Me and WWE

When Tom met Paul.

Kayfabe is the pretence. It's being in character. It's wrestlers who are baddies (heels) and goodies (faces) not being seen together in public – especially by the younger kids (WWE's audience is skewing younger and younger as it haemorrhages viewers to the more violent UFC). Kayfabe is the taunting, the monologues, the skits and the backstage interviews.

More importantly, it's the fourth wall, and behind it lurks a secret world of incredible travel and performance schedules, extraordinary individuals and pantomimic businessmen like WWE proprietor Vince McMahon. Glimpsing the reality beyond the fiction is as much fun as The Work itself.

The money men are not averse to using themselves and their jobs as part of the storylines, either: WWE stock fell suddenly in June 2009 when McMahon announced that he had sold WWE RAW to Donald Trump and some news organisations reported it as fact. (McMahon "bought back" his show the following week.)

The most recent (and initially brilliant) example of kayfabe influenced by real life, however, was the reintroduction of Bret Hart (despite retirement, and despite the fact Hart has a hole in the base of his skull due to wrestling, which led to a stroke) and the settling of his feud with Shawn Michaels and Vince McMahon, which began all the way back in 1997.

Back then, Hart was WWF Champion but wantaway. He decided to join Ted Turner's rival WCW (ironically, WCW was eventually bought out by WWF anyway) and needed to lose his championship before he left.

But despite the considerable personal and professional tension between Hart and WWF's new poster-boy, Michaels, he and McMahon agreed he would not lose it at his final pay-per-view, Survivor Series, taking place in his homeland of Canada. He would defend it in a brilliant match with Michaels that ended in a disqualification, and vacate it subsequently.

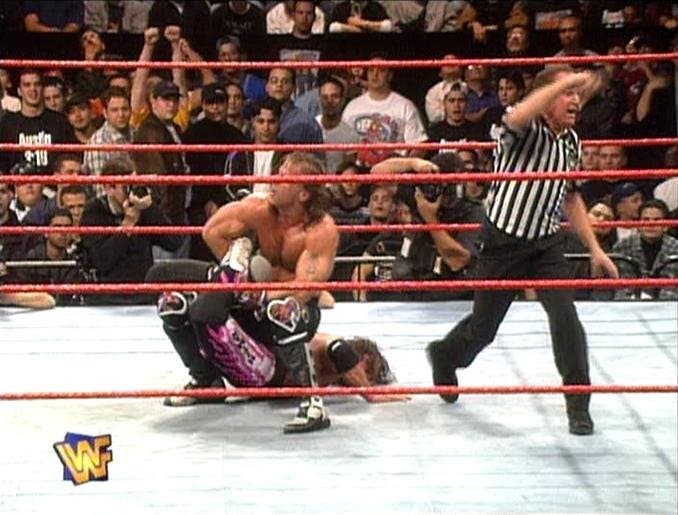

What's more, the match would have a spectacular climax. Michaels, whose edgy ring persona was a controversial new dawn for the then-Federation, would get Hart to the mat and apply the Canadian wrestler's own signature finishing move – a submission hold known as the Sharpshooter.

The Sharpshooter is a variation on the Boston Crab: the aggressor weaves his prone opponent's legs around one of his own, locking them into place by looping the uppermost boot through the right arm and holding tight, then twists his opponent over and squats down in a sitting position on his back. The idea is that it applies unbearable pressure to the lower back, although it's actually quite comfortable.

Hart would reverse the Sharpshooter so that he was applying the same move. The match would then degenerate into a brawl following outside interference, leading to the DQ. Under WWF rules, a championship cannot be lost by disqualification.

Instead, as Michaels applied the lock, a ringside McMahon grunted, "Ring the bell." The referee signalled the announcer, who called the match as a Michaels victory – even as Hart reversed the move as planned. He had never submitted because that wasn't in the script.

And so, for a few glorious minutes, the defrocked Hart, McMahon and his fellow conspirators (including Michaels, whose collusion was later exposed) were operating with scant regard to kayfabe.

We were seeing real emotions: McMahon's hatred for his traitorous world champion, realised; Michaels' guilty plunge to ringside and sprint to the locker room, not knowing what Hart would do; and Hart himself, who stared at the shellshocked crowd in disbelief, then leant over the ropes and spat in McMahon's face. The episode was christened The Montreal Screwjob.