Her Story makes game narratives personal - and that feels like the future

If only you could talk to the monsters...

Fabula and syuzhet are two words that won't net you any sweet esults if you type them into Her Story's antiquated database, but together they're the smoking gun regardless, and a big part of the reason that this audacious caper works as well as it does. They're entertaining words in their own right, of course, fun to say and fun to deploy in text, but when paired they unlock a lot of the magical potential of narrative itself - magic that Her Story relies upon to construct its wayward tale.

They're literary terms, fabula meaning the narrative events when laid out in strict chronological order, while syuzhet refers to the arrangement in which those events are actually delivered to the audience, once they've been artfully chopped around to provide optimal impact. Crucially, for a piece of storytelling to really sing, both fabula and syuzhet need to be perfectly constructed - and these days, that can even come down to knowing when a tale has that strange straight-ahead power that means the fabula should be left as it is. F*** you, Soderbergh.

It is the handling of this delicate relationship that makes Her Story such an exhilarating experience, as it essentially passes control of the syuzhet over to the player - or a second layer of syuzhet, anyway, since the pieces you're putting together are already one step removed from the original flow of events by the time you get to them. Even before you start to explore the fascinating, and rather devastating theme of the piece - which I won't spoil here - Her Story's already a riot of beloved literary ideas, in other words, all brought to fresh life as a video game. To work its tricks, the game drops you in front of the desktop of a mid-90s computer terminal and allows you to poke through the scrambled remains of a series of interviews that took place over 20 years ago - but it does not grant access to the chronological timeline of the original interviews. Instead, you can search for keywords that will call forth specific clips, and these will assert their own non-linear order to the story. Depending on the keywords you choose, you will get the truth - which is particularly problematic here in the first place - delivered in any number of ways.

The gameiest thing in Her Story is a kind of database tracker tool that shows you the correct arrangement of clips by highlighting the ones you have already seen, but that still offers no option to work through the whole selection from the very start. Part of the brilliance of this unusual structural conceit is the way that it defies your attempts to cheat. You'd think that the optimal way to get to the truth, for example, would be to focus on trying to hunt down the clips that lurk at the far end of the database, as they'll contain the final interviews. Such an approach is possible. And yet, while these clips will certainly offer revelations, the nature of Her Story is that the revelations themselves ultimately work by shedding new light on earlier clips and earlier revelations. The power of the narrative is cumulative, so even though it's possible to stumble onto a major twist in your very first search of the database, the true impact will only sink in later.

Her Story is one of those games, in other words, that feels like it contains a little bit of the future. It invokes the past, of course, both in its mid-90s references and in the FMV aesthetics, but its searchable, hypertextual jumbling of its own narrative feels unique and timely and eminently nickable. As does the fact that simply putting the story together is enough here: most of the play that takes place in Her Story happens in your own head as you reconstruct the events and try to interpret them.

There is a freedom in Her Story, and it is the freedom that comes from the game getting out of the way: you don't have to arrange your thoughts for the computer to then check at the end. You don't have to show your workings. It's not Cluedo. You don't actually have to arrange your thoughts at all. Ultimately, the game's about prejudice as much as detective work; it's not Her Story but Your Story as you weigh the evidence and apportion motives as you see fit. There is a neat thematic reason for all of this, I suspect, just as there is a neat thematic reason that the logo on the opening screen fades in and then slowly fades out again, one letter at a time. A narrative can never belong to a single person for very long. Once we become historical artefacts, we belong to everyone, our agency is steadily erased, and our actions are open to everyone's interpretation - or lost for good.

For all its cutting-edge ideas - and aside from the fact that it's that rare cultural object that tackles gender by encouraging empathy as it builds and then dismantles stereotypes - what's truly satisfying about Her Story is that it feels like it is part of a wider trend: of games that are delivered directly through their most personal elements, of games that work like dialogues - even if they can initially look like monologues.

It's not entirely alone, then. In between the moments I've been playing detective in Her Story, I've also been giving a desperate, beleaguered man some incredibly bad advice. I've told him, despite his weakened state, that he should go climb a mountain - and so he broke his leg and died. I told him to sleep rough in the cold desert night and he froze. Just now, I suggested he might like to bunk down next to a nuclear reactor. I am essentially the worst thing that ever happened to him.

