Remembering Iain Banks: a prolific, terrific talent

Culture cachet.

There is a well-worn story about the late Iain Banks and his relationship to video games. In the 1990s, the puckish, prolific Scottish author - who cheerfully hopscotched between publishing mainstream literary best-sellers as Iain Banks and science fiction novels as Iain M Banks - became so addicted to Sid Meier's Civilization that it threatened to short-circuit his writing career. Ultimately, he deleted the game from his hard drive in order to resist temptation. But the spirit of Civ - and other games - clearly bled into his work.

In Banks' bleak 1993 whodunnit Complicity, a speed-dabbing journalist juggles deadlines and sleuthing to maximise the hours he can pour into empire-building PC sim Despot, a "stunningly Machiavellian turbo-screamer of a game". In a novel not short on gut-punch moments, a particularly sneaky one arrives when the stressed hack gets his confiscated laptop back from the cops. Some plod has unwittingly left the Despot campaign running, and with no guiding hand on the trackpad our rumpled hero's once-thriving civilisation is ruined and beyond repair. (The book's capable killer also takes time out from staging baroque murders to share a nifty cheat for an aerial combat sim entitled Xerium that involves surfing the shockwave of a nuclear explosion.)

In 1996's Excession, the fourth of Banks's sci-fi novels set in the symbiotic human/machine intergalactic utopia of the Culture, artificial intelligence clever-clogs known as Minds entertain themselves by experimenting with the options sliders on virgin galaxies to analyse the pinballing ways in which they might evolve. This God Mode mucking about is interrupted when an inscrutable but all-powerful on sphere appears on the edge of Culture space. In interviews at the time Banks likened that plot development to the stomach-dropping sensation in Civilization of seeing a fleet of AI-controlled ironclad warships on the horizon when your fledgling society has barely mastered clay pots and raffia mats.

More games: Banks's 2007 family saga The Steep Approach to Garbadale revolves around an eccentric clan living off the proceeds of a perennially popular, none-more-British boardgame called Empire! which - dwindling UK geopolitical influence metaphor alert - is about to be sold off to a US consortium. And an earlier Culture novel, 1988's The Player of Games, sees a listless grandmaster voyage to a far-flung alien empire where a breathtakingly complex, all-encompassing tournament comes with a suitably epic battle royale prize: becoming Actual Emperor.

That's just a taste. There should have, could have, would have been more. Banks died aged 59 in June 2013, only two months after announcing he had late stage gall bladder cancer. Ten long years without a new book from him seems illogical, bizarre. After his rug-pulling debut The Wasp Factory brought him early notoriety in 1984, Banks averaged roughly a novel a year for almost three decades. Though he clearly relished switching up his approach to genre, consistent elements of his often swashbuckling style - notably caustic wit, a weakness for wordplay and unwavering socialist politics - made the annual ritual of catching up with the new Banks feel like an ongoing conversation. I miss it. I miss him.

For a while, it looked like his name and reputation were going to be hijacked by absurdly wealthy, self-regarding tech doofuses. In his pre-X days, Musk claimed to be taking inspiration from Banks's sci-fi visions, declaring himself a "utopian anarchist" while gesturing vaguely toward the Culture universe. Amazon big cheese Jeff Bezos also publicly declared himself to be a Banks fan in 2018 when Prime Video unveiled plans to turn sprawling galactic doorstop Consider Phlebas - the first Culture novel, published in 1987 - into a live-action streaming series. That adaptation was quietly cancelled in 2020 . (My hot tip? Secure the rights to 1990's Use of Weapons, the most badass/emotionally shattering Culture book, and do it as kinetic, stylised anime: a real Machiavellian turbo-screamer!)

