Oxenfree 2: Lost Signals - one restless night of mysteries

See you in the obits!

If I remember this correctly, the movie American Graffiti starts with a close-up of a car radio frequency display. American Graffiti is about a group of young people wandering around on a special night. George Lucas' next film would be the one to take us out to a galaxy far, far away, but, even back in the day, on a crackly fourteen-inch TV screen, that radio shot in American Graffiti looked absolutely gigantic. It's just numbers and lines, and yet here was a panorama, lightyears wide, filled with deep mystery, somehow grown-up and somehow incomprehensible. Turn the dial. The needle scrolls, static twists into high notes and descends into a low fuzzy grumble before suddenly - implausibly - erupting into song.

Radio has always seemed the most shadowed and unlikely of technologies. Analogue radio: you dialed in, you tuned and tweaked and pretty much dowsed for what you were after. Where's Radio 1 gotten to today? And there was all this little stuff in between the big stuff, the actual stations, that as a kid I found even more interesting. I can still reel off the numbers of certain stations - long after my mum has forgotten the names of her children she will still understand what 94.5 means - but I can also recall long bored nights turning the dial through the darkness and enjoying the backwash tidal sounds of the gaps between. The gaps! Dead air. Almost empty space. Nebulas spinning. Moon dust. Black bubbles turning on the surface of fresh coffee. All images conjured because the gaps were mere sound. I wish we still had technology like this, technology that was spatial yet invisible, the very opposite of user-friendly. Something that whistled and sparked. Something murky, spooky, irascible, and filled with all that cursed analogue potential.

The Oxenfree games are all about radios, and they're also very good with the idea of gaps. The first Oxenfree dumped a bunch of kids on an abandoned island and saw them wandering and chatting and uncovering a supernatural mystery. It was a game about walking between points on the map and learning more about your companions through conversation choices. But it was also about that radio you carried, with a dial you could scroll through whenever you fancied, and which, in the right circumstances, could reveal a secret world and tear open holes in space and time.

But those gaps! It was in between the big events that Oxenfree really spoke, I think. It was in these gaps where you were headed somewhere or headed away from somewhere, where you suddenly realised something about one of the party members, or when you saw the balance of power shift in a relationship. Someone would reply to an off-hand comment with surprising honesty. Or someone would lie, and it would be obvious, and you would suddenly understand that you knew why they'd done that. Oxenfree's radio had lovely staticky oceans between its haunted stations. And it had these spaces within its narrative where you could actually take a moment to make sense of everything, or simply ponder how much you did not know.

Oxenfree 2 has another radio, and it has more of those wonderful gaps. AM waves breaking on dark shores, absolutely, but also a moment where your walking companion Jacob will ask to play a game of one-word stories to calm him down, or when he will start narrating his own actions to allow himself a sense of control over the uncontrollable. How small, how domestic and true. And the sense, as you learn about one another, is that at any moment you could pull out the radio and find a hidden synchronicity between your precise location and a precise spot on the dial. What might the game do then?

What Oxenfree 2 does most of the time is what Oxenfree 1 did. There's a new, slightly older cast - and it's largely just a double-act now, just Jacob and Riley, the player character - and there's the coastal town Camena, a new, larger location to explore. But Edwards Island from the first game is visible in the distance often, and the new cast are still uncertain and hesitant and navigating the barriers they've placed between themselves and the world in a way that feels very familiar.

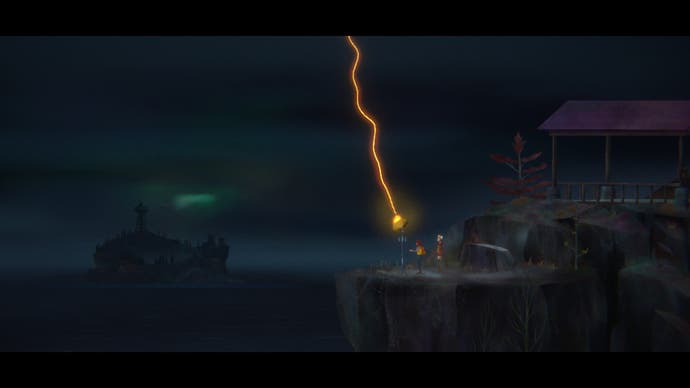

And the game's new narrative is eager to intermingle with the old. Oxenfree 2's story is more spooky dimensional shenanigans involving ghosts and local legends, and it's lovely stuff. Jacob and Riley, freshly minted colleagues earning a bit of extra cash, are out one special night planting radio antennas across Camena for some kind of research project. But there's a cult knocking around, and a bunch of weird kids, and a feeling that the boundaries between this world and another are a little thin in places. And then there's all that stuff that happened five years ago...?

(With its youthful chatting, its love of the night and a distinct thing for dimensional rifts, Oxenfree can feel a lot like Stranger Things - and it's perhaps no surprise that Night School, the Oxenfree developer, is now owned by Netflix. I don't think either Stranger Things or Oxenfree are copying each other, though. Rather they're both tuned into an older, weirder station, called the Montauk Project, a sort of grotty fictional conspiracy theory about government forces, time travel, and the Philadelphia Experiment. Montauk has an obsession with radio equipment and a story about a big vessel that goes missing, all elements that Oxenfree plays with to great effect. And googling around yesterday I learned that the pitch for Stranger Things was originally titled...Montauk.)

