Rollercoaster Tycoon 3

Supa-dupa looper-troopa. IĄŻll stop.

Order yours now from Simply Games.

My Dad built the rapids ride at Alton Towers.

No, really.

Well, not by himself. But being a Brickie-cum-foreman-cum-construction worker chap, he was one of the people who performed manual tasks and hard, outdoor labour that would mentally scar lightweights like me. He also claims credit for having the water flow over red sandstone rocks to get a slight scarlet tint to the waters for the bit where the giant rubber tubes pass between two water-falls in a parting-of-the-red-seas style. His working there lead to a batch of free tickets which took the family a couple of years to exhaust, so acting as a beam of light in an otherwise dreary midlands existence. Through my youthful eyes, this was the second best job my Dad ever worked on, just ahead of constructing Stafford’s McDonalds (so bringing home bags full of Hamburglar pens) and just behind Drayton Manor Park and Zoo (from which he managed to secure a splendid polystyrene replica skull).

And difficult introductory paragraph out of the way, that Rollercoaster Tycoon 3, eh?

Championship management

It’s been a game that’s always been easy to damn with faint praise. It walked that odd line by being both a genuinely great game while also crossing over to the non-hardcore gamer market. It’s easy to view it through the filter of a proto-Sims, filling the niche of a Management game that sold millions (both of itself and add-on packs) to both gamers and people who wouldn’t normally pick up a game box. And, post-Sims, it lost some of the stigma that it had picked up among the sort of gamer who objects to games that sell to people who have no interest in whether Id’s next graphic engine will be tuned for best rendering brown or grey. Because – well – the Sims now gets that particular stigma.

Which just leaves it as a magical management game. But why does it work so well?

The concept helps, clearly. This, like the original Rollercoaster Tycoon, takes the concept of Bullfrog’s groundbreaking Theme Park and just runs with it. You have money. You have a park full of rides and other glad-making machines. By spending the money to make the park more glorious, guests will arrive and give you more money on making your park more magnificent. Compared to Theme Park, Rollercoaster Tycoon had a stroke of pure inspiration: you were actually able to design your rollercoasters in a manner which rests half-way between art and science.

Crunchy numbers

All of this remains in Rollercoaster 3, expanded hugely with the pretty-meter turned to blistering… but what, specifically, is so special about running a amusement park that racks the sales figures up so?

My theory is that – like the Sims, in fact – it comes back to the aforementioned “Art and Science” aspect. Many management games lean purely to the economic number crunching, having satisfaction based purely on managing to make a few dozen variables balance and everything to not come grinding to a halt. It’s the ordering principle of the human mind in action – the part which can’t help but shuffle a pile of papers so the edges meet. However, Rollercoaster Tycoon has an equally well developed artistic side. Some of this feeds back into the simulation – that making a beautiful park by positioning statues and other items leads to the customers being more impressed. But much of what you do is relatively irrelevant – choosing the colours of various parts of your rides, for example. That adds nothing to the game… except the glowing sense of satisfaction the creator gets when looking across their perfect creation.

When approaching Rollercoaster Tycoon 3, its developers – this is the first time Chris Sawyer has worked with a full team on one of his games – clearly understood its two poles of appeal. Both the heart and mind of the game have had close attention paid to it, and the results mostly speak for themselves.

(Well, they don’t, hence this review. I was trying one of those writerly figure of speech things I’ve been hearing so much about.)

