MLB: The Show can make you feel the frustration and isolation of the world's greatest athletes

If you build it...?

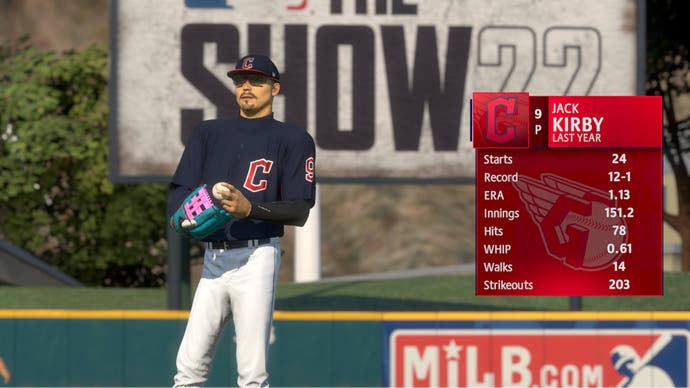

Despite being raised in Britain, last year I started playing MLB: The Show 22' as part of a growing fascination with baseball spurred by the game's cover star, Shohei Ohtani, a literal once-a-century talent. I created a character in imitation of him, Jack Kirby, a two-way player with the ability to both regularly hit home runs and pitch at an elite level. This was considered genuinely impossible outside of a video game before Ohtani. Since I was still learning the sport, the majority of my time was spent in the career mode, Road to the Show.

Personal achievement is the end goal of Road to the Show. Teams are set up to be deliberately transitory-you're drafted through a somewhat baffling conversation tree, and you move through two minor-league teams over the course of a few months. Because you only take control of your character for the moments they actually play, winning individual games, or the season, is almost entirely out of your hands. You can pitch perfectly, or score two home runs, only to discover your team lost by a huge margin. All that matters is that your individual stats go up, and your contract goes up. Theoretically, your money should go up too, and your career income is placed teasingly at the bottom of the stats page.

But here's the thing MLB: The Show reflects real-life MLB contracts, and that means it takes at least two years playing for a team to have any ability to renegotiate salary above the league minimum, and up to six years to gain the ability to go into free agency and change teams, regardless of the wealth the player generates for a team. This means even though money is one of the only meaningful long-term goals to strive towards, playing every start means it can take hundreds of real-world hours to negotiate a raise or change teams.

By the end of my second in-game year, Jack Kirby was the greatest player alive on the field, but what's fascinating is that MLB: The Show forces you to reconcile with the fact you can be that great and still be paid the minimum wage for a ball player. I spent an enormous amount of time staring at a locker room, looking at Jack his phone, bored out of his mind. I won the world series, only to come right back to see Jack doing exactly the same thing he always did: staring at his phone, stagnant. Even though the game would never outright say this, you feel like you've been exploited, a refreshingly weird feeling to get from a yearly sports game.

There's a particularly taunting moment where you call your agent, say you want out of your contract, he says he's "working on it", and then he doesn't call you back for half a year. To get a major raise or switch teams, my options were to either keep playing all my games for six years, which would take hundreds of hours, or to simulate the game until free agency; but six years is such a long time in baseball that any team I signed with, and Jack Kirby himself, would likely be left completely unrecognizable once those years of simulation passed by.

The funny thing is, this malaise is an excellent replication of baseball. Shohei Ohtani himself is approaching his sixth year with the LA Angels and was paid the league minimum salary for much of that time despite being arguably the sports player ever. The average retirement age of an MLB player is under 30, meaning a huge portion of players crash out of the system before getting a chance at the 'real money' offered by free agency. This, in itself, is the result of over half a century of union and players association victory, but it's still far from ideal. Official sports games often render their sports with a plastic, family-friendly sheen, but look close enough and you can still see the scars and ghosts left by the real people who inspired them.