How the PlayStation helped Square Enix achieve its cinematic ambitions for Final Fantasy 7 and beyond

Head in the Cloud.

"When I was still in my 20s and had only just entered the games industry," Final Fantasy series producer Yoshinori Kitase tells me, "I was playing Final Fantasy at home with my father sat next to me watching. His impression of the game was that he had no idea what was supposed to be happening on screen."

That's understandable. For those of us who grew up playing video games, their idiosyncrasies have become normalised. But for others, video games present a world that feels alien (sometimes literally) and hard to comprehend. That was especially true in its infancy.

As Kitase explains: "The way games depicted things with 2D pixel art actually used a lot of stylized conventions that only worked within that medium, and gamers had become used to them over time. However, people of my father’s generation who had not experienced games before could not easily understand these.

"I personally want games to be something that anyone from any generation in any country around the world can enjoy, just like film and TV dramas."

The Final Fantasy series has always been focused on dramatic, perhaps even cinematic, storytelling. But it wasn't until Squaresoft (as it was at the time) shifted from its then-home on Nintendo's SNES to the more technically proficient Sony PlayStation console and its CD ROMs, that the company was able to truly achieve its storytelling ambitions. 3D graphics! Full-motion videos! It was all possible at last.

"The Final Fantasy series had always treated dramatic storytelling as important," says Kitase. The first six games all used a flat, 2D pixel art style, but to advance the series Kitase felt "a visual style with a sense of depth was needed to effectively convey that drama."

He cites Final Fantasy 5 - the first in the series he worked on - as an example of simulating a 3D effect by scrolling multiple background layers. Indeed, the SNES became famous for its Mode 7 graphics mode used to create depth, which can be seen in the likes of Super Mario Kart's racing tracks and the scrolling overworld exploration in Final Fantasy 6. But this was the limit of the SNES's capabilities and, for Squaresoft's next Final Fantasy game, it wasn't enough. It needed true 3D capabilities. It needed the PlayStation.

It's well-documented how Nintendo's decision to stick with cartridges for the N64 (following the fallout between Nintendo and Sony (and later Philips) over a failed disc-based console) led to Squaresoft shifting allegiance. Yet this move would prove monumental for the series as a whole: despite originally making its name on Nintendo consoles, the success of Final Fantasy 7 would henceforth cement its status as being synonymous with PlayStation.

"With Final Fantasy 7, the PS1 graphics chip finally allowed me to use the kind of cinematic presentation that had been my ideal all along," says Kitase. "We needed a style of visual depiction that would naturally be accepted like a film is, and it was the PS1 that made that possible for the first time."

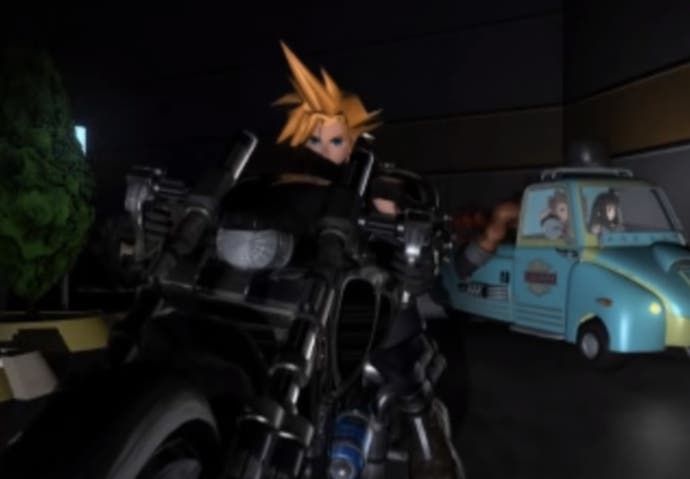

A big part of that was the use of full-motion videos, or FMVs. Rather than using in-game graphics, the team chose to realise major story beats using pre-rendered graphics. Protagonist Cloud escaping from the Shinra corporation building on a motorbike is one particularly memorable sequence, as is a certain upsetting moment halfway through the game. But these scenes were only possible thanks to the extra storage space of the PS1's CD ROMs.

"We needed a style of visual depiction that would naturally be accepted like a film is, and it was the PS1 that made that possible for the first time."

