Have videogames lost the plot?

A look at why games don't tell good stories.

Despite the advances of the past decade, from physics engines and motion control to near photo-realistic graphics, there is one area in which games still have huge scope for improvement. Why, after all this time, are so many videogames still so bad at telling stories?

True, there are more examples of better quality writing to be found these days. More adult themes and activities have crept into titles like Heavy Rain. But there's no escaping the fact that for the most part, most games have about as much narrative sophistication as a Choose Your Own Adventure book.

Scripts, voice acting and the range of choices available to the player have all improved, while open-world games offer a sense of freedom which exists outside of the boundaries of plot arcs. Yet in some ways, these advances serve only to highlight the jarring nature of what happens when you are funnelled into pre-scripted paths.

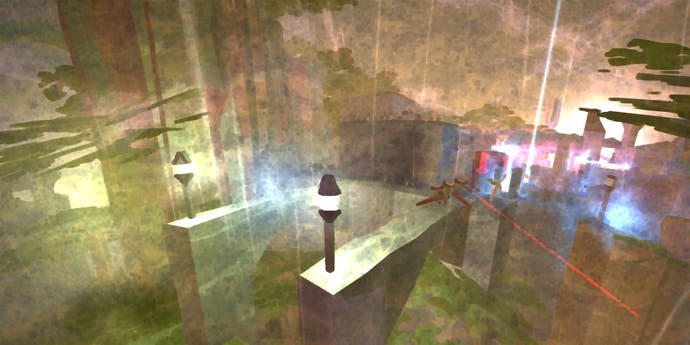

Why is this? Will it ever be possible to play a game with causality, where you can truly affect the outcome of a story? Eskil Steenberg, the solo developer behind the innovative first-person MMO Love, certainly thinks so.

"It's already been done, except we don't think about it as story-telling," he explains.

"Take Counter-Strike, for instance. You wouldn't call that a strong story-telling game, but its a game where most of the players have stories from the game. It's a very limited story, which involves mostly bombs and hostages and how many people are left. But they are stories and they are told by gamers."

This concept of players developing their story within a set of rules is known as "emergent narrative". Indie games like Dwarf Fortress, the oft-mentioned Minecraft and Steenberg's own Love are leading the way in this field. By offering up gameworlds you can interact with on a deeper level, they create the potential for dynamic, player-authored storylines.

"The human mind is hard-wired to construct narratives as means of explaining what one experiences in one's real life, when watching a movie, or when playing a game," explains Mark Riedl, an assistant professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology's School of Interactive Computers. He is currently conducting research into intelligent narrative computing.

"But while an experience – in real life or a game – can be compiled into a narrative, there is no guarantee that that narrative will be a 'good' one.

"Emergent narrative is simple to achieve; all you need is a rich environment and a good set of rules with which to simulate the microworld," Riedl continues.

"The alternative, which I refer to as "managed experiences", relies on a storyteller that is looking at the microworld, the player, and future possible narrative trajectories, and attempting to enforce some sort of structure."

Steenberg has adopted a similar approach for Love. "The game itself generates the entire world. The players can build a settlement anywhere in the world, and the AI are independent AI characters," he explains.

"There are five different tribes: they fight the players, they help the players, they do all kinds of things – they act as if they are independent actors. And that creates a story that is very very dynamic and a lot of things can happen."

This strategy is markedly different to the one most developers employ today. "Currently I think that games are kind of depressing," says Steenberg. "If you play the first Zelda game – it's 25 years old, but you can do more things in that game than most games you can play today."

He adds: "That tells me we haven't really gotten very far. The games that are closest are games like Fallout, but they are very scripted. They are sort of brute forcing it. Instead of making a roller-coaster, they're making a roller-coaster with multiple tracks and various places where you can switch tracks."