It's not easy being green: a brief history of orcs in video games

From A to Zug Zug.

When we first meet the young orc warchief Thrall in Warcraft 3, he's just woken from a nightmare; visions of orc and human armies clashing on a battlefield as the sky burns above them.

"Like fools, we clung to the old hatreds," a voiceover laments. It's rendered stunningly, this battle, in an early progenitor of Blizzard's now-renowned cinematics. But unlike in the previous two games, there's no glory to it. The morally simplistic battles of old are chronicled in the language of regret. Old triumph is revised as cyclical folly.

Thrall wakes from his vision and jolts up in bed. We can see terror on his face at first, and then... sorrow. And just like that, Warcraft's orcs are given something they'd never really had previously:

A chance to be people.

As far as I knew at 10 years old, no-one had 'invented' orcs. They just were. Like giants, fairies, or dragons. I'd fought them in HeroQuest, all protruding lower canines and piercing red eyes, brandishing meat cleavers and falchions above their heads. I'd defended castles from them in the Dungeons & Dragons board game DragonStrike. I'd even controlled orcish warriors and catapults and giant snapping turtles in Warcraft 2: Tides of Darkness. I didn't have the language for it at the time, but I'd placed orcs in the realm of folklore, a part of our collective storytelling public domain. That is, until my Year Five teacher jokingly called a story I'd written a 'Tolkien rip-off' and lent me her personal, faded hardcover of The Hobbit. It was, I thought at the time, even cooler than C.S Lewis. It had bigger battles. Dragons. Gollum. And a lot more orcs.

Orcs.

Evil. Disposable. Generally up for a party but will probably end up killing each other. Disposable. Bad at tactics but too numerous for it to really matter. Disposable. Just good enough at fighting to make our heroes look cool, but never good enough to pose a real threat.

Disposable.

This isn't what makes them endearing, and enduring, though. Sure, they're often hilarious. Mostly fearless. But they're also perpetual outsiders. Sometimes, like Warhammer 40,000's Goff Rockers and Blizzard's mohawked trolls, they're punks. Fantasy's counterculture. Scrappy. Resourceful. All DIY aesthetics and painted banners. Backs against the wall, grog held high in the air with one hand, and a long, gnarled, green middle finger on the other.

The first level of Warcraft 3's prologue starts with a line of text on a loading screen. A single line that grants Thrall, and by extension the Horde, more agency than the previous two games combined.

"Somewhere in the Arathi Highlands, Thrall, the young warchief of the orcish Horde, wakes from his troubling dream."

His troubling dream. Imagine that. Thrall is troubled. Not angry. Not vengeful. Not somewhere on the spectrum between recently having finished killing humans and planning out which humans to kill next. But troubled. When he speaks to the prophet Medivh in the following cutscene, his voice is measured. A tone of resolute contemplation, in sharp contrast to the ornery Fozzy Bear gargles that delivered the old game's orcish text scrolls.

Playing the Warcraft strategy trilogy in order today, this change seems sudden. Jarring, even though it had been in the works for a while. The character Thrall was conceived for the adventure game Warcraft: Lord of the Clans. The ill-fated, darkly comedic project imagined the warchief as a sardonic, wise-cracking Guybrush Threepwood type. Very different from what we'd eventually see in Warcraft 3, sure, but also much different from any orc in the series before. The first human we meet in the game - Thrall's jailer - is cruel and clumsy, a stark contrast to noble imperialism present in previous depictions of the Alliance. By the time of Lord of The Clans, the orcs have been corralled to reservations, made slaves after their defeat by humans. For the first time in a mainstream fantasy game series, orcs are portrayed as victims, not aggressors. Even the name, Thrall, evokes servitude and chains.

Despite its eventual cancellation 18 months into development, the story of Lord of the Clans would later be retold and canonised in a novel with a much more contemplative tone, released a year before Warcraft 3's release. In that same year, 2001, another Warcraft novel named Of Blood and Honour reimagined the orcs in similar ways. But we wouldn't see these new orcs in action until Thrall first stepped out of that tent.