"We saw FMV was very important from the beginning of development, and it was actually one of the big reasons why we picked the PS1 with its CD ROM drive to develop the game on," says Kitase.

FMV had previously been used on home consoles for shoddy interactive games or short intro sequences, but it's clear Squaresoft saw great potential for cinematic storytelling. What really heightened this effect, though, was the seamless integration of FMVs, making Final Fantasy 7 really feel like a playable film. "Up until then, FMV sequences and gameplay had usually been separated, which really obstructed the immersion and anticipation for the player," says Kitase, noting most times it was used, the screen would just black out to move on to the next scene. "However, for Final Fantasy 7 we deliberately did not insert blackouts when moving from FMV to gameplay and took care to tie them together seamlessly to avoid reducing the immersion."

One particular example of this is the game's iconic opening. The camera swirls over a starry sky before cutting to a mysterious young woman as high string notes are held like a pause of breath. The camera swoops back to reveal a vast futuristic metropolis as the music soars, plumes of sickly green smoke spurting into the night sky. Then we fall back in, cut with shots of a moving train, before our spiky-haired hero Cloud leaps off the vehicle and the opening mission begins, with control in the hands of players. This scene wasn't just important to establish the tone of the game, it was the first time players had seen a Final Fantasy world rendered in 3D graphics. The main inspiration was Ridley Scott's famous Blade Runner.

"We were inspired by the overwhelming impact that the opening scene of the film Blade Runner has, where you see a near-future Los Angeles from the air and tried to come up with an idea for our opening to show off the city of Midgar in an appealing way," says Kitase. "However, just doing that would be no more than a simple imitation. One advantage that we had over cinema as a game was the ability for the player to control a character and actually enter into that world. By having the camera zoom in rapidly from the wider cityscape to the train and then seamlessly transition to Cloud jumping off at the platform and becoming controllable, we depicted the scale and presence of the city itself, as well as immersing the player directly into that world."

He continues: "This scene is a great example to illustrate the seamless transitions between FMV and gameplay and the engineers spent several months overcoming difficult technical problems to achieve it. Once this scene was completed though, I was confident that the game would go on to be a success."

He was right. Final Fantasy 7 became the second best-selling game on the PlayStation, not only re-establishing the series on a global scale but establishing the console as the place for Japanese RPGs. Those sales were aided by a marketing campaign that emphasised the game's cinematic highs, utilising its FMVs and noting the "most anticipated, epic adventure of the year will never come to a theatre near you". Finally, Squaresoft seemed to be saying, games could tell stories just as well as films - if not better.

In fact, that comparison was made stark with the release of the first Final Fantasy film, Final Fantasy: Spirits Within in 2001 from series creator Hironobu Sakaguchi that famously flopped, as well as the critically-panned Final Fantasy 7 film sequel Advent Children in 2005. Yet even these shaky ventures into film ultimately benefitted the games in the long run. "Our technology for rendering human characters with realistic proportions advanced with Final Fantasy: Spirits Within and that was then incorporated back into the games from Final Fantasy 8 onwards," says Kitase. "The way we depicted action on the gameplay side also evolved from Final Fantasy 7 onwards and that really culminated and came together in Advent Children. In this way, these two separate feedback cycles pushed the evolution of our cinematic expertise."

Kitase believes Final Fantasy 7's visuals were key to its global success, but they weren't the only reason. "I think that the big factor was how the new 3DCG visuals allowed for easily understood dramatic depictions that resonated with a majority of people from all countries and generations, whether they were dedicated gamers or not, in the same way that Hollywood films do," he says.

"On the other hand, I also think that the game's setting, with its distinctive religious outlook and concepts like the life of the planet, as well as the Japanese subculture trends seen in the character design, brought a unique taste that was not seen in American or European works at the time."

Of course, flashy visuals are nothing without strong storytelling and here Final Fantasy 7 succeeds, too. Its themes of eco-terrorism and the exploitation of natural resources are as prescient today as ever, resulting in continued relevance with the more recent and ongoing Final Fantasy 7 Remake trilogy. But those themes were originally fuelled by something more personal: experiencing loss.

"Mr. Sakaguchi, the father of Final Fantasy, was actually a proponent of the Gaia theory that the planet itself, as well as all people and animals on it, have a life force in the same way," says Kitase. "This was expressed through the medium of cinema in Final Fantasy: Spirits Within and as a game through Final Fantasy 7. We will all find ourselves faced with the loss of someone dear to us at some point, myself included, and I think that the theme of how we reconcile the memories of our departed loved ones at these times and continue their legacy was one that really stayed with people."

