Mafia 3 review

Bug easy.

Video game bugs may annoy and amuse, but they can also be strangely revealing. I've encountered plenty of minor and major errors in Hangar 13's Mafia 3, a hard-to-love but undeniably ambitious open-world crime sim, set in a thinly disguised remix of 1968 New Orleans. A few hours into the story, I was driving out of the bayou when the game's shadows went haywire, spinning around objects as though the sun were a police searchlight. Later, I somehow managed to impale an unconscious bartender on a stool, terrifying an old woman so much that her coffee cup became magically affixed to her hand as she ran for the exit.

And then there was that time I peered into a prostitute's dressing mirror during a raid on a rival gang's brothel and saw a corpulent, buck-naked white man, trapped like a frozen chicken in a purgatory of PS2-grade pixels. I'm not sure what the game's African-American lead Lincoln Clay made of this - the result, it seems, of a glitch whereby reflections lag a few seconds behind the action - but in that plump, affable spectre I belatedly recognised myself: another in a long line of privileged, complacent white guys, lurking in the background with his hands on the levers and buttons of the world.

This may sound melodramatic, an attempt to force my own political conscience on the game - but Mafia 3's greatest achievement, I think, is that it creates and sustains a space for such musings. Racism, intolerance and disaffection of all kinds are everywhere in Hangar 13's New Bordeaux, threaded into the emergent dialogue and art to an unprecedented degree. Opt for a stroll along the riverfront after clobbering a snitch, and you may stumble across a group of black dockworkers debating the merits of non-violent protest. Enter a jazz bar in the French Ward, with its faded wooden shutters and background simmer of stripclub music, and you might overhear an evangelical diatribe about interracial marriage.

Car radio stations run the gamut of innuendo and opinion, from starchy country and western DJs who witter on about the evils of pot and free love, to legalisation activists who hold forth on the covert bigotry of the war on drugs. White NPCs may not take kindly to Lincoln's presence in certain areas, it goes without saying. Police officers will pivot to eyeball you as you pass, muttering under their breath. Certain shopkeepers will call the authorities if you linger too long in the aisles.

This isn't just a virtual city with a point to make about prejudice. It's a virtual city that is founded on prejudice - a setting that, for all its numbskull pedestrian behaviours and low-resolution assets, often genuinely looks and sounds like the product of decades of ethnic struggle and systematised abuse. The portrayal of social division isn't binary and overt, but intricate, entrenched and unresolved, bursting forth at every level of the representation. The script's ethnic slurs aren't deposited with a guilty flourish, as in many a "socially conscious" blockbuster, but are simply part of how characters of the era speak, a complex set of overlapping registers. There's even room for a little social comedy - the radio ad for the Royal Hotel in Downtown New Bordeaux, for example, voiced in plummy English with the British national anthem heaped on top for good measure.

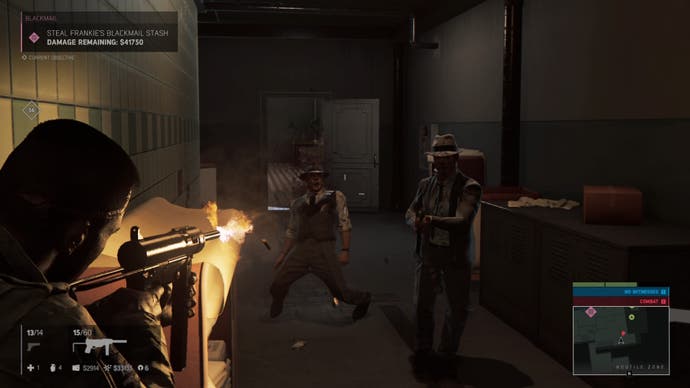

If prejudice is everywhere in the world of Mafia 3, however, it's also seldom that impactful, beyond the engagingly acted cutscenes and wealth of incidental writing. The key problem is that the game has inherited its open-world design and mission structure from Assassin's Creed and Grand Theft Auto: a soup of by-the-numbers fetchquests, outpost infiltration sequences and firefights that depends, above all, on the player enjoying more or less total freedom of movement and freedom from consequence.

This is a power fantasy at heart, a framework built to entertain rather than tap-dance across cultural fault lines or dig into the experience of discrimination. So while the cops may call you "boy" or "kid", they won't take umbrage when you careen along a street in your muscle car, side-swiping convertibles and knocking over traffic lights - anything short of pulling a gun or running somebody down is perfectly above board. At one point I stood on the hood of a station wagon in full view of several officers, throwing punches at the air to no reaction. You could argue that to cast an African-American in an empowered role that has been historically handed to white characters is constructive, but I think the effect is to bury New Bordeaux's artfully handled tensions and schisms, reducing a thoughtful representation to clusters of dots on the minimap.

It doesn't exactly add to the impression of a world that's out to get you that the game's AI is so miserably dumb, reliant on flanking strategies and alertness states that went out of fashion roundabout the launch of Metal Gear Solid 2. You can whistle to attract sentries, throw distracting objects and exploit a tacit last-known-position system to get behind people, but an Arkham or Hitman game this most certainly is not (though certain upgrades - the ability to summon hitmen, or cut off phone lines to thwart a call for reinforcements - do create space for more involved infiltration strategies over time).

To the writing team's credit, the entertaining plot has a go at justifying the generic mission design with reference to Lincoln's military career. Told in part through a frame narrative of stock newsreel footage and interviews with key characters decades later, it sees you raising your very own crime syndicate from the ashes of another, following a murderous double-cross at the start of the game. Seeking revenge on the city's reigning dons, Lincoln adopts a scorched-earth tactic supposedly developed during guerrilla combat with the Vietcong, taking over rackets and killing made men in each district to flush out the local boss and thus trigger a story encounter.

In the process, you become surrogate parent to a trio of deposed mafia lords: the violently maudlin Burke, Mafia 2's well-preserved Vito Scaletta and Cassandra, leader of New Bordeaux's Haitian mob. The lieutenant system creates some worthwhile campaign dynamics - having conquered a district, you can assign it to an underling to unlock new weapons and perks at the risk of pissing off the other two. It also lends the narrative something of a progressive vibe, as what you're effectively doing is putting together a grudging anti-establishment alliance of Italian, Irish and Haitian Americans, a sort of United Nations of the underworld. That faint hint of a feelgood ending is quickly lost in the bloodshed, however, as one capo after another falls to Lincoln's trusty combat knife. And if the campaign has more verve than you might guess from a glance at the mission list, the element of repetition, the AI's flaws and, of course, the bugs take their toll over time.

Though dependably vicious and, depending on your decisions at points in the story, perhaps beyond redemption, Lincoln himself is a likeable creation - not quite as embittered and corroded by ethnic feuds and the system's failings as other characters in the game, but a long, long way from an emancipated superhero, years ahead of his time. That's thanks as much to the animation as the strong writing, which puts across a lot about Lincoln's personality, moment to moment - the way he drums his fingers on a car wheel during a stakeout, slaps his hand against the wall when you slide into cover, or bounces on the spot after aiming a gun.

The overall impression is of a man with enough personal baggage to fill a safehouse, trying to carve out a space for himself in a universe that despises him. Both he and his city deserved a better game than this one.