PS2: The Insiders' Story

To mark the end of PS2 production, we're re-publishing our insiders' account of the console's success, featuring Chris Deering, Phil Harrison and more.

During these meetings, Deering and Reeves would offer incentives in exchange for exclusivity. These included a reduction in the platform fee, marketing support and new-generation dev kits.

"The last meeting of the day was with [Take-Two boss] Kelly Sumner," says Deering. (Reeves doesn't recall this being set up as an official meeting, by the way, but just "a few beers in the evening".)

"We picked up something called State of Emergency, which I don't think would have been on Xbox anyway. Then I said, 'What else have you got?'

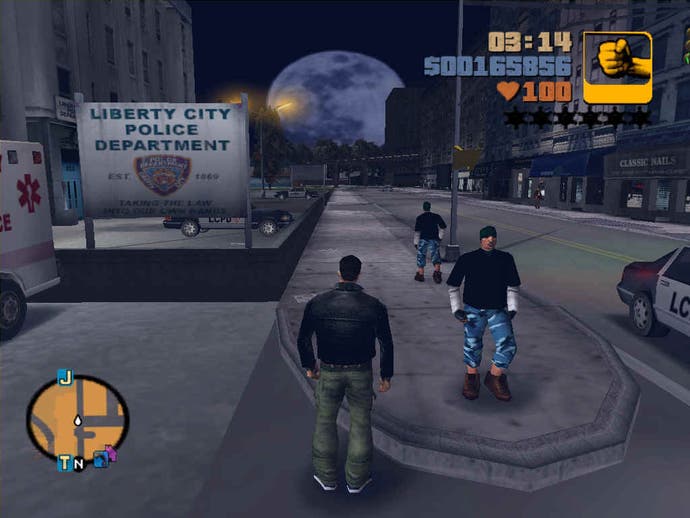

"And they said, 'Well, we've got this Grand Theft Auto game... I suppose we could do a deal on that.'"

"Our technical people had said GTA III was not bad. It was innovative, but not a monster. I had just heard it was good. So I said, 'OK.'"

The precise details of the deal have never been revealed but according to Reeves, "It was remarkably cheap."

These days, says Harrison, it's no longer economically viable to secure exclusives, due to the high cost of development. "So I think PS2 was probably the last era in which you will see that happen in a meaningful way," he predicts.

For all that publisher deals were important to PS2's success, Sony's in-house titles were also key. The list is long, distinguished and peppered with landmark games, from Gran Turismo 3 ("Probably the first game that lived up to the expectations of the console" - Duncan) to SOCOM ("The fact we were doing online gaming was amazing," says Brooke).

But the game most mentioned by Sony alumni when you start talking classic PS2 titles is ICO - even though it "never, ever had any commercial success", as Maguire admits. "It was ahead of its time. People weren't looking for a relationship between two characters who interacted on the screen simultaneously."

ICO was the poster child for a component of PS2 which was close to Kutaragi's heart - the Emotion Engine. That was the brand name given to the machine's CPU, which had been designed with a specific philosophy of game design in mind.

"Kutaragi was a visionary," says SCE UK PR boss David Wilson. "Taken on its own it might seem pretentious, but to call it the Emotion Engine was making a bold statement about what we were out to achieve."

According to Harrison there was science behind the concept, too. "The idea Kutaragi and his team of engineers established was that the CPU would be capable not just of number-crunching, but of delivering the kind of mathematical capability required to simulate emotion.

"That was a very wide and lofty goal and I don't think we realised it in quite the way we planned. But it was the start of a process where you changed the way games were developed, inside the code, to be more believable."

Harrison recalls attending a silicon chip conference in San Francisco where Sony's engineers presented the Emotion Engine in the form of an academic paper. "I was fascinated by the reaction because the hardcore silicon chip experts fell into two camps," he says.

"One was, 'I don't believe it. It's all made up.' The other camp was, 'I do believe it, but there's no way we're ever going to be able to manufacture it because it's too complicated.'

"Ken proved everybody wrong. You could build it, and you could build it in volume. That was the moment Sony Computer Entertainment went from being just a games company to becoming a major global player in silicon chip design."

However, it wasn't the Emotion Engine which gave PS2 the power to reach an audience beyond gamers.

"The DVD player was a massive part of that," says digital content manager Jim Smith. "I bought my first DVD player six months before the console launched and it cost £499. They still cost that when PS2 launched, at £299. So PS2 was the cheapest decent DVD player you could buy."

The inclusion of a DVD player helped to move games consoles out of the bedroom and into the living room. "You didn't have to tuck it away in case someone came round," says Fargher. "It almost became a lifestyle accessory - people were proud they had a PlayStation in their lounge."

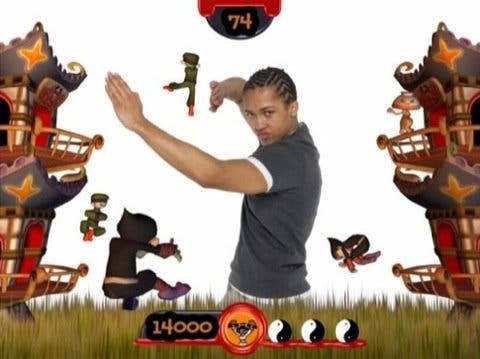

PS2's mass-market appeal was also increased by the addition of features which turned out to be more significant than Sony had imagined. "I think one of the defining features of the console, although we didn't really know it at the time, was the inclusion of USB ports," says Harrison.

"That proved to be a pivotal hardware choice. It allowed all kinds of alternative controllers to happen, from microphones to guitars to EyeToy."

It's easy to forget, in these days of voice-responsive cameras and magic light-up ping pong balls, that motion controlled gaming dates all the way back to PS2 days. And guess who was responsible for kicking the trend off?

"One of Phil's really great contributions was being passionate about EyeToy," says Deering. "It didn't have the full backing of the management over in the States. They thought it was too wussy, they were still SEGA-minded and anything that wasn't hardcore was possibly too effeminate for their image."

Harrison was EyeToy's champion right from the start. "It started when I gave a speech at the Game Developers Conference in March 1999. A guy came up to me afterwards and gave me his business card. He said something along the lines of, 'I think PS2 hardware is capable of doing machine vision, and I'd love to talk to you about it.'

"He ended up getting an interview and working for our R&D team in the US. And that guy was Dr Richard Marks."

Today, Marks is known as the man who explains the sciencey bits behind PlayStation Move and 3D gaming. But back then he was the creator of EyeToy, and the person tasked by Harrison with showing the technology to a room full of SCEE's software developers at an internal summit.

"I laid out a challenge," explains Harrison. "I said, 'Who wants to turn this into a commercial product? Because I think this is great technology, and it could be really pivotal for what we want to do in the future.'"

A young developer named Ron Festejo put his hand up. Harrison says he then did two very brave things: "Firstly, he voluntarily cancelled the project was working on. He said he'd seen other games that day which were better than his own game, and he didn't feel he could be competitive.

"Then, he said he really wanted to work on EyeToy. So it was a question of, 'Ron, meet Richard, now off you go.'"