Pok¨Śmon Shuffle review

Mostly heartless.

Eurogamer has dropped review scores and replaced them with a new recommendation system. Read the editor's blog to find out more.

One of the weird aspects of money is that it can make things feel cheap. And I mean cheap in a very specific way.

Take Pokéballs. Everyone knows the deal with Pokéballs. Sometimes they work and you get to capture a wild Pokémon. Sometimes they don't work and the wild Pokémon gets to flee. In a traditional Pokémon game, I am A-okay with this transaction. I may rant when a dice roll unexpectedly doesn't go my way, but I rant safely within the fiction of the game: I am a trainer, and that particular Pokémon has gone forever. Hope it wasn't a Psyduck.

In Pokémon Shuffle, though, this delicate fiction is compromised. I may have effectively paid real money to have that Pokémon battle, and I may also have paid real money for a special Great Ball with a better than average chance of making the catch once the standard Pokéball has already failed. When I'm paying for individual Pokéballs out of the same pot of money I use to buy a sandwich, or settle the electric bill, I take it a lot more personally when one doesn't work. More importantly, when I rant about a Pokéball failure in Pokémon Shuffle, I'm not ranting as a trainer. I'm ranting as a punter. Or, you could say, as a gambler.

And I appreciate that all of this is a bit weird. Pokémon Shuffle is a bit weird, really. It's a free-to-play Pokémon-themed match-three puzzler in which you move Pokémon faces around to battle their wild brethren, and, in purely mechanical terms, it's dull but largely semi-competent. It takes the Puzzle & Dragons approach to match-three, which means that you can move a piece from anywhere on the board to anywhere else on the board (for your first few minutes with such a forgiving design, you may suspect it's more spot-three than match-three). Then it dusts the whole thing with a thin layer of additional complexity, as you choose which of your Pokémon will populate the board in each battle - which Pokémon get to be the game's pieces, in other words - and then aim for a combo landslide and lots of four- or five-piece matches. Throughout its campaign it offers, if not actual fun, then a gentle kind of distraction, in the same way that it is a gentle kind of distraction to try and guess the four-letter passcode on my digital bus ticket each morning (today's was MOLD). It's not the sort of game you would generally find yourself getting worked up about. It's the sort of game you might forget you've played while you're playing it.

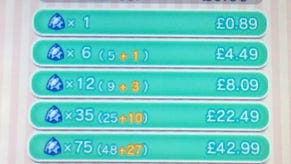

On top of this reassuring banality, the free-to-play business model actually seems relatively gentle - as long as you aren't in too much of a hurry. With no time pressure, and playing at a lazy rate, I got to about level 50 before I had to drop any money, and the next £8.09 was enough to get me into the low 80s. Dropping in and dropping out with long breaks, it would be hard to argue that I was being worked over by Wall Street here. The stages tend not to have nasty spikes, and those Pokéball captures actually seem to go in your favour as often as they don't, even if the meter at the bottom of the screen that measures "catchability" doesn't seem to provide too much real guidance to your overall chances of success. The problem, then, is philosophical. In Pokémon Shuffle you can pay to tip the balance in your favour: go into battle with an XP boost, or pick up an extra five moves for a fee when you've lost a match. In my own highly limited experience, this stuff makes me inherently mistrust the game, even as the wider game itself seems to suggest that it is actually playing things relatively straight.

A lot of this mistrust comes down to the way that the microtransactions are employed. You can buy a five-move boost at the start of the match, but if you have enough coins, the offer will also pop up at the end of a match when you are looking back on a few minutes all but wasted, and so your resolve is weakened. Ditto the Great Ball, whose pitch similarly appears at the point of defeat, just as a desired Pokémon is about to get away into the bushes. It makes the game seem cheaper and more grasping than it might otherwise appear. It's the John Riccitiello pay-for-a-reload idea, and it hinges on diminished price sensitivity. And then there's the energy system.