Scream if you wanna go faster

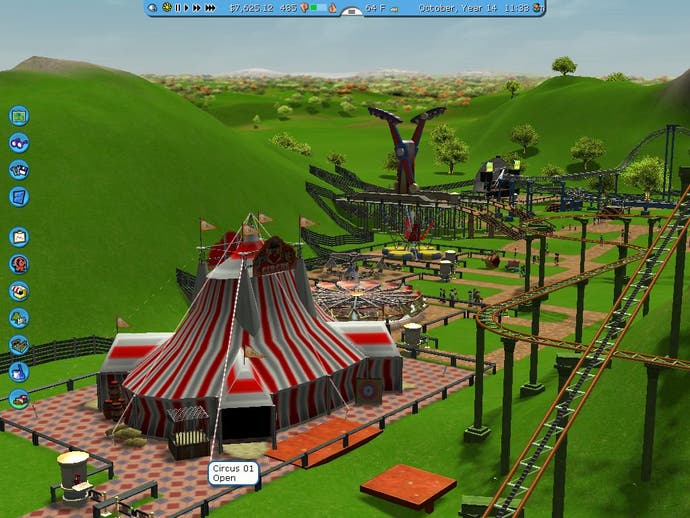

The shallower side first. And stating the obvious: Rollercoaster Tycoon 3 is as gorgeous as I’ve ever seen a management game. Crowds of thousands mill around your carefully constructed pathways. On night levels, illumination is only cast by lanterns, with your cursor surrounded by a pale nimbus of light. The fact this is a full 3D engine also allows more convincing parks to be constructed, especially with the landscape shaping tools with which you can carve the very soil itself into two enormous earthy bosoms. Er… if you want to. Others could manage some rudimentary phallus if they so desired.

The step into 3D also expands the ability to customise the game. As well as prefabricated scenery, you’re able to go into a separate designer and make something that suits your desires. Music files can be imported, and linked to individual rides – and, as long as you identify their genres, the simulation appears to respond to your DJing choices, with demographics either enjoying it or being repulsed. So if you really want to make your entire park play Belle and Sebastian records, you’ve only got yourself to blame if it fills up with skinny guys with backpacks. [Hey! I don't wear backpacks! - Belle & Sebastian loving Ed]

Also you can now climb aboard any of your rides and experience it in glorious first-person-o-vision. Now, we’ve seen similar modes before – perhaps first in Theme Park World – but it’s only now with the this generation of graphics which it really works. For this virtual-rider, there’s a genuine rush as you’re around the track, corkscrewing before plummeting down a steep slope. On the slower rides, it’s a supremely relaxing way to admire your park.

Oooh, ahh, a little bit more

But the most impressive of the aesthetic additions also crosses over into the more functional sides: the firework displays. Here, you’re able to arrange joyous pyrotechnics with a control system akin to a music sequence. That is, you have a number of tracks, each of which can have a different firework releasing at any one time. While nowhere near as deep as the coaster-design aspects, it’s an amusing and beautiful distraction, and a fine way to turn bored crowds into a giggling mob incapable of doing anything other than say “oooh” and “ahhh”.

And now we mention it, a few brief words on the coaster design – still a fascinating skill, forcing you to balance the need to excite the riders without causing so much physical stress on their forms their body snaps in two. For newcomers, expect your first few rides to be physically unbearable, until you start to master ideas like banking turns to reduce Gs, breaks to control the momentum and corkscrewing all the way around the bloody thing. It’s a little easier to get hang of than the last game, due to an improved track-laying system and a “Join End” option which tries to connect your two ends of tracks together, ideal for checking whether there is an actual solution to the mess you’ve created. You can even import your old rides from the previous game in, which will clearly be a boon for its considerable community.

Not that it’s perfect. There’s some points where you can’t actually tell whether the simulation is being terribly obscure, or whether it’s an actual bug. Moments where rides just decide to stop working – without actually being broken down – almost certainly fall into the latter category. Those which fall into the former are doubly difficult to decide upon, due to the increased difficulty of gaining information about the general mood of the visitors to your park, with no simple poll functions. It’s fairly demanding on the hardware, so a world away from the low-entrance 2D world of previous Rollercoaster Tycoons. And while the building tools are improved, they’re still far from perfect, often leading to a lot of difficult backing up when you realise its interpreted something in a way other than you wish.

As good as it gets

But despite this, it just scrapes the nine, if only for the simple reason there hasn’t been high-level management game with this level of wit, style and vision since the dear departed Mucky Foot’s Startopia. This is as good as its genre gets, and deserves recognition.

Anyway: it’s the only way I’m ever going to follow in my family’s footstep and make a splendid rapids ride. And it’s at least as good as a polystyrene skull.