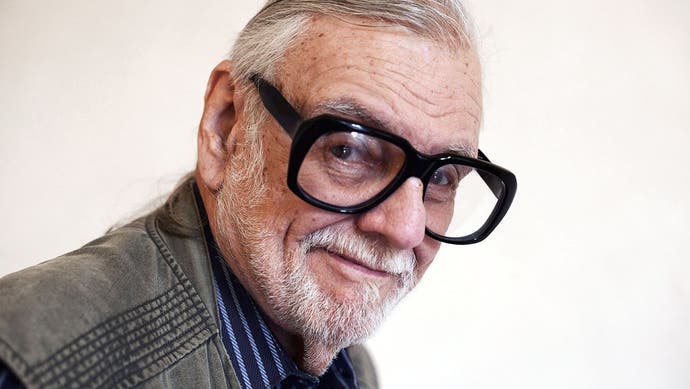

George Romero and the politics of panic

How the master of zombie cinema helped to change gaming forever.

In what seems to be a relentless line of celebrity deaths, the passing of George A. Romero will sadly probably only make waves in the bloodier corners of movie fandom. Yet this quiet, humble and bookish filmmaker, who died on Sunday aged 77 following a mercifully brief battle with lung cancer, was one of the most influential creative minds of the late twentieth century.

That may sound like hyperbole, but only if you consider Romero's legacy to simply be the invention of the modern zombie. That's an accolade that can't really be argued with. Prior to his 1968 debut, Night of the Living Dead, a bleak and grungy primal howl of hopelessness aimed at the guts of an America reeling from Vietnam war stories and civil rights riots, the movie zombie was a creature of Haitian folklore. Arms out, blank faced, these brainwashed voodoo drones were essentially supernatural henchmen. In Romero's hands, in a movie shot with his friends for just $114,000, they became atavistic allegories for all that was wrong with modern western culture: mindless, ravenous, your friends and neighbours reborn from the grave without empathy or emotion, only insatiable hunger.

Thanks to botched copyrights, Romero made almost nothing from Night of the Living Dead, but parlayed its notoriety into a string of offbeat genre classics. He repeated and refined his signature motif over the years, using zombies to critique vapid consumerism in Dawn of the Dead, and the military-industrial complex in the nihilistically savage Day of the Dead, but he also riffed on feminism in Season of the Witch, rust belt alienation in the hypnotic pseudo-vampire movie Martin and even dystopian Arthurian fantasy in the deeply personal Knightriders (no relation to Hasselhoff's TV show).

The fact that pop culture today is awash with the undead is entirely down to Romero's instinctive and incisive reinvention of the zombie myth. As overplayed as they are, they wouldn't have that staying power if Romero hadn't tapped into something deep and primal: our fear of ourselves.

Only gaming seems to be be more zombie-obsessed than film these days, and someone at Capcom was clearly a Romero fan back when Resident Evil was being developed. That famously cheesy live action cutscene from the start of the original game couldn't wear its Night of the Living Dead influences any more plainly and while the game quickly spirals off into more outlandish territory, those early hours sealed inside a house with shambling flesh-eaters are equally indebted to his work.

Romero even directed the Japanese TV ads for Resident Evil 2 and was lined up to direct the movie adaptation until the studio decided that, despite the huge influence his films had on the games, a more mainstream action approach was needed for cinema audiences. Romero's Resident Evil script can still be found online and reveals a much more horror-driven approach.

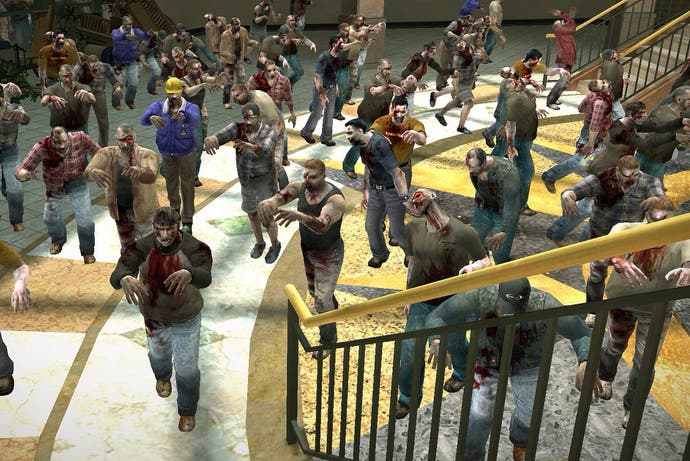

Capcom's later zombie game, Dead Rising, is even more blatant, lifting its mall-survival premise wholesale from Dawn of the Dead. It's not just a recent thing. One of the first ever Ubisoft titles was Zombi, an 8-bit horror adventure that was basically Dawn of the Dead: The Computer Game in all but name.

Those are only the most overt and obvious ways in which Romero influenced gaming, however. There was more to his cinematic output than just gore and ghouls. One of the reasons his work was able to overcome the repulsion and outrage of movie critics - Dawn "pummels the viewer with a series of ever-more-grisly events" sniffed Variety in 1978 - was because there was intelligence behind the splatter. Not just the bluntly obvious satire of Dawn's mall-filling zombies, but in the way Romero used the undead to explore the frailty of human nature at its most desperate.

Each one of his zombie movies is a self-contained petri dish, a microcosm of society trying to get its shit together long enough to survive the unimaginable and often failing. In Night of the Living Dead, it's cowardly Harry, who only wants to seal himself and his family in the cellar and to hell with everyone else. In Dawn of the Dead, it's Stephen, so obsessed with protecting meaningless trinkets that he starts a fight with raiding bikers and dooms their safe haven. In Day of the Dead, both the amoral Dr Logan and overbearing Captain Rhodes doom each other with their myopic views and inability to compromise. Time and time again, pressure brings out our worst nature, not our best.

It's a message that rings true today in gaming. Microsoft's wonky 2013 open-world zombie survival game State of Decay understood it, and was able to overcome the hurdles of its creaky game engine as a result. By asking you to referee between different characters with very different priorities in a world where every step away from sanctuary heightens the risk of death, it put you inside a Romero movie and said "Go on then, see if you can do better".

But the echoes of Romero's morality plays can be found deeper still, not in scripted NPC encounters but live, unpredictable, online play. Remember Call of Duty's first Zombies mode, back at the end of World at War? A small group, desperately trying to fortify a crumbling house to delay the inevitable? That's Night of the Living Dead. With Nazis. When someone did something stupid, leaving your ad-hoc strategy in bloody tatters; when your partner makes an ill-advised dash for ammo in PlayerUnknown's Battlegrounds or H1Z1 and ends up dead for their trouble, leaving you exposed and vulnerable in the process... that's a Romero story, played out in a virtual realm thanks to real human weakness, and it echoes everywhere in this era of co-operative survival multiplayer.

Romero understood that gore and violence only really have meaning when they're seen as the result of hubris or selfishness. It's true that you could swap the zombies in his movies for any number of other threats and still have them work. The siege drama is a tale as old as history itself. Just ask the people of Troy or the Alamo. But Romero gave it a modern face, our face, a literal reflection of our base impulses unleashed, and a reminder that the real threat doesn't come from what's on the other side of the barricade - it comes from the little voice in your head telling you to lone wolf it, and leave the others behind.

George Romero made great movies and reinvented cinematic horror, yes, but he also inadvertently gave us one of gaming's most important moral lessons: griefers never prosper.