Rare and the rise and fall of Kinect

Cancelled games, Xbox 180s and Kinect Sports - the story of a revolution that didn't quite take off.

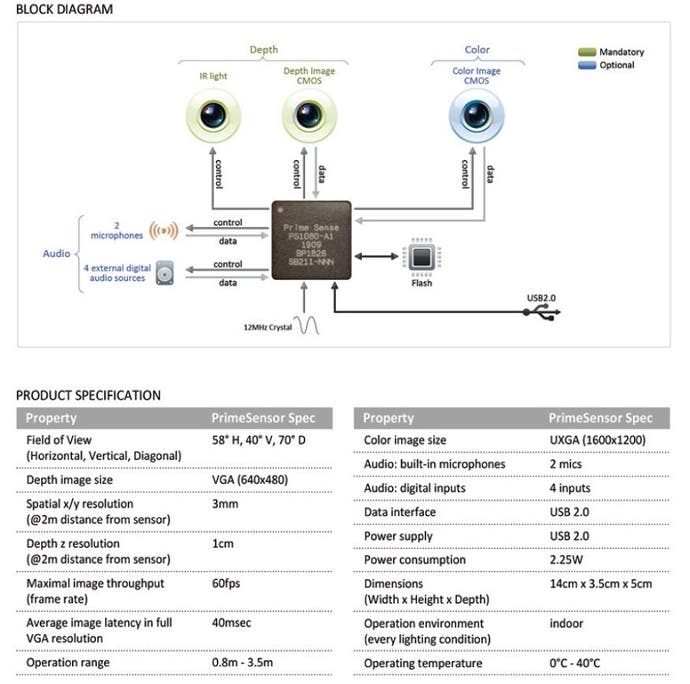

In 2009, Kinect was poised to take over the world. A witches' brew of infra-red projection, an RGB camera and a multiple array mic designed to support full 3D motion and voice control, it was the magical piece of hardware that opened video games up to everybody, by making everybody a video game peripheral.

The sensor's original codename, "Project Natal", is both a reference to project incubator Alex Kipman's native burg, and a statement of intent: this was to be a new birth for an artform long hamstrung - or so it was maintained - by the need to master an abstract input mechanism before you could enjoy yourself. "The vast majority of people are just too intimidated to pick up a videogame controller," Steven Spielberg said during a conference cameo at E3 2009, adding that "the only way to bring interactive entertainment to everybody is to make it invisible."

Looking back five years on from Kinect's eventual release, it all seems so quaint. Demand for controller-based experiences is unabated, and touchscreens rather than motion or voice controls have arguably given us the most convincing tech-led design innovations, thanks to the meteoric rise of smartphones and tablets. Kinect, meanwhile, has proven to be anything but "invisible" in practice.

The original sensor's hang-ups were many, with latency a particularly annoying bugbear, and its successor is still temperamental enough that relatively few players make consistent use of it - as Microsoft has tacitly conceded by removing gesture inputs from Xbox One's UI.

If Kinect isn't the "revolution" we were promised, however, its early success and just as sudden decline have been thrilling to behold: a tale of commercial and creative ambition scuttled by inattention to practicalities, of hubris and inertia elevated to a kind of apocalyptic cinema by the PR misfires of an industry juggernaut. As Shelley might have written, were he alive today and an awful, awful poet: "Raise hand to make a selection, ye mighty, and despair."

But what was it like to witness the saga from the inside? To find out, I spent time with two developers who were involved with Kinect from the beginning, from the feverish days of Project Natal's announcement, right through that record-breaking first year, to the disasters of the Xbox One era.

Open sesame

Among my earliest memories of Kinect in action is the sight of a Cirque du Soleil dancer mugging his way through a clash with Darth Vader during E3 2010 - a proposition to exceed the wildest hallucinations of any card-carrying nerd, for all the clunky scripting. One of Chris Sutherland's earliest memories, meanwhile, is of a mysterious locked door, deep in the heart of Rare Ltd's Twycross HQ in Leicestershire, UK.