Early depictions of noble orcs are about as common as beardless dwarves. The odds were stacked against them from the start, really. The world 'orc' is believed, by some, to have been derived by Tolkien from the English epic Beowulf. It appears in the poem as 'orcneas' - an evil tribe, condemned by god. Another possible corollary - and one Tolkien would likely have been familiar with - was the Saxon term for the Norman invaders. Here, 'orc' means 'demons' or 'foreigners'. The link becomes even more apparent when you consider - as the historical novelist Kate Sedley asserts in Tintern Treasure - that the Anglo-Saxons called our world, as a place between heaven and hell, Middle Earth. A Middle Earth they tried to defend against 'orcs' at the Battle of Hastings.

How much of this history was actually relevant to Tolkien is unclear, though. In a letter to Scottish novelist and Lord of the Rings proofreader Naomi Mitchison, the author writes: "the word is as far as I am concerned actually derived from Old English orc 'demon', but only because of its phonetic suitability."

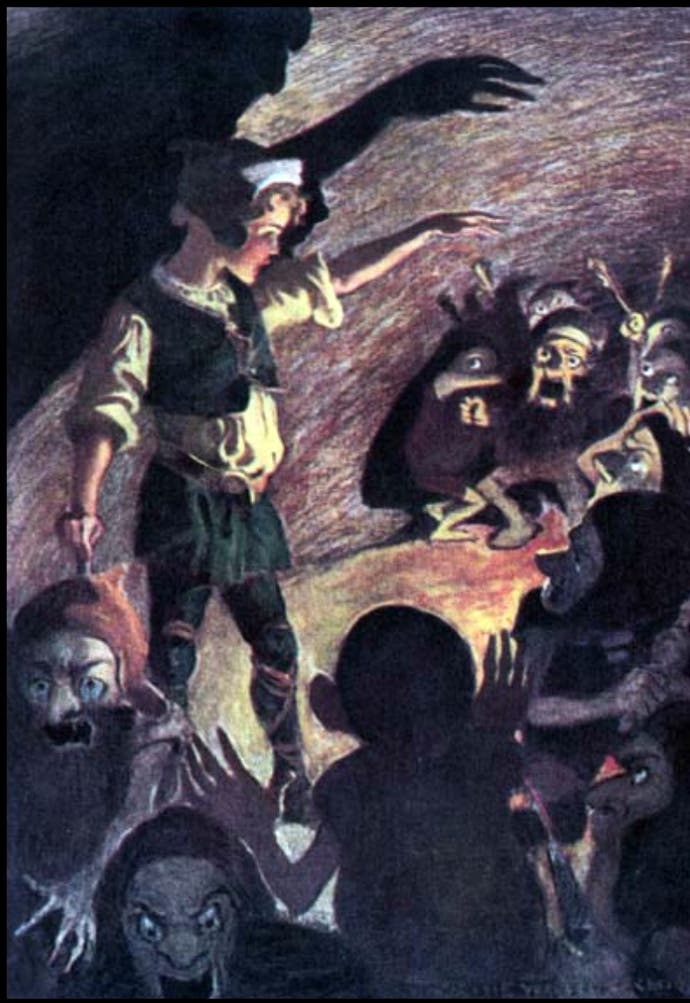

Pour one out for the green-skinned lads, othered from conception by an etymological whim. They didn't fare much better in terms of appearance. George MacDonald's 1872 fairytale The Princess and the Goblin - a childhood favourite of Tolkien's - is widely credited with inspiring the author in the creation of his own goblins and orcs. MacDonald's story describes them as a "subterranean" race, "called by some gnomes, by some kobolds, by some goblins."

"Not ordinarily ugly, but either absolutely hideous, or ludicrously grotesque both in face and form."

Which doesn't differ all that much from Tolkien's own, uh - let's say antiquated for now, though back to this later - description of orcs.

"... they are (or were) squat, broad, flat-nosed, sallow-skinned, with wide mouths and slant eyes; in fact degraded and repulsive versions of the (to Europeans) least lovely Mongol-types."

It's also worth clarifying here that to Tolkien, 'orcs' and 'goblins' are the same thing. The divisions in size and hierarchy between goblins and orcs is something fantasy has iterated on since. Don't tell an orc that, though.

