Off Grid is about the principles of hacking

"I'll try not to sit on too many fences on this one."

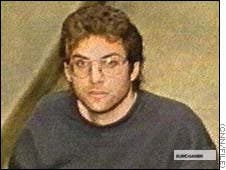

In the mid 1990's, after what lawmen rather fancifully described as a "countrywide hacking spree" across the United States, a man called Kevin Mitnick was arrested. He was charged with 25 counts of computer-related crimes which, legend has it, included hacking into NORAD, North America's aerospace defence system, inspiring the '80s flick War Games along the way. Legend or not, Mitnick served five years in prison that included eight months in solitary confinement and restricted access to the telephone.

Mitnick was a 'phone freak'. By recording the sounds played by a payphone when coins were dropped in, he could then play them back to the phone to call whoever he wanted, and also use the then-extortionate internet for free. The problem, Mitnick has since claimed, is that a judge got wind of this particular talent and came to believe that, if granted access to a phone in prison, he could whistle into the receiver to launch a nuclear missile. One version of the story is that the judge actually watched War Games, wherein young Matthew Broderick accidentally hacks into a NORAD-equivalent over the phone, and was so influenced by its portrayal that he was overcome with paranoia, handing out Mitnick's overly harsh sentence as a result.

What people do agree on - at least they do now - is the fact that despite its wide reportage in the press, Kevin Mitnick never hacked into NORAD, and he had nothing to do with the inspiration for War Games. In a weird, ironic combination of rumour and sensationalism, it would appear that Mitnick spent eight months alone in prison, with no access to a phone, because a judge heard about the exploits of fictional hackers in a film he had also fictionally inspired.

Mitnick's story is folklore to the modern hacking community. It's the ideal parable, outlining the ways in which public perception, filled with a growing paranoia that was manipulated by government, exacerbated by an ill-informed press and excited by the entertainment industry, could have a real and damaging impact on human beings. More specifically, on human beings who are also hackers. It also came up at EGX last year, of all places, when I talked to Rich Metson, who's one of a small team behind a little game called Off Grid.

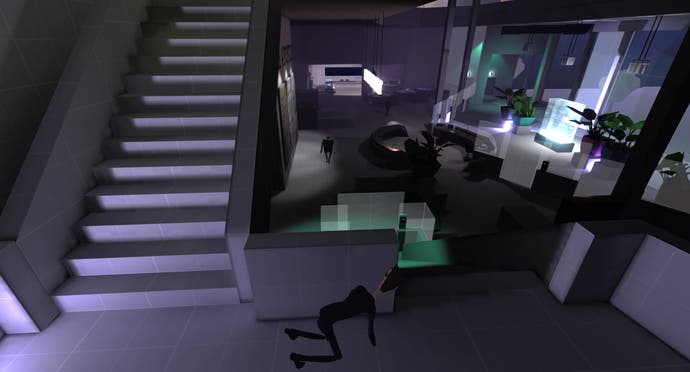

Off Grid is a game about hacking. We featured it in our showfloor roundup, after it piqued our interest with a unique take on the issue (despite being a hacking game, you don't really do any actual physical hacking at all). You play as a luddite, a bumbling dad out to rescue his teenage daughter, the real talent, from the faceless spooks. The scenarios you work through, like breaking your way into a newspaper's office to steal some crucial documents, or setting up internet-in-a-suitcase mesh nodes, mirror the exploits of hacktivists and their allies in the real world, with the help of your daughter's in-hiding associates. Instead of weapons you have a pair of smart glasses and a few other gizmos, and instead of karate chopping guards in the neck to knock them unconscious, you either find a way to avoid their line of sight or you're out.

What you pick up along the way are the principles of it all: the best hackers, or rather the best hacktivists, are detectives, following trails of data made available by what Metson might call a weak "digital posture", and leveraging it for access to the information they really want: hacking unencrypted messages between guards to find their interests and tune a nearby radio to them, granting you a window of distraction; finding files, yet to be deleted, from an internet-enabled printer's history to track down passwords. A hacker's currency, you learn, is data, and accessing data is often more about real-world sleuthing than smashing away at a keyboard with some green text flashing by on-screen.

But while that central premise is indeed smart, and its quasi-factual stages lend it a cutting, satirical edge, it's stuck in my mind for a different reason. Off Grid exists at a kind of weird, cultural intersection, where modern history, and contemporary events, and pop culture and the ridiculous, self-defeating conversations we keep having about politics in games all collide and mangle up together, and a lot of that is brought to it by Metson himself. It covers the principles of hacking in an entirely different sense of the word.