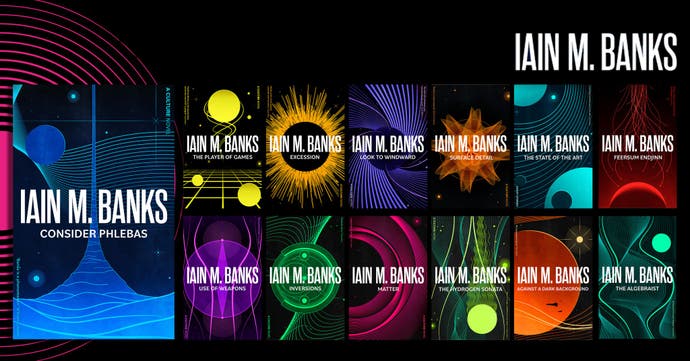

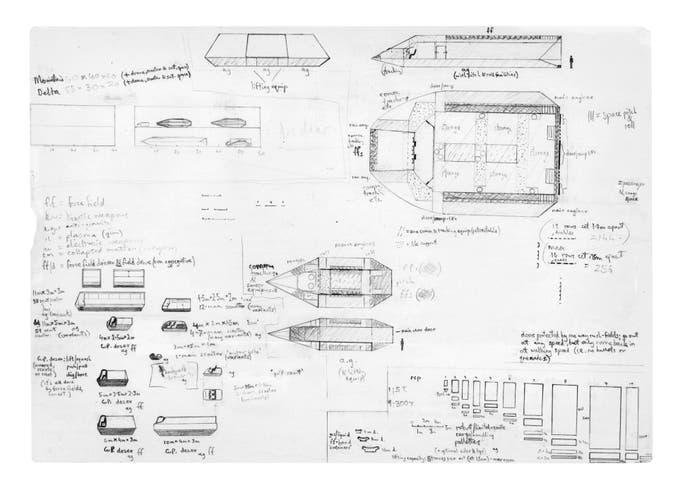

A little more than ten years after his death, we are experiencing a timely, double-pronged Banks bump. His 13 sci-fi books as Iain M Banks are being reissued this month with eye-catching new cover art - I'm getting cool synthwave vibes, but also maybe a bit of Tarot? - that will hopefully get them into the hands and brainpans of a new generation of readers. Even more exciting: the recent publication of behind-the-curtain coffee table tome The Culture: The Drawings, collating his earliest conceptual designs for what would become his signature sci-fi creation. Banks was apparently a habitual scribbler and doodler, conjuring crude but detailed geographical maps, architectural drafts, spaceship designs, weapons prototypes and the sketched-out foundations for an entire glyph-based language. (That last requires you to rotate the landscape-orientated art book 90 degrees to puzzle over Banks's exploratory stabs at nonary encoding.)

The result is a chaotic intergalactic blueprint - the Culture in skunkworks form - self-annotated in cramped chickenscratch. Banks was a dude who loved his whisky and his amateur draftsmanship has some of the character of cask spirit: raw and unrefined but heady and intoxicating. It occasionally reads like graffiti scrawled in the margins of a runaway imagination: Banksy Woz Ere. An extended chapter cataloguing increasingly ginormous Culture spacecraft sees old-school Elite-style wireframe models paired with astonishingly detailed tables of their dimensions, crew complements and capabilities. It seems obsessive and perhaps a little redundant, the sort of crammed, maniac dream journal an art department intern might be required to produce while working on a grim serial killer movie. But then you catch another dashed-off Note To Self: "Nothing is so obvious that you might not have to explain it to somebody sometime." The details matter.

One of the inspiring things about Banks was how much he seemed to enjoy demystifying the creative process. If his books were populated with occasional flights of poetic fancy, he rarely romanticised his approach to the craft. To have maintained his impressive workrate you gotta have a system, and Banks would happily talk about how he would spend six months or so vaguely planning his next book before dutifully knuckling down during the dark days of the Scottish winter to actually write it. Nine-to-five, five days a week: proper traditional working hours, if only for three months or so. But the rest of the year? Whisky. Music. Fast cars (although he ditched his Porsches in 2006 ). Curry. Poetry. Video games. Life!

Back in 2003, I got the chance to interview Banks while he was promoting what would turn out to be his only non-fiction book. Raw Spirit: In Search of the Perfect Dram was a shaggy travelogue where he drove around Scotland visiting various distilleries (this was still in the Porsche period). The obvious angle seemed to be chatting to him over a malt whisky tasting. A lunchtime session was arranged at a swanky private member's club in Glasgow. It was a dream gig. Meeting an artist I had idolised since high school. Someone who had opened my mind to what a writer could be. A tangible, relatable inspiration. Also: free whisky.

Banks arrived a little late and sheepishly confessed to be ruinously hungover. After commuting from his home outside Edinburgh the day before he had caught up with some old friends for what turned out to be a prolonged session. The premium malts in chunky crystal tumblers remained untouched. But he still provided me with reams of rollicking but self-deprecating quotes. So I never officially got to have a drink with him. But 20 years on from that encounter - and a decade after his passing - I want to raise a glass all the same. Cheers for everything, Iain.

The Culture: The Drawings by Iain M Banks (published by Orbit) is out now; the 13 reissued Iain M Banks books will be available from 30 November.