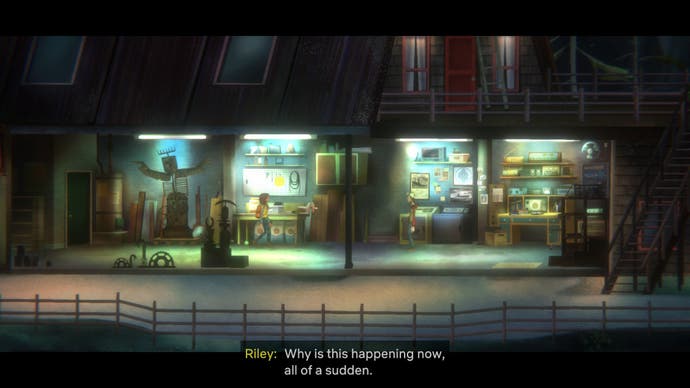

What do you do here? You wander from one antenna point to the next and have conversations and learn about each other. Jacob is a melancholic dork, I think: intelligent and isolated, and worried by the fact that he never left Camena. Is everything over? Will he never be enough? Riley, by contrast, is back in Camena after a stint elsewhere. She had a troubled childhood that may in some way explain the slight flinty quality in her voice in certain moments. Both main characters are initially awkward around each other, and Riley in particular can be deeply guarded. I came to think, rightly or wrongly, that she saw personal revelations as a form of capital at times. Both characters are through childhood and the ragged teenage wilderness to find that things are no clearer now than they were before. I wonder if a lot of Oxenfree fans will begrudge the shift in the age of the protagonists from Oxenfree 1 to 2, but I can see the value in it. Jacob and Riley are past that first set of crossroads only to discover that it's all crossroads out here - it's crossroads all the way down.

Camena is a beautiful place to explore, with the same powdery watercolours of the first game. There's a hint of the great children's illustrator Jon Klassen in Camena's love of spongey greys and browns and purples, and the same flair for invoking undergrowth with a few simple swipes and flecks of a pen, the same attention paid to different kinds of trees. As before, the camera is pulled way out, so you can see loads of the path ahead and the path behind, and so you're small and perhaps vulnerable in the middle of all this night. As before there's a small town and woodland and caves and trails. As before there are rocks to climb, and there's a new addition, I think, of ropes and grapple points, because Camena has a lot more verticality. As I walked, though, from one section of the world to the next, I thought about the radio I carried, and how the landscape is often most truly a way of pacing out your conversation, as you move across it like the timeline sweeping by in Adobe Premiere.

And you chat. I am kind of flattened by how good the conversation system is in Oxenfree. It's not just the web of personal story you are always piecing together with each dialogue choice. It's the way each choice is conjured in the brightly coloured speech balloons you select. You always get a hint of what you're going to say when you're picking a balloon, but the actual speech is always a surprise too. It's the way that the choices never boil down to good or bad, but live within that fidgety world - sometimes paranoid, sometimes casually cruel, sometimes oblivious - of real conversations with people we are thrown in with but do not know particularly well. Jacob remembers Riley from school. Does Riley remember Jacob? It depends. And it continues to depend even after we have selected an answer to this question and after Riley has interpreted it. It's those gaps again - the spaces within interaction that leave us wondering.

While the main cast is smaller, I found Jacob and Riley fascinating. Jacob is a babbler and a fidgeter. When we entered a new location it was always great to watch him wander off and peer at stuff, rearranging his legs, poking around in other people's boxes. Riley's character at first seems slightly sealed off - not least because we play as her. But as the plot gets weird and different paranormal elements intrude, we actually learn more about her life, and more about where she is at in this moment in time. Action is character, as Fitzgerald wrote. Never sure if I believed that, but it makes a strange kind of sense here.

As before there are simple puzzles, mostly placed, it feels, to cue you into the realisation that conversation is the real puzzle here. Some of these puzzles now involve dimensional tears, moments where you can travel between through different time periods in the same location. This stuff is actually pretty restrained in its use, but there's a thrill to it all the same. An early puzzle sees you using rifts to get around physical obstacles, but one that comes much later in the game has so much potential to it I want to play through again and really root around in there, testing its boundaries.

If the trees and rocks didn't already tell you this was fairytale country, there are also intrusions from other characters on the island, all accessed by a new walkie talkie gadget. This again is rather beautifully handled. A voice will crackle out of the darkness and often there'll be a task or a quest or a decision to be made, or some piece of information to tease out. But more than that, it's a radio person, an entity with a voice and dialogue but no face, no fixed location. The walkie talkie manipulates the unsettling magic you get when you only have someone's words and tone to make sense of them by. All these new questions! Who's staying up all night and why? Who's feeding you riddles and assures you that you already know their identity? What's the deal with Hank the paranormal investigator - I loved him - who signs off with a cheery, "See you in the obits!"

It's interesting. By the end of the adventure, Oxenfree 2 has tied up a lot of mysteries. It had for me, anyway, and with a web-like game such as this there's always reason to go back in, make different choices, and see what else is waiting in there to be solved. But there's this other feeling to everything too, just as there was in the first game. The radio, as before, is a gadget to be used when solving paranormal puzzles and whatnot, but it's always there all the time if you want it to be, placing different tissue-paper maps of sound over the island, different places and moods that change with each moment that passes, the same way a voice on the walkie talkie may have gone silent later if you didn't reply when they first hailed you. It makes Oxenfree feel less like a single mystery and more like a great, delicate palimpsest. There's space, and there's that space seen in different time periods. There's SCNTFC's restless soundtrack, strobing through endless moods, innocent in one instant and doomy the next. There's Jacob and Riley and everything that they are and could be and probably won't be. What would Jacob have become had he left? How would Riley have changed if she had stayed?

Somewhere within the shivering and twitching of all these layers, we get a night. A single night, walking across the landscape with someone new, stopping now and then to listen to the static or the shifting voices and songs of the dial. Wondering what could be, and what is.