Shadow of the Colossus

The bigger they come.

Shadow of the Colossus is a wonderful game.

16 giant monsters made of brick and fur, stomping around desolate environments waiting for us to find them, trick or trip them into letting their guard down, and scale them and slaughter them - I was in love with that game before I even saw it.

Giant, organic puzzles. Better: giant, organic puzzles that roam around a world designed by the people who made ICO. Even I'm slightly bored of waving ICO around like a Top Trump at playtime by now, but its presence in the back of the mind was the real shadow lurking over the colossi, promising fluid platform control, engrossingly understated characters and desolate settings, and above all that the designer was capable of directing such simplicity, such a deliberately threadbare idea, with the steadiness and concentration of a proven auteur.

So it was, somewhat ironically, that the hype ICO never had became its legacy, and in the end spoiled the experience of actually playing Shadow.

You've probably read at least one review of this game already, so I'll try and keep things simple. You're trying to revive a young girl, and you've brought her to the edge of the world, to a land stalked by giant furry brick-monsters, where you've heard that souls can be retrieved. Dormin, a disembodied voice that booms at you from the rafters of the shrine where your beloved lies dormant, instructs you to bring them down to try and achieve this. And so you do. With the help of your beautiful horse Agro and a magical sword, you navigate across the bleak, uninhabited land that surrounds you, and stalk your oversized prey.

To find it, you raise your sword aloft and rotate until, like a compass point, it directs you to the target. Onward you'll bound, navigating giant chasms, through canyons and, as you draw closer to each colossus, even over sequences of platforms and ledges in a manner not too far from the kind you'd expect in ICO - or, if you're not one of the original 25,000, those of Prince of Persia are an equally good example.

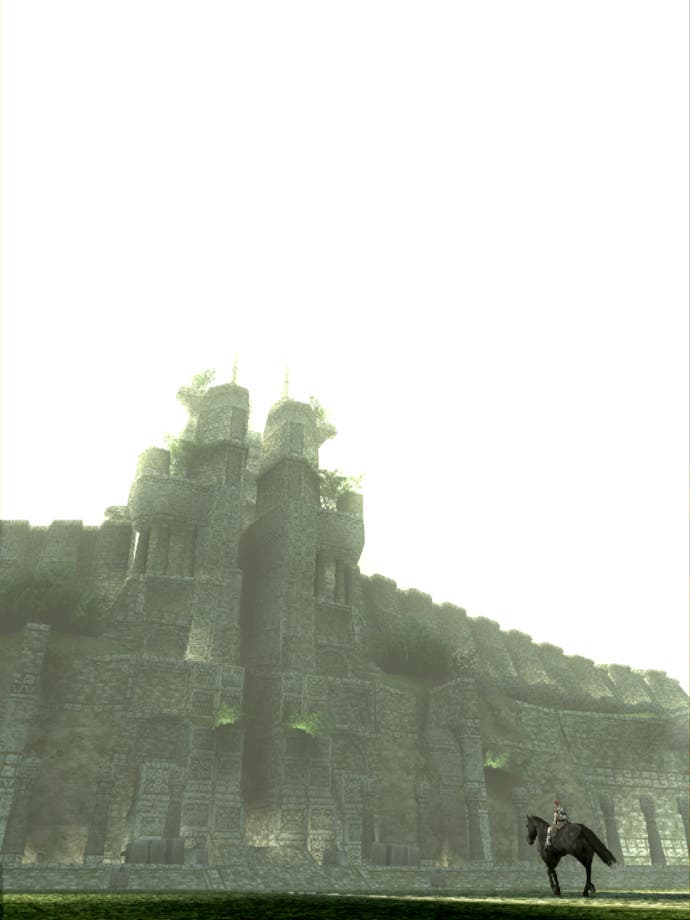

When you find what you're looking for, the game pulls back to emphasise the magnitude of the task, and the accompanying music - largely unobtrusive outside of colossal encounters - rises with the kind of choral solemnity you'd expect to encounter in a dark cathedral on the eve of judgement day; it marks this moment out as the start of a grave matter.

For you it's not though; for you it's the start of a titanic struggle. First you have to locate the giant's weak spot, and then you have to exploit it. And it's here that the game is simultaneously at its most brilliant and most frustrating - and the point at which you realise that this isn't quite what Ico told you to expect. Curse him.

Any failings outside these encounters are forgivable. Agro may frustrate you from time to time by refusing to go between a pair of trees or jump a particular gap, but he's actually a very intuitive animal, happily bounding over a narrow ridge and changing direction slightly as you spur him without the need to tug on the reins. And you may get lost on your way to the fight, but this is almost always because you went the wrong way; in a sense it's the game's fault that you got lost, but in a world where every clop of the hoof is another brick in the atmospheric wall that your isolated enemies are preparing to burst through, only the importunate critic's likely to complain, and only as deadline approaches.

What's harder to forgive is dying, or having to repeat tricky manoeuvres, because you've been literally and figuratively thrown off by the work of a cameraman in a neckbrace, or a harsh function of a merciless design.

When it works, fighting a colossus is unlike anything you've ever done in a game. Endlessly circling at first, inspiration hits you and you try something to make a breakthrough, maybe taking advantage of some quirk of the setting or some promisingly exposed patch of furry flesh in a delicate region. It's a big thrill when you first discover that your plan to put an arrow in the exposed calf of a humanoid, or unbalance a thick-skinned quadruped with a shot to the foot, is enough to put them at a temporary disadvantage. Then you climb on.