The man in question is Taylor, and he's a young, rather studious fellow who has had the misfortune to crash his spaceship on a desert moon orbiting a sun called Tau Ceti. He's then had the greater misfortune of radioing for help and finding me on the other end of the connection. This is Lifeline, a game written by Dave Justus. I think it's designed for the Apple Watch, but it works just peachy on my 4S, although the text is tiny. It's interesting stuff, Lifeline. Since it's designed to slot its interactions into scattered glances at a watch face, it plays out over the course of a few days as little bursts of text. Taylor tells me what he's facing and I pitch in where I can. Sometimes I send him off to reach a distant point and he's gone for hours in real time. Sometimes he asks me to Google something for him - like whether or not you should sleep under a nuclear reactor - and then waits while I do so. It's a game that's almost about building a relationship. But here's the thing: that relationship we're almost building is really starting to sour.

That's been my great revelation as far as Lifeline is concerned: I don't like Taylor, and that's fine. I think he bangs on about science too much, and I think he's too cheery in the face of a hideous disaster. No, it's not the cheeriness, because I'm pretty chirpy myself. It's that he doesn't seem to have really engaged with the situation he's in and so his cheeriness seems inane. Also, I can tell from the stuff he says that he thinks he is cute and funny. If the game was written in the colloquial English voice, he would have said, "I'm mad, me," by now.

I like this idea, of games that unfold as a sort of growing relationship, where their humanity brings your own humanity into play, even if that humanity is sometimes expressed through irritation or irrationality. It's there in Lifeline, and it's there in Her Story. With the player separated from the game's subject by two decades, it's still essentially a conversation that's taking place through Her Story's archive terminal. As I pick my way through the recorded testimony by choosing promising keywords, I'm forming questions, and monitoring the reactions that my questions create. While we're on this topic, the same sense of a chatty sort of back-and-forth is there in Life is Strange, too. Dontnod's fascination with changing the past on an entirely domestic level for the most part turns the whole thing into a controlled form of fanfiction, a shipping of beloved characters that mirrors the way that fanfiction itself often feels like an attempt to create a dialogue with a favourite TV show or band.

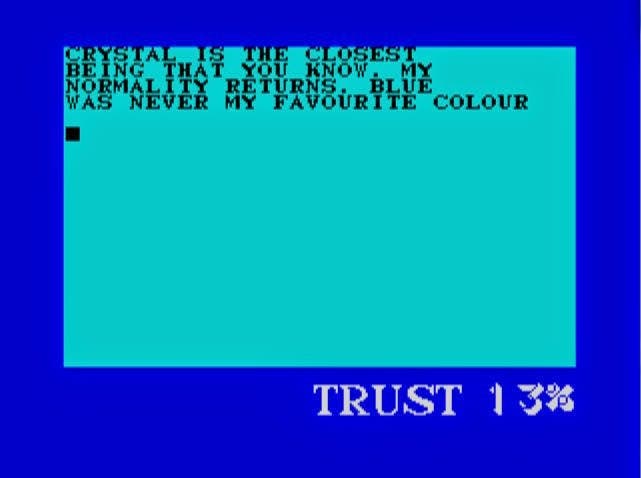

is this new? In a way, it's been around for some time, in the intimacy of Twine games, and all the way back to iD, by Mel Croucher, an old Speccy title in which you had to win the trust of an entity inside your computer by asking it things and telling it things. Maybe it even goes back to the Turing Test, which I have been told, by those who know much more about these things than I do, is now a relatively outdated form of appraising AI because it encourages mimicry above all else. It's still a decent game that computer scientists around the world delight in playing, regardless. Can you create a program that responds to conversational gambits in the way that a human might, to the extent that you can then trick a real human on the other side of the screen into thinking it isn't a program?

Maybe all conversations are a bit of a game anyway. If you've ever handed a young child an iPhone for them to play around with on a bus journey - and yes, you probably shouldn't be doing that and I'm sorry - you'll likely know that the video game that many children love the most, in the years before they discover Minecraft, isn't really a video game at all. It's Siri, Apple's cheery but rather inane personal assistant who will attempt to respond to almost anything my 22-month-old daughter excitedly babbles at it, even though it's clearly flummoxed by her nonsensical requests and desperately just wants the kid to pencil in some squash lessons or book a taxi. Possibly, by the time my daughter grows up and can ask better questions, the games around her will be able to provide more satisfying answers than Siri can. Her Story and its close relations suggest that we're on the right track.