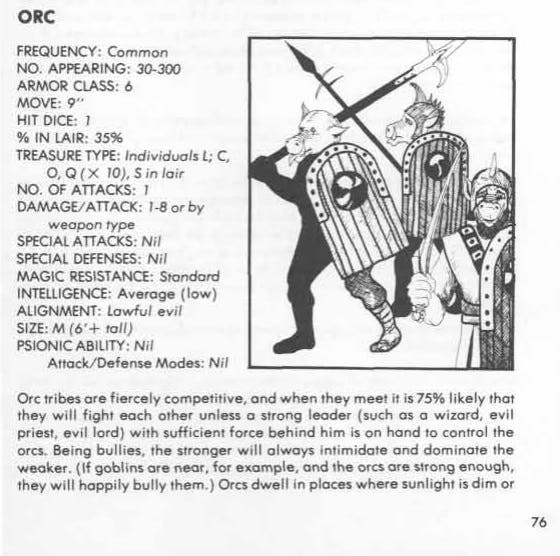

From here, the orc's first mainstream appearance in tabletop roleplaying was in the 1974 Dungeons & Dragons 'White Box Set'. Borrowing many Tolkienian tropes, orcs appear here as evil and warlike, harboring an intense dislike for sunlight. Relatable. They feature again in the original 1977 Monster Manual (the primary bestiary sourcebook for monsters in D&D), where several orc 'tribes' are listed. This dodgy correlation between low intelligence, aggressive creatures and tribal societies was rife in traditional fantasy, and one of the major tropes Warcraft 3 would later grapple with. For now though, orcs were firmly disposable minions of darkness.

Even in the 1977 Monster Manual, though, orcs are missing one of their most famous traits: they're still not green. Tolkien's were described as "swart" and "sallow". The Monster Manual describes them as "brown or brownish green with a bluish sheen". For popular codification of orcs' now-ubiquitous green colouring, we have to look to another tabletop game.

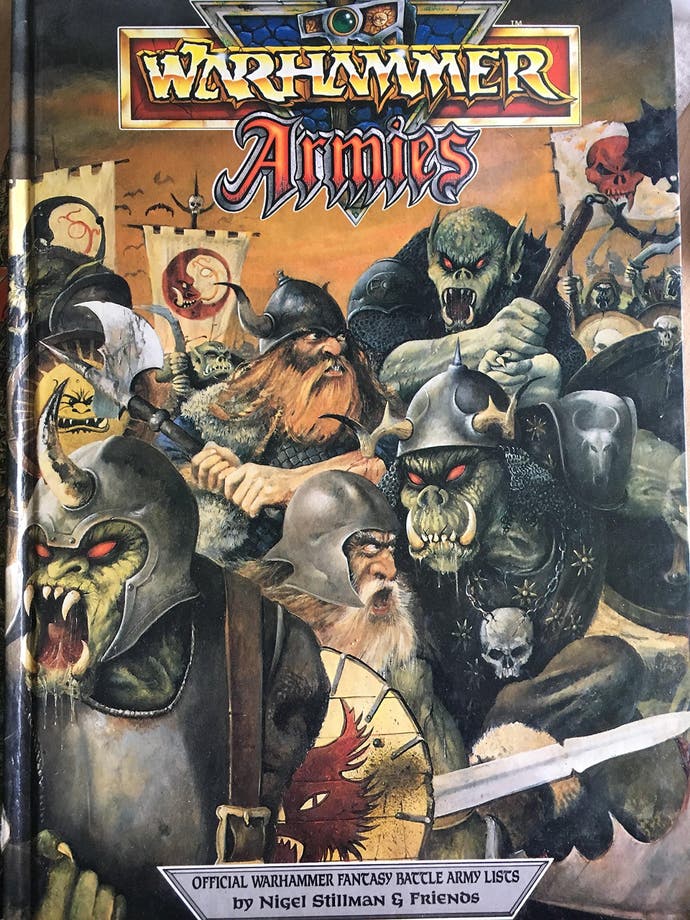

The (widely considered to be apocryphal) story goes like this. Someone at Games Workshop in the 80s is painting their orcish army, but runs out of the obviously correct purple paint halfway through. Frustrated, but feeling resourceful, they reach for the same grass-green a colleague has been using to base their dwarves, and lovingly slather each orcish muscle and jutting jaw with it. Everyone who sees the army the next day agrees: that's orcs, baby. And so, the greenskins are born.

