Putting the magic back into magic in fantasy games

On the fantasy authors and ideas about sorcery game designers could learn from.

There are few things less surprising about most fantasy games than how they portray magic, which is a pretty depressing state of affairs given that magic is, by definition, the art of doing the impossible. The impossible, it turns out, has a fairly limited set of applications. By and large, it means hitting foes with elementally-flavoured balls of fire, turbo-charging your stats or zapping wounded allies back to fighting fitness, in accordance with a collection of tactical rule sets derived from the works of Tolkien via Dungeons and Dragons.

The flipside of this is that when somebody tries something genuinely intriguing with magic, rather than just adding a few new varieties of debuff, you really sit up and take notice. It doesn't have to be anything dramatic, though shockwaves and particle effects are always appreciated - it can be a relatively delicate matter of characterisation. Take The Witcher's Geralt of Rivia, for whom magic is the equivalent of a dagger tucked into a boot, or chainmail worn under a cloak - a little something extra for sticky encounters that sits naturally alongside his understated prowess with a sword and mastery of potions, befitting of a travelled mercenary who fights with cunning rather than force.

There's no flamboyance to Geralt's use of runes in The Witcher games - no real theatre, even after upgrades, just calm, deadly competence. In the Elder Scrolls universe, by contrast, sorcery is all pomp and spectacle. The shelves of Skyrim's umpteen libraries sag beneath the weight of treatises penned by advocates of one or other wizardly school - academic polemics as believably grandiose or petty as the actual use of magic in combat is clumsy and dissatisfying.

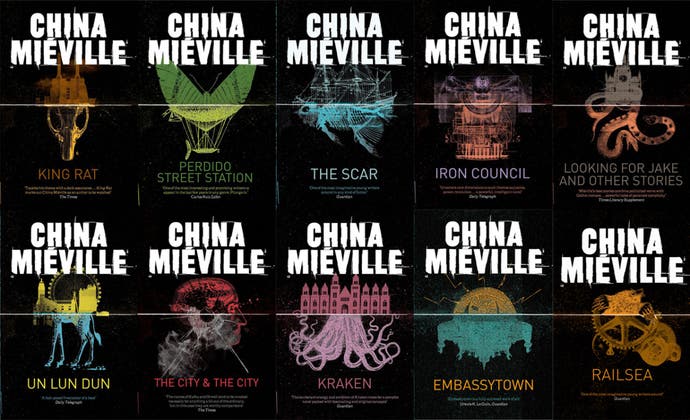

Pondering the fantasy novels and worlds I'd like to see turned into video games, I think first and foremost of the spells I'd like to wield as a player. Top of the list are those of China Mieville's Bas-Lag universe, a sort of industrialised maritime Middle-Earth in which magic, or rather "Thaumaturgy", is a mixture of fossil fuel, unproven technology and acute metaphysical malaise. This is a magic available to the stink and compromises of urban life under a nasty oligarchic regime, employed for street protests and the carrying of groceries together with the obligatory world-saving pyrotechnics of each novel's final third.

One of the first acts of sorcery in Mieville's Perdido Street Station comes when a Vodyanoi - an overgrown amphibian, basically, derived from Russian folklore by way of Dungeons & Dragons - sculpts a crude statuette from bathwater swimming with microbes and piss. Later, vodyanoi dockworkers on strike use the same species-specific talent to scoop out a picket line of empty air right across the bottom of a river. It's not exactly summoning Ifrit to polish off a Tonberry in a Final Fantasy game, but it's strangely compelling - the marvellous unleashed in the service of an unromantic workplace dispute, like picking food from your teeth with an enchanted wand.

Terry Pratchett's Discworld books have a similar sense of how magic might subsist within the tissues of a properly fleshed-out society, rather than operating as mere deus ex machina or a handy source of SFX - inter-departmental squabbling at the Unseen University in Ankh Morpork, for example, or the summoning of tiny foul-mouthed demons to paint portraits at lightspeed, in a Discworld alternative to photography. But Pratchett isn't nearly as unpleasant as Mieville, whose spellbook extends from ghastly "flesh elementals" to the existential RNG that is Torque, a form of radiation that, at one point in 2004's Iron Council, transforms a train car into a gigantic amoeba, its passengers to nuclei.

