Pok¨Śmon's collaboration with Daniel Arsham is a reminder of games' most existential threat

Art Attack.

Preservation is not a problem unique to video games. We've lost Homer's Margites, Shakespeare's Cardenio, and the end to Austen's Sanditon. We've lost Hitchcock's The Mountain Eagle, and London After Midnight, and a film nominated for five Oscars - including Best Picture - in The Patriot, directed by Ernst Lubitsch. And we've lost music, like the deeply influential work of Lead Belly.

But where games are unique, in their ability to slip so desperately through our fingers, is that they can be lost while still being so incomparably young. Game Boy cartridges last about fifteen years before their batteries give up. Unreleased versions of games are locked away in vaults. Even right now, games we "buy" evade true ownership. Our massive digital libraries are stored on Steam or PlayStations and Switches and Xboxes for only as long as we're granted a license to them.

The idea that your Steam games might just up and disappear is, obviously, a little alarmist. It's hard to imagine Valve or anyone else pulling that kind of stunt without an almighty stink. But the point remains the same: there is something distinctly transient, distinctly ephemeral, about the way in which we buy and play and collect our games. How they can become obsolete or locked down to specific platforms and how those platforms - Game Boys and PSOnes and unsupported old versions of Apple's iOS - become a little capsule of time in their own right.

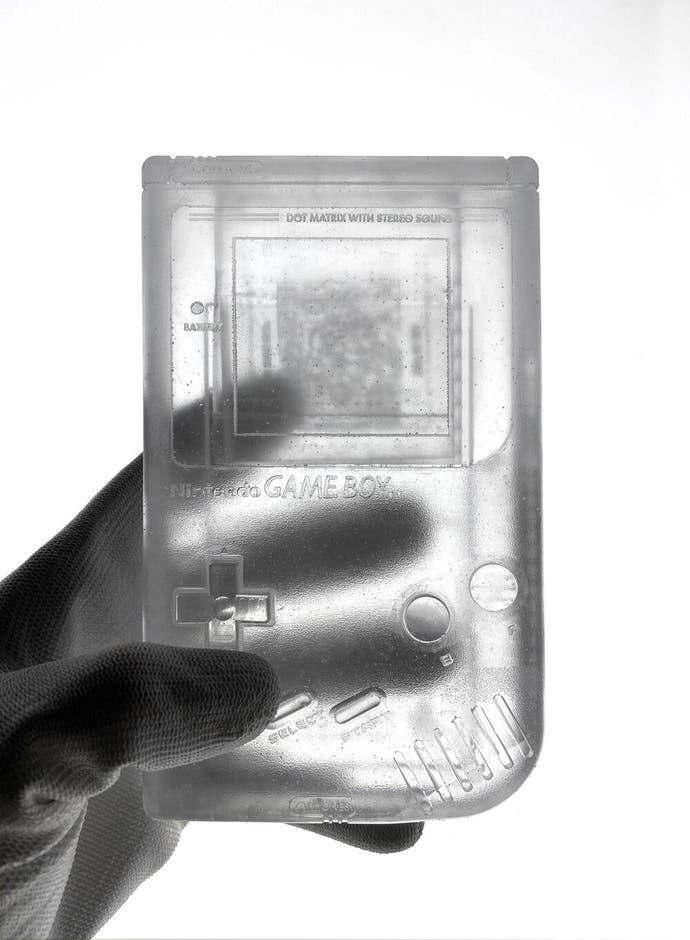

It's this, I think, that makes a rather strange collaboration between Pokémon and a New York-based artist called Daniel Arsham so surprisingly profound. Arsham's art is all about the idea of a sort of "fictional archeology". Hypothetical sculptures of things we find around us now, as they might be discovered in a thousand years' time - only with the artsy twist of making these sculptures from "paradoxical" substances. Bronze and crystal and the like, which look to be "growing" more than decaying, instead of the actual, literal materials from which they're made. He's already made a crystal copy of an original Game Boy, for instance, titled Crystal Relic 002, complete with a nice little Super Mario Land cartridge that slots in the back.

With Pokémon, Arsham hopes to "shift people's understanding about time in general". The goal is to get people to "step outside of their own timeframe" and use that as a way to look at our current, everyday life from a new perspective. Pokémon, being the behemoth that it is, was something he chose to use to do that. Whether that works or not is obviously not for me to say. That's the joy and - depending on your disposition - the nonsense of this type of art. But whether a blown-up bronze sculpture of a Bulbasaur with some crystals sticking out of it does anything for you is kind of besides the point. Which is to say: the point is games are a wonderful way to think about time. They're both entirely out of it, in their own immortal worlds, and a window into it, as little frozen snapshots of an era. And they're under a deeply existential threat, too - by their nature as purely digital things - because of their relationship with it.