True or not (and likely not), Warhammer does seem to be the turning point for green orcs to become the norm, although they wouldn't be called 'Greenskins' just yet. Warhammer's collected horde of orcs, goblins and other related lads are still referred to as 'Goblinoids' all the way through their first army book in 1988, up to the 4th edition Orcs and Goblins. Despite the absence of the term 'greenskins' however, Games Workshop's orcs are, primarily, uniformly green from 1988 onwards.

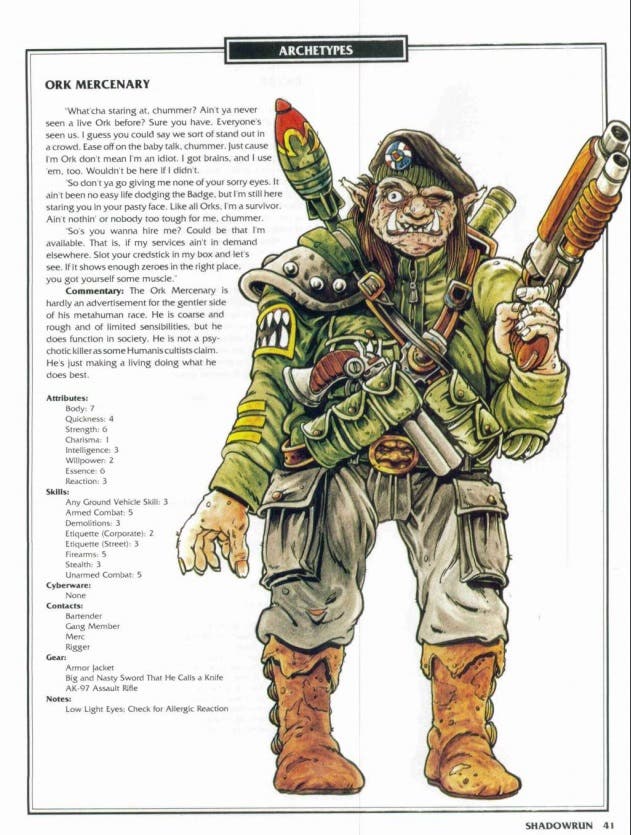

While Games Workshop's Space Orks, introduced in 1987's Rogue Trader ruleset, continued in the tradition of warlike, generally unsympathetic orcish depictions, the first edition of Shadowrun, published in 1989, was a little more nuanced. The 'Ork Mercenary' class features the following description:

"He is coarse and rough and of limited sensibilities, but he does function in society. He is not a psychotic killer as some Humanis cultists claim. He's just making a living doing what he does best."

Despite a few early attempts, such as Shadowrun's, to grant the orcs some humanity, they largely remained the same one-note villains. As the developers have confirmed, it's Tolkien and Games Workshop's orcs that Warcraft: Orcs and Humans drew the most inspiration from.

Thanks to the influence of D&D, however, Warcraft: Orcs and Humans was a long way off from being the first game to feature orcs - even setting aside games that use the D&D or Warhammer licence. 1980's Rogue (of roguelike fame), 1985's Bard's Tale, and 1987's Megami Tensei all feature a variation on either Tolkein's antagonists, or their D&D adaption. Megami Tensei is especially notable, as the orcs it features serve the demon Orcus: the historical Latin god of the underworld, and another speculated etymological origin.

Orcs also make an appearance in Elder Scrolls: Arena, developed around the same time as Warcraft: Orcs and Humans, though released a year later. It wouldn't be until Morrowind, however, that the Orsimer were made playable. Their in-game description is as follows:

"These sophisticated barbarian beast peoples of the Wrothgarian and Dragontail Mountains are noted for their unshakeable courage in war and their unflinching endurance of hardships. Orc warriors in heavy armor are among the finest front-line troops in the Empire. Most Imperial citizens regard Orc society as rough and cruel, but there is much to admire in their fierce tribal loyalties and generous equality of rank and respect among the sexes."

The trope of Orcs being accepted into society only once having proved their worth to humans as foot soldiers is one we'll look at a little later, too.