Too grotty for comfort? Ursula Le Guin's Earthsea universe is the antidote - a majestic, windy Iron Age-ish archipelago, held above the ocean by a Taoist spiritual equilibrium that's based on a healthy respect for language. Where Mieville's portrayal of sorcery revels in the horrors of linguistic alchemy - how we might warp reality by bashing words, tongues and etymologies together to fashion abominations such as the "Phasma Urbomach" (roughly translated, "city-killing spirit") - Le Guin's novels are preoccupied with the serenity that is knowing and describing things precisely as they are.

Earthsea is a realm divided into two types of language: a number of non-magical tongues that alter over the years and only reflect the surface of existence, and a draconic, abiding Old Speech that doesn't merely express the essence of a thing, but continually redefines it. To call, say, a stone a flower in the Old Speech is to force reality to self-correct, and risk plunging the entire universe into chaos.

The first Earthsea novel follows the young wizard Sparrowhawk's efforts to restore that spiritual balance by tracking down, naming and thus disarming the catastrophic result of his own ambition. I like the idea of a meditative, dialogue-driven adventure in that vein, in which a wandering mage must choose whether to use the Old Speech in dangerous situations. A game about magic, in short, in which you're encouraged to do without it, lest the island beneath your feet evaporate or sink beneath the waves. Perhaps Telltale should give it a shot.

There's a question of gender to consider here, too. In Earthsea, magic is held to be the preserve of men alone, with talented women obliged to scrape by as provincial amateurs rather than honing their craft in the famous school of Roke at the archipelago's centre. This corresponds to the old prejudice - sadly enduring in some quarters - that men are more "intellectual" creatures than women, creatures of reason rather than emotion. In a very slow playing-out of her own feminist politics, Le Guin addresses that entrenched chauvinism in the course of the series, with 2014's The Daughter of Odren delivering the final flourish.

I'm not aware of a game in which only male characters are encouraged or permitted to wield magic, but different strains of magery are used to assert worn-out gender roles in many RPGs - the demure and chaste healing priestess, versus the hirsute and commanding archmage. Developers like BioWare have done a good job of spreading the riches in recent years - whatever you think of Vivienne de Fer's dress sense, she certainly isn't there to hand out Phoenix Downs - but there's more we can learn from the stories Le Guin tells.

These fantasies also help us reconfigure what the idea of casting a spell signifies, in an industry where most forms of player interaction have come to be seen as a form of pseudo-monetary expenditure. The concept of magic at large is inherently a celebration of and warning about the power of oratory, the capacity of a gifted speaker to change your sense of the world and yourself without necessarily appearing to do so. In today's hyper-stimulated and secular age, when nerves have been deadened by a 24/7 media barrage, it's hard to take such a notion seriously. But, much as we might pride ourselves on being too well-informed to fall victim to rhetoric, ours is still a society prone to flying off the handle at a slogan or a canny choice of words in a TV interview.

It's thus worth thinking about what "sorcery" entails, because to do so is basically to think about language's potential abuses and how to resist them. Games, however, have ceased to recognise this, assuming they ever did. In a majority of fantasy games, magic has become a tedious transaction, a matter of handing over so many "mana" or "magicka" points for such-and-such a tactical gain. It's part and parcel of the creeping claim that a game should be an economic structure at heart, characterised by predictable patterns of earning, a marketplace and "character development" (read: buying attributes that raise your earning potential) rather than, say, a good story or a thoughtful script.

Le Guin and Mieville's fantasies stand against that drift in different ways. In blurring sorcery with a discourse of technology and industry, Bas-Lag does allow for the notion of magery as a transaction - a science and a business, involving measurable inputs and outputs - but it also represents those transactions as horribly imperfect and risky. Cast a spell in Bas-Lag, and odds are you're going to damage yourself in ways you can't conceive. Earthsea, meanwhile, envisages magic as the act of taking part in the on-going articulation of what it is to exist - a question not of expending power in any mean quantifiable sense, but speaking the world anew. Here's hoping the makers of such rich fantasies as Dragon Age, The Witcher and Skyrim take a few of these ideas to heart.