Above all, for Kitase it's the appeal of the characters that has lodged the game so firmly in the hearts of its players. "We still get many fan letters for the characters today, and it makes me want to carefully grow and develop them more in future," he says.

Much of that appeal lies with Cloud. Kitase explains how many RPGs don't let their main character speak in order for them to be a vessel for the player, but that's not the case for the Final Fantasy series. Instead each has its own scripted protagonist as part of a unique story, though that was pushed further in Final Fantasy 7 (spoilers!), thanks to the influence of a classic detective novel.

"With Final Fantasy 7 we took an even bigger step in that direction by having it revealed near the end of the story that the protagonist actually had another separate personality that not even the player was aware of," says Kitase. "This made use of a descriptive storytelling trick like the one in Agatha Christie’s The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, which was a very unusual thing for the gaming scene of the time."

"We still get many fan letters for the characters today, and it makes me want to carefully grow and develop them more in future."

It was this focus on "psychological mystery drama" rather than "the heroic tales of adventure" in previous RPGs that, for Kitase, made Final Fantasy 7 the game that "cemented the series' reputation for drama".

Of course, it's that moment with Aerith that's become most memorable of all, though Kitase says he didn't intentionally include such a shocking scene "out of mischief". Rather, he was simply "very confident about the bonds between characters being an important element when creating drama". That idea - and the experience of Aerith's scene especially - has been infused into the series ever since, helping to deliver key emotional moments. Kitase specifies a certain other scene from Final Fantasy 10 in particular.

Indeed the weight of Aerith's scene hangs heavy over the current Remake trilogy, and specifically in this year's middle installment, Final Fantasy 7 Rebirth. Its director, Naoki Hamaguchi, reminisces on that scene in the original game. "I remember I was playing as a middle school student back then, and that really did hit me," he says, "that scene was just so iconic."

While Final Fantasy 6 was the first game Hamaguchi played that really affirmed the power of games to him, it was Final Fantasy 7 that "made me feel that this isn't a movie, this isn't a film, but it can provide a similar kind of dramatic storytelling and entertainment", he says. It's these two games that influenced his decision to become a game creator.

He adds, as the director of the Remake trilogy, "to be able to influence the future of that project, it feels like fate" and while there is pressure to bear the weight of responsibility for the recreation of such a beloved game, "I really feel an enjoyment and a passion for what I do and that overshadows the pressure".

For Hamaguchi, he compares the success of the Final Fantasy series to the likes of Star Wars and The Matrix, praising its ability to utilise the new technology of the day. "They were the first to do something well and do something that's never been done before, because of that [advancement] in the technology," he says.

"Why I think it has remained so well loved and so popular for 20-30 years, is because it was obviously the first big RPG to use a 3D world like that on the PlayStation," he continues. "And it didn't just use 3D graphics, it was the first time we actually saw a game which had that level of depth: going into a world and showing the relationships between characters on a journey. You can't really separate it from the developments in technology at that point in time."

"You can't really separate it from the developments in technology at that point in time."

The same, really, could be said for the Final Fantasy 7 Remake trilogy. The two games so far have reimagined the story of the original and realised its world with current PS5 technology in stunning fashion. The expressive character models and elaborate cinematography go beyond the FMVs of the original, while the previously impressive yet now dated pre-rendered backgrounds have been fleshed out into fully explorable 3D towns and cities that fans - and perhaps the original development team - always dreamed of. The archaic flat greens and blues of the original world map have been transformed into some of the most lavish and detailed open environments in recent memory.

As Kitase told me in a previous interview: "If a player from the modern generation plays [the original], are they going to get the same emotional reaction and response the original generation of players had 27 years ago when it was current and cutting edge? I don't think they would," he said. "We need to remake the game as a modern game so it can continue to be seen in that light rather than just as an artefact from history."

What's more, these reimagined visuals ensure the game is freshly approachable for a modern audience, bringing further clarity beyond stylised gaming conventions. It's as if now Final Fantasy 7 has become what Kitase always wanted to achieve for his father and, in that sense, its development has truly come full circle.