Pickup where you left off: Returning to Guitar Hero

Golden axe.

Ted Nugent's Stranglehold is a nine-minute beast of a song, a deeply sinister trip to the dark side with a guy who just doesn't know when to quit. The very first line - "Here I come again now, baby / Like a dog in heat" - sets a certain cards-on-table tone. But in addition to its signature juggernaut riff, shred in tooth and claw, Stranglehold also features a long, sparse mid-section powered by a rubber-band bassline. It's during this spooky longueur that the Nuge - or you, if you're playing Guitar Hero World Tour - wrings out odd guitar wails and bursts of distorted squall. It's one of those solos that goes on so long that you almost forget it's part of an actual song, until Ted pops up again, singing hoarsely: "Some people think they gonna die someday / I got news, ya never gotta go." It's an unsettling gospel of everlasting life, preached by a dude who, when he's not generating intensities in ten cities, enjoys shooting flaming arrows. It's also totally brilliant.

Critics like to talk about rock immortality, usually attaching it to the geniuses who leave us too soon: your Hendrixes, your Cobains, your Buckleys. For a while, it looked like the Guitar Hero franchise was going to achieve something comparable - maybe not inventing a brand new genre of rhythm action game, but certainly perfecting and dominating it. The first installment came out at the tail end of 2005 and within 12 months Guitar Hero was a global phenomenon. Five years later, it seemed to simply run out of puff, defeated by the shifting player tastes that also kneecapped its sturdy rival Rock Band. Guitar Hero is dead, essentially, but deserves to be on the cover of Mojo magazine, if only for services to classic rock, introducing a whole new generation to Tom Petty, the Edgar Winter Group and Creedence Clearwater Revival.

But rather than canonising Guitar Hero, anecdotally it feels like former players have a mild sense of embarrassment about all those hours spent doing rock karoake, as if it represented something faddish and ephemeral like collecting Pogs or nursemaiding Tamagotchi. It probably didn't help that the game arrived so perfectly formed, so sui generis, that (subsequent addition of drums and vocals aside) there really wasn't anywhere for it to go. But did we all just stop enjoying it? Was there a moment where, collectively, we looked at the make-believe guitars leaning against our sleek home entertainment centres and thought, in the immortal words of Mark Knopfler, "that ain't working"?

I was an early adopter, though initially sceptical of the original Guitar Hero controller, with its Opal Fruit fret buttons and kindergarten-ready robustness. But when the penny dropped, when you worked out the causal relationship between the endless highway of blobs on-screen, your colour-coded fret control and the rhythmic clicking of the strum bar, it felt something close to sublime, the deeply satisfying completion of a cosmic circuit. For some players, the joy seemed to be performative, an opportunity to live out a cherished rock fantasy by windmilling the axe like Townshend or caressing and worshipping it like Slash. My enjoyment was more results-orientated - strapping the guitar up high on the chest, left hand clawed round the neck, frowning with concentration rather than gurning with fake ecstasy. Despite my aggravated expression, I loved the game.

My Guitar Hero wobble came during its transition from PS2 to PS3 and Xbox 360 - the prospect of shelling out £30 for another controller was singularly unappealing. Eventually, I picked up a cheap overstocked guitar bundle of the wildly unpopular Aerosmith standalone game, but some crucial momentum had been lost. I never quite got up to speed with next-gen Guitar Hero. (It didn't help that the Aerosmith game was particularly thin gruel.) Those dinky guitars were excommunicated to a cupboard where they stayed, accumulating dust, until a month ago, when Guitar Hero World Tour plopped through my letterbox.

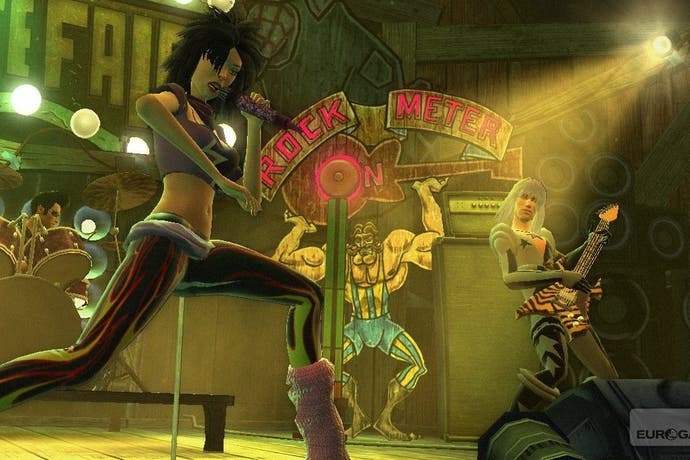

I rooted out my Aerosmith-faceplated guitar and, after a lengthier rummage, the wireless dongle shaped like an oversized plectrum. World Tour is essentially Guitar Hero 4, the installment where the franchise belatedly expanded to include drums and vocals. I had no interest in that side of the game, or the suite of music creation features, or even the extensive possibilities of avatar customisation. I just wanted to get back in the zone, that place where I was once able to get to the end of Bark At The Moon even on Extreme difficulty.

Stranglehold pops up around halfway through World Tour's bulging career mode, with Ted Nugent himself making a mo-capped cameo, arriving on stage astride a mighty buffalo. That was the moment where various realities - a classic rock song from 1975, a video game from 2008 and a rusty-fingered player in 2015 - all collapsed and snapped into focus. That was the moment I fell in love with Guitar Hero all over again, the sort of complicit, blinding affection that helps you overlook things like your beloved's mystifying obsession with ska and pop-punk. I burned through World Tour in a week on Hard, and have already ordered Guitar Hero 5 after locating an acceptably cheap copy. I'm now eyeing up Guitar Hero: Warriors Of Rock. In this flush of rekindled enthusiasm, it's like unexpectedly discovering there are two extra box-sets of my favourite TV show.

It feels like every week, another band announces they've reformed for a series of comeback shows. Could Guitar Hero do the same? Recently, while deep in the meditative mind state required to rattle through Bob Seger's Hollywood Nights for a five-star rating, I've been thinking about how best to bring the franchise back, so it might effectively compete with Ubisoft's terrifyingly purist Rocksmith, which forces you to play an actual guitar. It might not be to everyone's taste, but I would recommend jettisoning all the gigging fol-de-rol - in World Tour, there's a Tool show where you perform a set of their doomy but satisfyingly complex dirges in a fully abstract realm, essentially a nightmarish horror vortex with a giant Sauron-esque eye occasionally blinking at you.

It's all a bit grimdark, but it makes a refreshing and effective change from the usual rote renderings of cartoonish venues with an oddly synchronised crowd waving their hands in the air. Perhaps the premise of the Guitar Hero reboot could be cosmic: a space capsule containing 100 songs blasted into the unknown, a beacon of humankind's highest artistic accomplishments. The player(s) would be some sort of alien, getting to tentacled grips with this strange new world of power chords and whammy bars against a slowly spiralling backdrop of heartstoppingly beautiful starscapes. It might happen, someday. But in the meantime, why not dig out one of those old plastic guitars for a quick Sunday afternoon gig, your own impromptu Live Lounge? Hand on heart, it's aged a lot better than Tamagotchi.