"Rare had been going at the time from super-secretive to a slightly more open company," says Sutherland, a 25-year veteran of the studio, who is now project director at Playtonic, the youthful outfit behind record-breaking Banjo Kazooie homage Yooka Laylee. "But that was still happening when Kinect appeared on the scene. It was such a sensitive project. When it started out, the only thing I knew about it was that there was a room with all the windows blacked out. Something was happening in there!"

As the weeks went by, small groups of Rare staff were invited to see prototypes of Microsoft's new motion-control technology in action. "I can't quite place the year," Sutherland continues, "But it was a number of years before Kinect as it's now known came to be. I remember being shown a depth-sensing camera, very similar to Kinect, but it didn't have any of the skeleton recognition, so it didn't recognise you as a humanoid with limbs.

"It had depth perception, like with radar - a depth image, so you could see yourself as a figure, but the game didn't understand you as a figure. You were just a blob. We were shown that tech and asked if we could make something out of this, and I think the conclusion from folks at Rare was that maybe it was too early."

Ex-Rare designer and current Playtonic studio director Gavin Price was also treated to a demonstration. "One of the demos was quite a simple boxing game, the other was a brick wall where you could push out individual bricks, a bit like a game of Jenga," he recalls. "And we all left that meeting wondering what kinds of games we could try." There was, Price goes on, no sense at this stage that Kinect, a peripheral now inextricable from Microsoft's conceit of an always-online entertainment hub, would be for anything other than gaming. "It was definitely about games. Everyone asked the designers to go away and think up different ideas for this device."

First forays

It wasn't until early 2009, shortly before Project Natal hit the stage at E3, that Kinect's capabilities had solidified enough for game development to proceed. "The studio had just completed its restructure at that point," says Price. "We'd just shipped Viva Pinata: Trouble In Paradise and Banjo: Nuts 'n' Bolts, and I remember some new projects were prototyped after those two releases, but everything kind of got pushed to one side. We were told that the studio would focus on the Xbox Live Avatars business, Kinect Sports, and a kind of Kinect health and fitness game, I think it was."

Kinect Sports was originally conceived as a more complex sim, Sports Star, built around the idea of being a pro athlete, with gesture controls that were supposedly beyond anything available on the Wii. "But I remember at some point, the feedback came down from Don Mattrick I believe, and it was: 'No, just give us Wii Sports with Kinect.' So internally, yeah, Kinect was very much a reaction to the Wii's success, the fact that they sold millions and millions and always sold out every Christmas."

Also shelved as Microsoft moved ahead with Kinect was a prototype motion-sensitive remote, comparable to the Wiimote (and Sony's then-unreleased PlayStation Move controller) - the manufacturer had filed a patent for a 'Magic Wand' with biometric sensors in 2007. "That was something we'd been working with the platform team on," Price comments. "But the advent of Kinect pushed that out to one side. They said 'we can't have two motion tracking solutions for games - we have to bet on one of them." There were projects in development for the wand, says Sutherland, though he stops short of specifics.

Such casualties notwithstanding, Rare's teams were enthusiastic about the idea of a peripheral that was designed to render analog sticks and buttons obsolete. "When development of Kinect Sports began it was a blank slate," says Price. "Lots of different prototypes were in play, prototypes based around UI and menu selection - what that would involve in a controller-less world. I remember a spinning globe with different options on different sections of its surface.

"We tried lots of different sports, because I think the original plan was to do more than six sports in Kinect Sports. Some of the prototypes were instantly really good fun - I don't know why we didn't go ahead with those. We had cricket up and running, an earlier version of table tennis, rock-climbing... I saw a flying minigame where you flapped your arms."

The more Rare got to grips with Kinect, however, the more it became conscious of the sensor's limitations. "We were literally putting kitchen foil from supermarkets over windows, to get the best lighting conditions possible. It was an exciting time because it was all new, and everyone wanted to be the next one figuring something cool out. But it was also a really frustrating, pull-your-hair-out time.

"Nothing was happening on screen, and you were like 'Is it me? Is it the camera? Is it the lighting in this room? Am I wearing the wrong clothes?' It was failing. And it wasn't like you were pressing a button on a pad and nothing was happening - you just didn't know what was going wrong. It was really frustrating early on."

