I Know It's Over

Anti-climax in Speccyville.

Tremendous Climax

The achievement of victory wasn't always a cue for despondency. Even with frighteningly limited resources at their disposal, a few games got it right. Or, at least, in the context of such lacklustre competition, they stood out as slightly different.

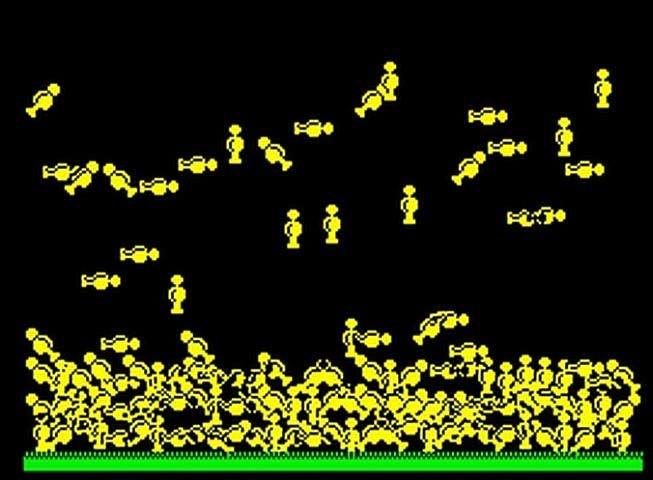

It didn't take much to leave a positive impression, demonstrating just how lazy many other titles had been when it came to lowering a stylish curtain on their contents. Herbert's Dummy Run (Mikro-Gen, 1985) flooded the screen with delicious jelly babies - a sweet, fitting finale to coax a smile from even the bitterest lips. Unless said lips are allergic to E-numbers and balloon up to botox-calamity sizes when they come into contact with baby-shaped candy.

Impossible Mission (US Gold, 1985), whilst also not offering anything particularly outlandish, is a personal favourite. Just before a bog-standard Mission Accomplished message, the splendidly named Elvin Atombender is depicted in a state of extreme displeasure at the player's success. To the extent that (on the Spectrum at least) his face is as red as Cold War Russia. His desperate cry of NO!!! only adds to the fun. Plus, he has a very silly moustache.

In the actually-pretty-misogynistic-but-decent-if-you-were-a-teenaged-boy-and-could-squint-a-bit category (not a huge category, admittedly), Captain Blood (Exxos, 1988) was the fruity French master. An alternative ending resulted in a busty magenta lovely draping herself across the spaceship dashboard and firing off the Captain's rocket. Or some other lame innuendo of that nature.

However, one Spectrum ending sequence surpasses all others. Probably seen only by those with access to POKEs (or, these days, the internet), it nonetheless echoes through the ages like Michelangelo's David, or Rodin's The Kiss. Yes, it's the lavatory larks at the close of the one and only Jet Set Willy (Software Projects, 1984). Having collected every piece of silverware in the mansion, Miner Willy celebrates by rushing back to the first screen and shoving his head down the toilet in a daring and tear-jerking recreation of the game's cover art. Fantastic stuff.

Flushed With Success

Of course, it was trickier for our 8-bit friends to successfully round off a story. Early games struggled because few were able to feature a complex, arching plot in the first place. Text adventures are the clear exception here, but these relied heavily on player imagination and remain closer in spirit to novels. Due to a paucity of hardware resources, character development in sprite-based titles was minimal - or far slower, at least. It took Dizzy a handful of releases and several years before his backstory and Yolk Folk comrades were fully introduced.

What they lacked in plot, classic 8-bit games made up for with accessible thrills and (certainly for the time) straightforward, creative dynamics. Even their basic ending archetypes may have felt more acceptable in an age before comparatively modern examples like Grim Fandango showed that game endings could compete with the best of cinema.

Nor has the curse of the poor ending been overcome. Time pressures and careless storytelling will survive in any creative process. Technology now allows greater scope and, hypothetically, greater freedom; presenting just as many chances for a narrative to fail as to succeed.

INT. BEDROOM - DAYBREAK

A devilishly handsome Eurogamer contributor awakes. He yawns and stretches.

CONTRIBUTOR: What a weird dream, I was writing a ...

Devlishly handsome Eurogamer contributor is silenced by a punch from his suddenly-materialising Future Self. Who is also a replicant. And a woman. And a ghost all along.

FUTURE SELF: Phew, that was close. Hang on, what's this note?

"Congratulations, you've finished reading the feature."

ALL: Oh dear.