Writing for Waypoint, Rowan Kaiser describes Warcraft 3's orc campaign as dealing with "the conflicts between moderation and radicalism, revenge and forgiveness, and dying for freedom or living to fight another day, with Thrall serving as as a cross between Moses and Martin Luther King, Jr." Kaiser is largely - and rightfully - critical of Blizzard's lacking POC representation, but his identification of Warcraft 3 as an outlier even within the studio's own catalogue shows just how different - in video games, at least - its orcish story felt at the time.

While World of Warcraft would continue the story Warcraft 3 established - occasionally relying on various strains of demonic corruption to allow the orcs to fill in their archaic role as destructive antagonists - a few other games popped up afterward that featured the greenskins in a starring role.

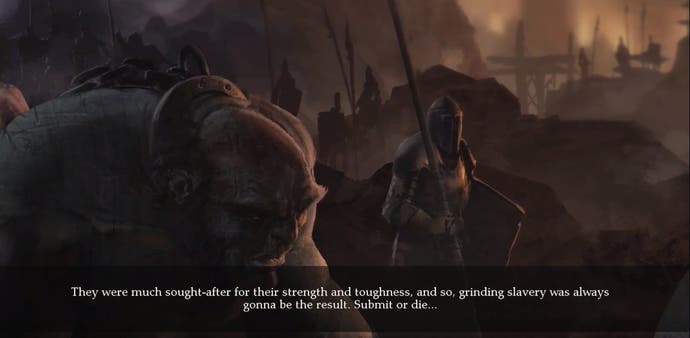

Cyanide Studio's Of Orcs and Men, and spin-off St titles, all featured orcs and goblins as playable characters. In Cyanide's universe, orcs and goblins are persecuted and enslaved by an expansionist human empire. "It's not easy being a Greenskin on this fucking continent," the narrator tells us in the introduction. A similar history of slavery is present in Divinity: Original Sin - although no orcs appear in its sequel.

And then we come to Shadow of Mordor, right back to Tolkien's orcs, 12 years after Thrall woke from his nightmare and set out to unite his people.

As a lover of both orcs and procedural storytelling, the Nemesis system - Mordor's AI memory that has orcs building up personal vendettas against the player over tens of hours of play - is still my favourite mechanic in recent memory. Orcs are more than just fodder in Monolith's open-world - they're the crux around which the whole game revolves.

They are the stars of the show, and yet, are strangely absent from its story in any meaningful sense. With the Nemesis system, Tolkien's orcs were granted a digital facsimile of more agency than they'd ever had before. With it, they were confined back in chains forged from the old tropes. Writing for Paste, Austin Walker observed how the wraith Celebrimbor's description of the orcs as "vile, savage beasts" was, in effect "imperialism dressed up as spirited determination".

The sequel, Shadow of War, expanded its protagonist's skillset to grant the ability to mentally enslave the orcish denizens of Mordor. For some critics, the game rewarding you for breaking the spirits of orcs like "brood mares and racing horses" was the line past which they no longer felt comfortable playing. Cameron Kunzelman, writing for Polygon, grants that Celebrimbor's heel turn does attempt to critique his cruelty towards the orcs - but the game's mechanics are still too firmly rooted in rewarding the player for the same cruelty to make this critique effective.

"Whether you buy the real-world race implications of the depictions of orcs or not, the logic of real-world racism is clearly being referenced in how Celebrimbor justifies the enslavement of orcs and trolls," says Kunzelman, "he sees them as half-people at best, and above all understands them as a resource to be harnessed in competition with his enemy."

At the start of this piece, I suggested that we might look at orcs as the fantasy genre's counterculture. Perpetual outsiders, misunderstood by the haughty, self-righteous realms of men. This is where things get uncomfortable, though. If orcs are portrayed as evil, an abomination, or - in Tolkien's case - a twisted, ugly mockery of a fey, beautiful and noble race, - what does that say about outsiders?

"Kinda-sorta-people, who aren't worthy of even the most basic moral considerations, like the right to exist," writes the sci-fi and fantasy author N.K Jemisin in a 2013 blog post The Unbearable Baggage of Orcing. "Only way to deal with them is to control them utterly a la slavery, or wipe them all out. Huh. Sounds familiar."

