Hearts and Minds

Why the games industry could learn something from WWE All Stars.

"People expected me to come in and Cena to beat me and that would be the end of the Sheamus story, and it was time for someone else to take on Cena. But it was amazing, fella. Probably one of the best nights of my life. I was pinching myself for a long time after that."

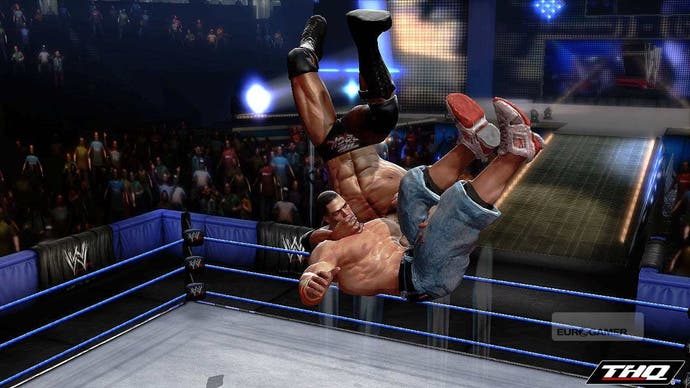

If it all sounds very silly, it probably is. My favourite moment reviewing WWE All Stars was when I first took control of Randy Orton - an Adonis clad in viper tattoos - and knocked out an online opponent with his signature RKO. This involves suddenly spinning round, grabbing the other guy's head over your shoulder and dropping to the canvas.

The move is mainly memorable to me because I was practically miming it in my lounge with the Xbox pad and in the course of pulling it off, I broke a plate. (As the WWE says: "Don't try this.")

Meanwhile, my favourite moment at this year's WrestleMania - the pinnacle of the pay-per-view schedule - was when Stone Cold Steve Austin did a Stone Cold Stunner on Booker T at the end of a match, for no reason at all.

Sitting at the Hall of Fame event after the wrestlers have finished their press interviews (which they all visibly enjoy, especially Sheamus, who seems delighted to have some people "from back home" to pal around with), it seems like the games industry could learn a lot from WWE.

At its heart, the company built by infamous chairman Vince McMahon is a rickety enterprise. It is losing market share and smothered by increasingly garish advertising.

I've argued before that the success of hardcore video games like Call of Duty is illusive too, and that if you ignore outliers like COD and Grand Theft Auto, the middle ground is now a much harder place to recover your development capital.

Gaming still needs to find an answer to this. Because as the likes of Guitar Hero have proven in recent years, even extraordinarily successful brands are vulnerable to collapse in a short space of time. With every reboot and rehash, consumers are pushed further away from what once engaged them, and it matters less and less.

It's tempting to say WWE has the same problem now. That it's too dependent on expiring heroes to bring in the big bucks. The fans may have loved seeing The Rock, Steve Austin and The Undertaker as the main attractions in Atlanta, but perhaps the shareholders didn't.

But that misses the point. WWE is unlikely to fall down any time soon, even if commercial realities eventually adjust its size and shape, precisely because it remembers and respects its past. These are real people, real families - and we really like them. Watch the Hall of Fame ceremony and you know all the talk of WWE's heart is more than metaphorical marketing.

Sheamus may have spent 10 years wrestling his way around dingy venues in Ireland, trying out in sweaty conference halls for talent scouts, before uprooting his whole life to take a punt on a few years' training in Florida. But how he is any different to my friend Max, who worked on first-person shooters in Nottingham for years and shifted his whole life to Seattle to work on the AI in Halo?

Video games can't easily be fronted by real people but they are developed by real people. Apart from a few Fellowships and Halls of Fame, the industry does a poor job of keeping more than a couple of dozen of them in view of the public, and often seems more content to do the opposite.

Cody Rhodes told me that he doesn't want to spoil the image he has of his heroes by getting to know them too well. Watching and loving WWE makes me realise I wish I had more gaming heroes to worry about getting to know.

Seeing studios like Bizarre Creations - themselves corporate entities, but at least corporate entities with a signature - crumble and fracture makes me realise the number I do have is probably shrinking, even as we're told gaming is bigger than ever.

Hopefully, by the time people like Sheamus have shifted from the Superstar side of the WWE roster to the Legend one, that will no longer be the case.