The problem wasn't merely that the recognition itself had faults. An elementary difficulty with Kinect's grand premise of the body as "controller" is that bodies aren't assembled on a factory line. "'Everyone's the controller!' Well, everyone does things slightly differently," explains Price. "Even something as simple as somebody just holding a hand up - some players would hold it at shoulder height, but maybe the device had been programmed to look for a hand above shoulder height."

The Wii isn't quite as prey to the vagaries of user behaviour because it still uses a controller with predictable inputs - buttons, a trigger, gyrometers and the option of an analog stick. With Kinect, Rare was obliged to spend long hours at the testing lab, gradually working out which inputs required the least explanation. "You didn't want to make any particular person feel like they couldn't follow an instruction that simple," Price goes on. "So you were constantly redefining every single action, and hoping that it would give you the best end result across a wide range of users."

"We had so many different forms of the text that said 'raise hand to start'," recalls Sutherland. "We had 'lift your hand above your head' - but then some people would place their hands over their heads as if they were about to pat it."

The road to launch

While developers were wrestling with Kinect's quirks, key aspects of the hardware were still taking shape. Rare worried "constantly" throughout the creation of Kinect Sports about how the sensor would perform in different living spaces, says Price. "The hardware team would say: 'Don't worry, I know you're having to play in a room with tinfoil over the windows'. Were they going to pack tinfoil with every unit sold? 'No, no, we're improving it over time.'"

"And a lot of things did improve over time," notes Sutherland. "It was just difficult to know which." The first promotional videos of Kinect set player expectations unhelpfully high, wowing viewers with the prospect of fully motion-captured real-time kung-fu duels, and a racing sim a family can play from the sofa, with a second player serving as your pit crew. The Kinect Sports team were aghast. "Everybody thought 'oh, that's what it's going to be like!'" says Price. "And we were looking at it, thinking: 'Is it? Is it really?'"

One of Microsoft's more significant decisions was to drop a built-in processor that would have handled skeletal mapping, obliging Kinect to draw on Xbox 360's CPU instead. This lowered the cost of production, but also ate into performance, torpedoing more aspirational motion-controlled projects such as Capcom and From Software's Steel Battalion: Heavy Armor years in advance. "When we heard the microprocessor wasn't coming, so that all input would still have that lag, I guess it was an opportunity for the software guys to think even harder about how we get ahead of [the recognition]," says Price. "There was a lot of predictive work going into it. 'Well, we think the player's doing this action, even before they've done it.'"

Sutherland likens the stresses of launching alongside Kinect itself to that of developing for a new console. "And on top of that, you were launching a new way of interacting with games, of interacting with a machine in a way nobody had done before." The exhilaration of release was invigorating, however, with Microsoft blowing $500 million on a marketing campaign that included giveaways on the Oprah Winfrey show and a celebrity dance event in New York's Times Square. Kinect Sports proved to be one of the system's strongest titles, rivalled only by Dance Central from Rock Band developer Harmonix.

The new peripheral went on to set a Guinness World Record, selling eight million units in its first 60 days; by February 2013, there were 24 million Kinects in the wild. It was an enormous hit, helping to bring about an unprecedented year-on-year increase in sales of Xbox 360 hardware, and a correspondingly huge influence on the direction of Microsoft's third Xbox console, which was coming together slowly in the shadows.

But the figures are a little deceptive, with Xbox 360 bundles accounting for a significant percentage of Kinects sold, and Kinect games a tellingly infrequent sight in the charts. As early as December 2010, analysts such as Pacific Crest's Evan Wilson were expressing concerns about the performance of Kinect software. Recognition issues, the fundamental ambiguities of motion control and the lure of traditional fare like Call of Duty: Black Ops ensured that for many players, the device was little more than a Christmas party gimmick.

"Everybody had their first Kinect experience and said: 'This is great, but now I want to get back to the storyline or the action or whatever it is'," observes Dan Thomas of software company Moov2, organiser of the Kinecthack development jam events in London. "Maybe the biggest barrier is the friction of having to clear your room, to make space, when really you just want to get into your comfortable routine of sitting at your desk or on your sofa."