I found the N.K Jemisin quote - and an erudite and comprehensive argument to why the history of orcs is inexorable from British imperial racism - in a two part essay by game designer and cultural consultant James Mendez Hodes called Orcs, Britons, and the Martial Race Myth. In the piece, Mendez Hodes traces Tolkien's inspiration for the orcs back to Attila the Hun and the Mongols, through the sinophobic 'Yellow Peril'. It's a compelling and thoroughly researched argument to why we shouldn't downplay the significance of Tolkien's description of his orcs as "degraded and repulsive versions of the (to Europeans) least lovely Mongol-types" - and why even the term 'degraded' has roots in harmful, nonsensical race-science.

Even the idea of a warrior 'race', argues Mendez Hodes, is deeply rooted in the British Imperial concept of 'Martial Races'. A designation created by the British Raj after the Indian Rebellion of 1857, to identify warlike 'castes' from which to recruit for service in the colonial army. The British colonial powers viewed such peoples as:

"... strong, tough, savage. Born into violent, warlike cultures. Raised to prize military prowess above all other pursuits. Naturally inclined to raid their neighbors or, when no neighbors can be found, to fight amongst themselves. Stubborn and simple-minded, despite all their martial skill. Easily controlled by more graceful, cerebral people..."

Which might sound familiar, if you've been paying attention.

"I learned of orcs when a friend showed me Warcraft: Orcs & Humans in 1996, then was disappointed they didn't look like jacked badasses in illustrations from Lord of the Rings and Dungeons & Dragons," Mendez Hodes tells me over email.

"When Blizzard Entertainment announced Warcraft Adventures: Lord of the Clans, I lit up. A story about an orc named Thrall who grew up in bondage to European humans, but rises to become warchief of the Horde? This tiny Filipino was here for it. I was sad they cancelled it, but thrilled when Warcraft 3: Reign of Chaos picked up on Thrall's story."

While the first two games villainised the orcs, Mendez Hodes tells me Warcraft 3 "made Horde species feel like people with voices and cultures".

Their design, unfortunately, was still rooted to those old noble savage and martial race tropes.

"If I tried to list all the Indigenous, Asian and African stereotypes and misrepresentations on the Horde unit and spell lists - or their antecedents and descendants in the Diablo series, for that matter - we'd be here all night. For instance, there's a good deal of the Horde in Diablo's kindest and most offensive character, Carl Lumbly and Erica Luttrell's Witch Doctor.

"The problem with positive stereotypes is that when you're starving for any positive representation at all, they're intoxicating..."

Mendez Hodes brings up Grom Hellscream's redemption arc in Warcraft 3 as "proof that evil is a choice and not a racial trait for orcs, [it] resonates with all the times I've felt tempted to embody a stereotype to seize a momentary advantage in a hostile world".

"So many of our first heroes were queer-coded and disabled villains, stereotypical karate guys, jive-talking gangsters and criminals. Sometimes we were too young to know the ways they hurt us. Other times we knew - because even if we didn't at first, the other kids made sure we found out - but we took them into our hearts like they were wayward relatives. If nothing else, unconscious bias ensured we felt the Horde were our own."

I ask Mendez Hodes if he feels Warcraft 3's sea change was a positive step, all things considered.

"I'm glad Warcraft 3 happened. I think we needed to move through that phase, to iterate on it, to get where I want orcs to go. "

Mendez Hodes learned a lot from Warcraft 3, he says. The relationship between fantasy and culture. How to maintain the cognitive dissonance necessary to recognise the same work can both help, and harm, his cause and identity.

"Tomorrow morning, I'm gonna make coffee and play Reforged, and fall in love with Thrall and all my problematic faves all over again."

At the end of Mendez Hodes' essay, he sets out some thoughts on reclaiming orcs from Tolkien's legacy by humanising and personifying them across fiction, role playing and video games. I wanted to end this one on a positive note, so I spoke to some creators that have been doing just that.

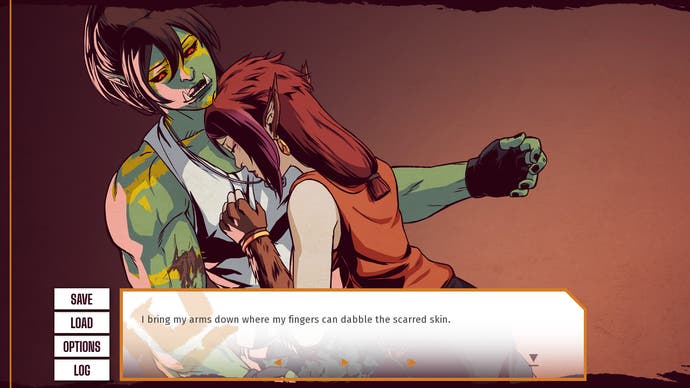

Developer Bitter Berries describes Salting the Earth as a modern-fantasy that takes place in a post civil-war world, focusing on sex-positive LGBT+ themes, and femininity: friendship, motherhood and sisterhood.