Metson describes himself as "involved in the hackspace." He started out in metalworking and art, got bored and taught himself how to code, got a degree, and moved into animation work for video and advertising. After a short while that started to grate too - "I wanted to make stuff that was more important than toothpaste adverts" - and so, whilst working his way through environmental and political protest groups like Occupy in East London, he one day found himself at an internet security conference in the States, where speakers professed their ability to provide "internet-in-a-box" devices for around $90 a pop. At the same time, the US was spending millions on dropping these devices into the Middle-East, to help the Arab Spring keep on springing.

Suddenly it all falls into place: "I thought I was going to make games about environmental stuff, and then was like, no activism exists without the internet, so actually I'm going to make a game about mesh networking, and this was 2010... things just got worse and worse and worse."

Seven or eight years later, Metson now has "friends and connections who are ex-Anons [members of the Anonymous hacker community], ex-members of LulzSec or members of LulzSec" and is close to people like Lauri Love, who is currently fighting extradition from the UK to the United States for computer-related crimes that could land him an up to 99-year sentence. Metson is fierce in his beliefs that these enormous US sentences, the UK's gradually eroding resistance to them, and the wider, underlying culture of fear and paranoia is directly caused by a mistaken public perception of hacking and the hacktivism community.

He's keen to bring up examples of how the world gets it wrong. "Some of the work they [Lulzsec members] did through the channels of Anonymous was really important, like they found out that there was a military industrial complex within the intelligence services and they found out that private contractors, within the intelligent services, were working directly with people like CitiBank to undermine people like Wikileaks. So you have private corporate firms, working with financial institutions, to undermine free speech within American systems."

We go through Wikileaks to Antifa, and the parallels that group shares with Anonymous and the problems of self-identifying under a vague mantle; he talks about the Computer Chaos Club finding a weakness in the German election system; Lauri Love pitching in to help patch up the NHS after the enormous hack it suffered last year; Phineas Fisher, the hacker who exposed the sale of weapons-grade spyware FinFisher to regimes in places like Bahrain and Sudan, as well as a range of other countries around the world, including Britain.

It goes on, but one example sticks out - and it keeps coming up: Kevin Mitnick and the problem of public perception.

Given the weight Metson placed on stores like Mitnick's, I wondered what he thought of games that have traded on their depiction of hackers in the present day. What did he think of, say Watch Dogs 2?

"I'll try not to sit on too many fences on this one. I was really unhappy with both of the Watch Dogs games ... Those folks at Ubisoft did attempt to get in contact to research it. I think on many levels they miss the point."

"My particular criticism - whether it was an interesting or well-executed pastiche or not - comes down to the fact that hackers in that game are portrayed as violent, and by nature they are non-violent - even when they're criminal, hackers are non-violent. They're about the most non-violent criminal you can find."

Metson was enthusiastic throughout our conversation, which often felt more like the kind of crony-bashing rants you'd get into with a university friend down the pub than an interview with a developer. But he prickled when it came to this point. "Hackers who fit into the hacktivist realm, fit into a kind of civil disobedience on the internet that is something that we need to protect."

"Civil disobedience is allowed within the physical world of politics for very good reasons, so why is it not allowed within the digital realm? Why is that broadly covered by the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act? Or the sorts of charges that get laid out here in the UK?"

His connection of Mitnick's case and something like Watch Dogs 2 is based on "the way that Watch Dogs 2 deals with activists - ethical, ethically-minded hackers - in the same breath as them being violent and garotting innocent bystanders with a pool ball on the end of a string, and with a rocket-launcher that they 3D-print and will use to gratuitously blow up grannies in stores, or whatever else as part of undermining whatever the Facebook pastiche is in the world there."

"It's massively negative and damaging to the fact that there is a genuine and real hacker culture that contributes to understanding [issues like] whether our voting machines are vulnerable."

Metson's politics - his beliefs - are inextricable from his game, and so all of a sudden Off Grid has value regardless of its satirical, almost jovial tone, it's mechanics, or even any of its content. Regardless of if it's actually any fun to play. It is made by a person, who exists in the world and is therefore inseparable from its context. It's a work of politics and a work of entertainment that's immediately interesting purely by virtue of the world in which it exists, and the fact that it exists within it. It's the perfect, Adornian thing: it's worthy of attention not in spite of its politics, or its commercial sale, or it's entertainment value, but because of all of them at once.