A shortage of distinctive, original games for Kinect didn't help. Too many of its best titles were, and are, robust elaborations of concepts pioneered by the Wii, and more involved or innovative experiences such as Lionhead's nigh-mythical Milo & Kate or Rise of Nightmares either failed to materialise or proved too demanding for the technology.

Microsoft's attempts to cross-breed Kinect with existing IPs, meanwhile, provoked fiery reactions from returning fans. 2012's Fable: The Journey was particularly derided. "People see that and they think a core Fable game hasn't been made, because they've diverted resources towards this instead," notes Price. "It's kind of an attack on your culture, on your beliefs. It's like with that Metroid game they announced recently at E3 2015. People said, 'That's not a Metroid game - if you're doing a Metroid game, do a bloody Metroid game, not that thing.' Kinect caused that very same reaction."

"Generally things don't cement themselves until they're in the hands of the creators, and in this instance they put it out there, made it available, and yeah the ideas, the implementations didn't surface," says Thomas. "The creators couldn't think of them. Microsoft didn't think of them. I certainly haven't! I definitely think that the lack of killer content was a problem."

The honeymoon period

In the immediate aftermath of launch, however, everything was rosy. Rare's success with Kinect Sports put it at the forefront of Kinect development, and other teams were eager to tap into its expertise. "Everybody was sharing a lot of information with the Kinect team and other developers," says Price. "It was a very friendly time. Everybody was passing on hints and tips on how best to get the hardware to do what you wanted it to.

"I remember moving onto Kinect Sports 2 - the golf side-on stance, we shared that information with EA for their Tiger Woods game. They wanted to know how we were getting such good data back from a person standing side-on when typically Kinect looks for a skeleton face-on - how we were getting good tracking results. I think we were sent a few free copies for helping out. Microsoft needed as many developers as possible on board and yeah, Rare was central to lots of those conversations."

Ideas for brand new games were thrown around internally, but Rare's management and Microsoft elected to double-down on the emerging Kinect Sports series instead. "I think because we'd not made a massive hit for Microsoft like we had before they bought us, people at Rare and Microsoft saw this as a chance for Rare to do something big and own an audience, a key part of Microsoft's business. But the result was we couldn't work on the kinds of game we'd traditionally worked on, because there was such pressure to deliver a fantastic Kinect game, to inspire other developers.

"To remove all risk we knocked all of the teams on the head, and everyone kind of chipped in and joined the Kinect Sports team. I think that was the biggest team we've ever had on a title in Rare's history, and Kinect Sports: Season Two eclipsed that, even taking into account the fact that Big Park helped on two of the sports for Season Two."

Among the shelved projects were a number of Kinect titles, ranging from the Kinect equivalent of Wii Fit to a few quirky originals. "I was working on an adventure-style game where you explore a haunted house, using Grabbed By The Ghoulies background assets," Price continues. "We had junction points, you could select new routes, and you'd come across physical puzzles. It was the Kinect equivalent of the Professor Layton series, where instead of mental puzzles you'd complete challenges which would require all sorts of bodily movements.

"One was that you could see your character standing in a pit of rats, and one rat had the key to the exit, so you were trying to stamp on all these rats and get the one with the key. Another was throwing bombs at gargoyles - until you'd got rid of them, you couldn't cross this drawbridge. Lots of things like that. It didn't go very far."

Another abandoned project saw designers transforming an old boardroom into a life-sized boardgame to test the concept. "You'd stand up and roll dice to move to different themed areas, travel all around the world. You'd land in Italy and I think there was a minigame where you were holding a pizza, and you'd try to catch ingredients as they fell. There were quiz questions and you'd stand on a 'true' or 'false' square to answer. It was kind of like a Mario Party game for Kinect. We built a beach - there would have been hula dancing, I think, or maybe that was me just turning up to work one day in a hula skirt."

Xbox One's Kinect

As development continued on follow-ups to Kinect Sports, Rare was also being shown early versions of the technology that would comprise Xbox One's Kinect sensor. "They had a toy pirate ship they held up to the new camera, and you could see it replicated quite well in Kinect's scan view," says Price. "It had a wider field of view, and could track you at longer distances. Mostly it was an improvement on everything that came from before."