Here you discover one of the most ingenious bits of design. Once again, it's the R1 button - it held Yorda's hand in ICO, and here it holds onto the fur or ledge you're clinging to as your adversary overcomes his momentary slip and regains his stride (or canter, or even flight). How you'll cling to that R1 button. And how you'll watch that shrinking pink circle in the bottom-right corner - along with the weapon icon and the relevant health bars, one of just four bits of screen furniture - and pray that he stops bucking and twisting so you can climb higher and seek respite on surer footing. Reaching higher is about charging up a jump by holding triangle and trying to grab on further up, or by crawling painstakingly over furry flesh.

From then on, it's about finding the glowing white tattoo that marks the weak spot, and sticking your sword in it enough to kill. Which is to say, it's about holding on, struggling against Richter-scale environmental shifts, and judging how much weight you can cram into each sword strike before you have to concentrate on holding on again, and how many times you can afford to do it before your pink circle becomes nothing, and you're thrown a hundred feet or more to the ground.

Because getting back to the point of bringing the sword down is rarely something you'll want to spend time doing: given the intensity of the build-up, the satisfaction of delivering that decisive blow, and the elation you'll feel when it goes in and the music changes and it's all over, gives everything a bloodthirsty sense of urgency. It's quite a chilling effect when you think about it given the ambiguity of your situation: ICO was an innocent quest, and after a while this feels more like selfish slaughter. Hang on, you'll think, is this really right? It'll occupy your thoughts a bit as you ride to your next battle. Being given the space to think - and the genesis of significant internal debate - is one thing that ICO and Shadow both get right.

I'm getting sidetracked, but there's relevance. The problem, for me, is that when I'm riding to the next battle, I'm often cross, when I should be getting drawn into the dilemma. When I bring down a colossus, half of what I'm feeling is relief and even bitterness. Shadow is at its most brilliant when you have an idea, it works, and you succeed. The problem is that it's too harsh on you when you make a mistake, and when it makes a mistake it replaces the excitement of knowing you're right with the intense frustration of knowing something bad wasn't your fault.

When you slightly misjudge the amount of time you have left to cling onto the wingtip of a flying beast, or mistake a particular pattern of twisting and flapping for one that lasts half the time, and you fall to the water below, you might have to swim for up to two minutes to get to where you need to be; not to mention the need to re-establish your connection with said wingtip, which isn't exactly like hailing a taxi. This would be forgivable if it, and the consequence of your other minor errors, were isolated problems. As a developer, you can't always legislate against the stupidity of the thumb or the panicking mind, and there'd be no way to shortcut you back to the starting position without shattering the illusion.

But you start taking umbrage with things like this when they scale up; when you get struck down by a small, fast-moving colossus that can strike you again as you're climbing back to your feet, for example. Or when you're knocked sideways and lose half your health because you're expected to twist your bow and arrow, while on horseback, in such a way that you'll probably lose track of the aiming reticule several times over before you succeed. Never mind the fact that you initially discounted this as a strategy because, when you do it, your character's movement and your control issues suggest that you're breaking the game.

There's been debate within the ranks here about the camera, too. I think it's a bit crap. ICO's system of electing a spectacular vantage point and then letting you adjust it slightly obviously can't work in this sort of context, so what we have instead of a controllable third-person affair manipulated with the right analogue stick - and with all the associate flaws. It's quite sluggish, it feels uncomfortably tight to your character, it squirms uncertainly in tight spaces, and seems to take odd paths around objects - particularly when you're trying to twist it to see yourself on the other side of a colossal arm or beard. Being able to locate the colossus mid-picture by holding L1 makes some amends, but even this is slightly haphazard, sometimes focusing on a body part you're not interested in.

I've shouted at games I've loved before. I even shouted at ICO from time to time - there's a bit near the end with some rubbish checkpointing that accentuates perspective issues in a way that simply shouldn't have got through, and so my neighbours endured my raised voice once again. But with Shadow it's different - it's endemic. I am often angry while I play it.

In truth, it is far more satisfying to return to, and to talk about afterward, than it is to play through the first time.

Now, Rob has an alternative take on this. He contests it vehemently, arguing that sitting in a crowded room with his friends trying out strategies as people called them out was one of his favourite experiences of last year. And I can see how it might have been. But I'm not about to recommend a game because a handful of brains can make light of its challenges and negate a lot of the frustration, before conversation dulls the pain of the process. That's not good design; that's just a good house set-up and yes I'd like the spare room.

If anything, it backs up my point anyway - sharing Shadow with people is the most fun. Playing Shadow when you know what to do is fun - retracing my steps through the game this week was like watching a classic film where you know all the lines and you're watching it because the lines themselves are brilliant and hearing them again makes you happy. Some of these ideas are things I'm going to want to smile at again for years to come. And there's something so reassuring about a developer that doesn't clutter its game with procedural combat and storytelling - not because it'd make things less believable or less enjoyable, but because it'd make the game into something it isn't meant to be. Shadow of the Colossus, like ICO before it, is what Sony meant. You'll want to remember how you felt about that again, and it'll be easier next time.

Which, in a slightly loopy way, is my way of saying that Shadow of the Colossus is worth buying. Not necessarily because you'll love every second of playing it, but because when you look back on it, when you drag it out for your friends, and when your finger runs across its spine and picks it out of the shelf-stack line-up 18 months from now on a rainy weekend when your girlfriend's at her mother's, it'll be another ICO moment.

Right now though, I'd rather hold Yorda's hand again.