"Orcs are often portrayed as ugly, muscle-headed and patriarchal in mainstream media," Bitter Berries tells me over email.

"And at the same time, women with tall and muscular builds were more likely put in the minor roles of villains, perhaps due to their appearances being the opposite of mainstream's understanding of femininity."

Salting the Earth's universe is populated by Orogans - borrowed from 'Orog', Forgotten Realm's taller, smarter Underdark orcs.

"The project attempted to subvert the usual tropes, giving the physically dominant women more complex personalities and a variety of roles, and to make them 'sexy'. Personally, quirky and powerful women really appeal to me.

"Instead of primitivism, the culture of the orcs in the game was inspired by me and my friends' South East Asian cultures. While racism isn't the main theme, there's a hierarchy within the orcs in the game based on the colour of their skin."

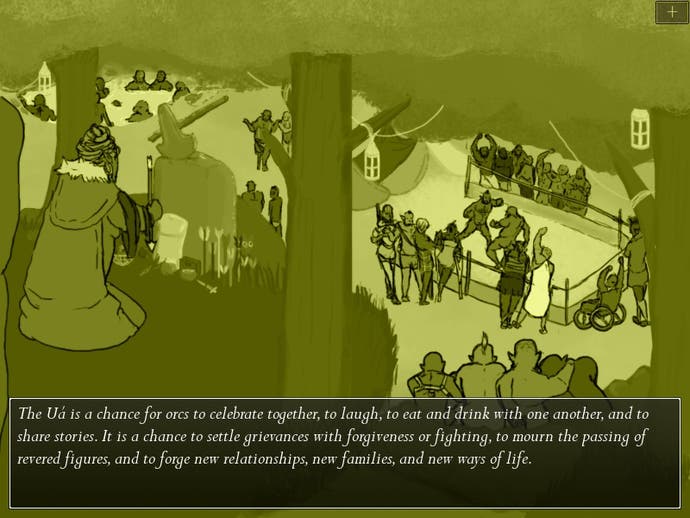

Tusks is a visual novel where the players joins a band of queer orcs at a festival and travels together through what creator Mitch Alexander describes as a "semi-mythical Scotland".

"Most of the ideas that are explored with relation to orcish life in the game - community, history, found family, sexuality, power, social status - are also massively relevant to queer people, and they're derived from my experiences as a queer man."

Alexander came up with the concept for Tusks while playing Skyrim as an Orsimer who, he figured, was trying to unite Orsimer throughout the land, to come together and build their own "wee queer orc stronghold".

Alexander also wanted to reflect his home country in the game.

"Orcs make a very good stand-in for things like folklore and myth about faeries, selkies, goblins and elves in Scotland, as though these creatures may be in some way synonymous or related to the orcs from Tusks."

When thinking about the history of orcs, Alexander considered not just portrayals of race, but also gender and sexuality.

"There's a lot you have to reckon with if you want to reduce the amount of harmful tropes being employed in depicting orcs... they're often described or depicted in racist, imperialist or essentialist ways that feel like it's been written by some 19th Century British head-size-measurer. There are few depictions of orc women in the media, and when they are, they're conventionally attractive human women who are green; the only consideration of queerness you get in orc worldbuilding tends to be one-off jokes."

Tusks, says Alexander, was an opportunity for him to explore themes like found family, community, polyamory, sexuality and power dynamics. As much as it allowed him to subvert orcs, it presented a chance to use orcs to challenge how we think about things in our own lives. With so many people made to feel inhuman, or monstrous, Alexander says, it can be useful for artists to play with and reclaim these ideas for themselves.

"If we're interested in worldbuilding and having something interesting to say in our media, it's a hard sell to then claim the way we depict and portray non-humans doesn't really matter or isn't worth exploring."