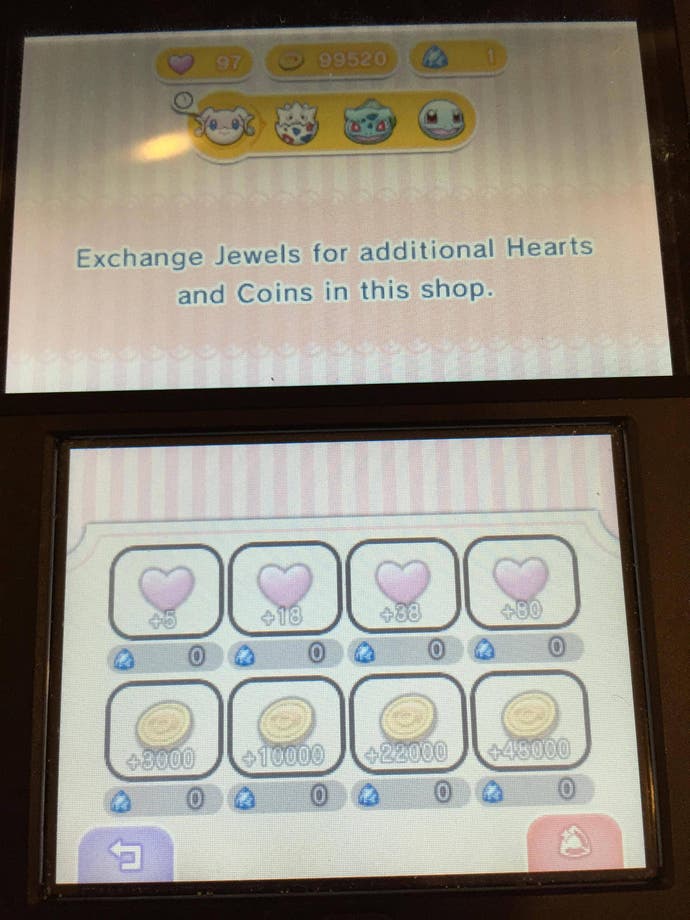

It is worth restating here that in 2015 we should probably be able to agree that free-to-play mechanics themselves work wonders in the right deployment and the right context. Hearthstone sells itself to you by the card pack, or by the trip to the arena where you might win something that you can keep, unless you encounter Wesley Yin-Poole early on. League of Legends lets you play as long as you want with the champions on rotation, and you only really have to buy the champions you'll actually want to hang onto. Pokémon Shuffle, though, uses energy: you can play as much as you want, as long as you have enough energy. That means hearts in Pokémon Shuffle. You start with five of them, you cash one in when you want to play a match, and they recharge over time. Don't want to wait? You can buy them.

There are two problems with this in Shuffle's case. The first is that the hearts take 30 minutes to recharge. 30 minutes isn't too bad, right? I agree, but I'm 36 years old, and 30 minutes no longer holds any existential fear for me. Half an hour? That's a sandwich, a quick scan of the emails, and a gentle, melancholic flip through the Advanced D&D Monster Manual I bought on eBay to remind myself that I'm old. For a five-year-old, however, the kind of person who is most likely to wrest any kind of brand-infused fun from Shuffle's crooked palace of moderate satisfaction, a half-hour stretches long into the distance until the horizon starts to shimmer.

I'm not worried about Shuffle forcing kids into spending sprees, because the eStore requires a credit card and, thankfully, young children's applications for credit cards are generally turned down. What I am a bit bothered by, though, is the fact that Pokémon Shuffle is an invitation for children to become frustrated - and these people find life frustrating enough already. I appreciate that think of the kids is a battlecry that's generally employed in fairly questionable situations, and generally by a right-wing tabloid, but this is a Pokémon-branded puzzle game on the 3DS, and I would say adding microtransactions to that is fairly questionable too. Equally, energy systems are often excused with a shrug and a cry of: Oh, just do something else for a while as it recharges. Hello, I reply. Have you met children? Adding to the grot somewhat is another fact: games with energy systems are effectively bottomless. They have rigged things so that, should you become a proper fan, they will never stop asking for your money.

So how does the money aspect break down? My colleague Tom Phillips has looked into it pretty exhaustively here, but the salient points are that you spend hearts to play matches and coins to buy optional in-game items, and you spend jewels to buy hearts and coins. Coins and jewels trickle in throughout the game from a variety of sources, but if you want a lot of jewels, you're going to have to wait a long time, or pay real-world money.

Again, not necessarily a lot of real-world money: the game is quite generous in this respect, and it gets more generous once economies of scale kick in. But in Pokémon Shuffle's limp case the very appearance of microtransactions really raises the question of the value of what you're paying for in the first place. There is an undeniable thrill to Shuffle's parade of familiar faces, but it strikes both ways. Take the Marshtomp, with that gaping leer rendered loveable by the sense of childish hope captured in the cartoon eyes. He's a beautiful piece of cartoon design, and it's not hard to look beyond him and see that the wider game has not been rendered with the same care and brilliance.

There is some cleverness here. You use your knowledge of Pokémon types to select the right load-out to populate the board with the most appropriate strengths before tackling a particular foe. Your foe can lay-down attacks that lock out parts of the board or introduce less effective monsters onto it. You can even charge one of your Pokémon up through matches to evolve and do extra damage, so long as you have the right doodad for them to hold. All of this, along with many of the inherent intricacies that belong with every match-three, is muted somewhat by the strong element of randomness that comes from having unseen pieces falling into a smallish playing area every time you make a match. You can make the right match given the visible pieces and benefit very little from it. You can match stupidly and be rewarded with an endless cascade of combos. Over time, if you play smartly you will definitely be tipping the balance in your favour, but 'over time' in a game where the energy recharge is set to 30 minutes involves the kinds of periods that might be better spent doing something else.

Elsewhere, alongside the main campaign with its parade of classic characters and regular trainer battles, there are Expert matches that give you a time-limit rather than the campaign's move-count to work your magic in, and there are Special stages where new enemies appear at regular intervals. You get a steadyish trickle of coins and jewels just for working through your foes, checking in at the online noticeboard, and even StreetPassing. Sometimes, something magical happens and Shuffle briefly flickers to life, too: matches that limit your moves to four or five rather than the regular 16 or so tend to be much more entertaining, as do matches that limit the number of Pokémon you can populate the board with, or matches where an enemy's power really forces you to employ proper tactics. In one battle mid-way through the campaign I watched as Espeon steadily froze chunks of the board until I was left with almost no room to play with. It was a brief delight to work out how to undo him.

Shuffle is a muddle, then: an acceptable distraction undermined by the grasping philosophy behind its business model as much as the actual amount of money it could cost you. Compared to the smartest of the modern free-to-play games, which are put together with a canny wit and sense of willing engagement, Shuffle's approach just feels primitive. This is the first Nintendo game you probably don't want your kids to play, in other words. Not because it will bankrupt you, but because, should they somehow fall for its sickly pleasures, they will eventually discover that all it really knows how to do is take.