Many of the activities ultimately supported by 2014's Kinect Sports Rivals were designed to show off the new sensor's capabilities. Jet-skiing was an advertisement for being able to play while seated; rock-climbing was added to show that Kinect could distinguish between open and closed hands. The new sensor was a formidable overhaul, with a wider field of view to offset the removal of the original's tilt motor, but there were still gaps between the rhetoric and the reality. Rare had intended to track trigger finger movements with target shooting in Rivals, for example - in practice, the precision wasn't quite there. "With the second one it maybe got to the level of promise of the first one, technically," says Sutherland. "But by then we were promising more."

Kinect 2.0's undoing would ultimately prove, however, to be Microsoft's vision for entertainment consumption across the board, rather than any particular issue with recognition. The device had become central to Microsoft's efforts to transform Xbox into an all-singing, all-dancing delivery vector for every kind of media, backed by a futuristic UI, with video games merely part of the package.

This was a promising move for the nascent Kinect gaming scene. It meant that the new sensor would be sold alongside the console, creating a stronger economic case for Kinect exclusives. But when the dream of an all-in-One tomorrow fell over - demolished by Sony's focus on specs and gaming applications with the substantially cheaper PlayStation 4 - Kinect went down with it.

The months building up to and after release were a humiliating series of tactical reversals and blunders. Faced with a user privacy backlash in the wake of Edward Snowden's revelations about NSA snooping through connected devices, Microsoft rejigged the console's OS to function without the sensor plugged in. It then struggled to localise Kinect voice controls in time for launch, leading to a staggered roll-out across non-US territories. A couple of months after Kinect Sports Rivals hit shelves in April 2014, the publisher opted to sell a version of the machine without Kinect for the sake of price parity with the PS4. Then, it unlocked Kinect's share of GPU resources to counter Sony's specs advantage.

It was a difficult time for anybody associated with the Xbox platform, but these were especially distressing events for Rare, which had spent years reorganising itself to serve as Microsoft's premier Kinect studio. "We thought: 'Wow this is great for us - we're going to be really important,'" says Price. "And then during Rivals' development, Kinect kind of got dropped quite suddenly. I think in part it was because we missed the launch date - I don't think that did us any favours! But we managed to get a jetski demo out for Xbox One's launch, and we had our cloud-based Avatar creation system with the facial recognition as well."

Microsoft's grudging abandonment of Xbox One's online requirement and mandatory Kinect did not, he goes on, greatly affect development in a material sense. "It was more just the sudden realisation that this game which everyone could play who buys an Xbox One - maybe more people are going to buy a version of Xbox One that lacks a Kinect. And I think that's been the case since. So we kind of felt marginalised, but ultimately we had to get on and make the best game we could, because that was the right thing to do."

Rivals proved to be a decent enough follow-up, but fell a long way short of the killer app Kinect needed to justify its continued existence to players. According to a Eurogamer report in May 2014, the studio made a "significant loss" on the project, which debuted at 14th in the UK weekly all-formats sales chart, and suffered a number of layoffs. The Xbox One's fortunes, meanwhile, began to pick up as talk of UI features and entertainment applications faded, with new Head of Xbox Phil Spencer putting the spotlight firmly on games like Halo and Sunset Overdrive at E3 2014.

Kinect's decline

Among the final projects Gavin Price worked on at Rare was a whimsical "conflict-resolution game", roughly titled "Kinect-Off", in which players race to perform a random action such as 'jump, then touch the floor' while their Avatars do battle on-screen. Thrown together for laughs during a gamejam, the title was also, in its way, an earnest celebration of the second generation Kinect's finesse - unchecked, as so many Kinect games are, by the expectations of genres that have coalesced around controllers or mouse-and-keyboard. Now-departed Microsoft Studios vice-president Phil Harrison was apparently a fan.

