it's on fire, or you're simply there to wander through its halls and wonder just what the hell is going on. Likewise Max Payne and Max Payne 2's fascination with dreams, and their student philosopher approach to the nature of reality, give the series an ethereal spin unmatched elsewhere.

To me, Max Payne is a bastion of quality - pure and simple. You wouldn't necessarily trust him with looking after your kids - there's a chequered record on that count - but at the same time you'd know that (after a breakfast of whisky and painkillers) he'd find the time to avenge your inevitable death. After all, everyone Max knows generally perishes.

Above everything else, however, the utter joy to be found in Max Payne is simply through picking up the guns of bad guys, and then feeling compelled to give them back. One bullet at a time.