"You could use it to show off all the things Kinect could do, that nobody had tried out at that point in time. Such as 'hold your hands exactly 18 and a half inches apart'," Price recalls. "All these things Kinect doesn't get asked to do in other games. 'Blink.' 'Blow me a kiss.' You could even use a pad alongside it, like 'press A on your controller', and the best thing to do there would be to grab your mate's controller and hurl it across the room. I remember sometimes the text would come up really small, so you'd have to get in close to read it. And the command would be 'move backwards'. It could headf**k you like that. It was really fun but alas, it's never seen the light of day."

Surprisingly, there appears to have been little interest in recreating one of Rare's proven IPs with Kinect. While they acknowledge that betting everything on Kinect Sports was a sensible decision at the time, Price and Sutherland agree that setting aside a small team to revive an old franchise - whether for Kinect or not - might have served Rare better. "I think it would have been an easier sell for Rare fans to say, 'Don't worry, the studio's doing this and servicing its old IP as well,'" comments Price. "The fact that Rare became completely aligned with Kinect took away the possibility of giving a lot of gamers something they would have immediately loved." Sutherland suggests that the game could have taken the form of a Kinect exclusive, a controller game, or a mixture of the two.

Microsoft is commonly blamed for Rare's transformation into a so-called "casual" studio, but Price feels this is a step too far. "Phil Spencer taking the mantle of Xbox is one of the best things that could have happened for Rare," he comments. "Because he's always said to people at Rare [as general manager of Microsoft Studios], 'Do what you want to do and we'll back you,' and he's always stayed true to his word in that regard. It was people in Rare's management at the time who said: 'Well, Kinect is a great opportunity for the studio - go all in on it.' So when executives at Microsoft see that the management team are passionate about doing that, they back them. Microsoft to their credit did that, and perhaps the story online isn't quite reflective of the truth.

"Every company makes mistakes, and people forgive certain companies more than others. We all love Nintendo so much we can forgive them for whatever they do. We'll always forgive them, the day the next Zelda comes around. Everybody likes to create this narrative that Microsoft are evil, but that's not the case - they were very supportive. I guess there were a few people who have since left who thought: 'I wanted to be working on this game or my pet project, and I didn't get to.' And they've kind of painted a picture that it's all Microsoft's fault."

Moving on

At the time of writing, the future is reasonably bright for Rare. The studio's forthcoming Sea of Thieves, a pirate MMO done up in wistful, Banjo-esque art, is an attractive marriage of tropical nostalgia and cutting-edge technology, with real-time naval battles in which players must work together as a crew. Offering up a world of quintessentially platform-game palm trees and sparking cannonfire, it seems the kind of experience connoisseurs of the studio's 90s output have been clamouring for. And as for Kinect? Well, it's not all doom and gloom.

Moov2's Dan Thomas points to an array of non-commercial experiments from indie programmers and creators from other industries, ranging from art or music installations to a Kinect app that can be used to view X-ray scans during surgical procedures. Last year's Kinecthack was a testament, he says, to the peripheral's flexibility as a platform. Its highlights include a juggling trainer, a version of Pong that is played by doing push-ups, an app for people with cerebral palsy that transforms gestures into speech, and an Oculus Rift hybrid in which Kinect is used to model the player's body in a virtual world.

"There are so many parameters - depth, motion tracking, facial recognition, all of these things that it can do, and somebody could still come up with an amazing idea," enthuses Thomas. But the days of big-budget mainstream Kinect releases appear to be over, nonetheless.

We should give credit where it's due. Kinect helped revitalise the Xbox 360 as a platform midway through its life, and there's the odd headline game, such as Swery's demented and sadly underloved D4: Dark Dreams Don't Die, or Q Entertainment's sizzling laser display Child of Eden, that hints at what's achievable when you treat the sensor's eccentricities as an excuse to strike out afresh, rather than "enhancing" a proven formula with wonky gesture or voice inputs.

You could also make the argument that Microsoft's sensor helped inspire and shape the present taste for "natural user interfaces" in devices of every sort - I'm not sure we'd be quite as in love with voice commands, for example, if it weren't for Kinect. But Kinect itself was and is a mixture of novelty and frustration - a passing and peculiar fad that stands as a warning to overweening evangelists of latter-day gadgets, such as the latest virtual reality headsets. For all Rare's sacrifices, and for all the ingenuity of development teams around the globe, that door in Twycross is still locked.