Geometry Wars: Retro Evolved retrospective

Here's looking at Euclid.

Wikipedia has just informed me that, back when the Xbox 360 launched in 2005, European early adopters had 16 titles to choose from.

Typically, they're a threadbare bunch. There are sublime entries, of course, like PGR3, and there are endearing botch jobs, like Condemned: Criminal Origins. Then there are the almost-goods, the cash-ins, the make-weights, the disappointments and the straight-up holdovers from the last generation.

Shooters, racers, third-person adventures: Microsoft had you just about covered - as long as you were willing to sacrifice a bit of depth for a bit of... Well, as long as you were willing to sacrifice depth, anyway. The star of the show stands out from the other games on that list, though. The star of the show didn't even come in a box like all the rest, in fact. Instead, it whizzed in through the ether, its code moving at the speed of light. Then it exploded across the screen of your brand new HD TV and - jeepers! - suddenly it felt like the next gen had really arrived.

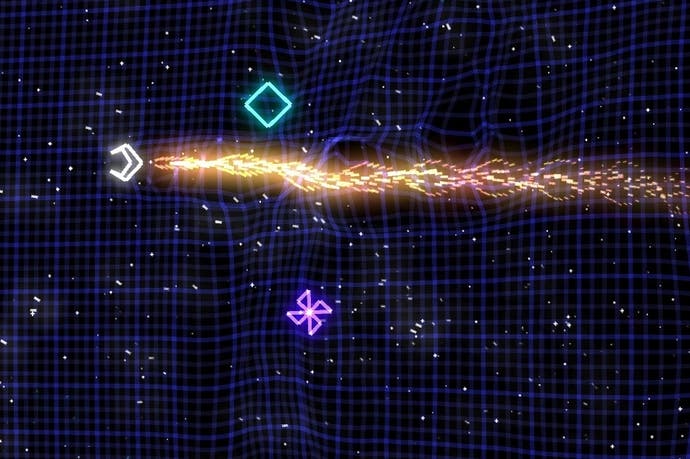

They called it Retro Evolved, and the name could not be any more apt. Geometry Wars builds on glorious ideas pulled out of the early days of the arcades - as a twin-stick shooter, its spiritual father, Robotron 2084, hails from 1982 - but it takes those ideas and gives them something that can only be described as a glitzy bleeding-edged hug.

It doesn't reinvent anything major or toy with the fundamentals too much - one stick to move, one stick to shoot, pour in the enemies and try and stay alive out there - but it brings things screeching into the 21st century nonetheless. It has online leaderboards instead of the old hi-score table, in order to foster a new kind of old kind of community. It has blinding HD lights, thousands of particles and a peerlessly solid frame rate throughout.

And it all makes for an odd mix, really: a game that plays like a classic but feels like it's come from the future. A friend of mine blamed Geometry Wars for the deaths of his first four 360s - ah, Microsoft! - and it's not really that hard to follow his reasoning. Bizarre Creations' tiny game feels powerful. It throbs with unstable energy. It snarls and trembles and spits lightning. It pools and simmers on your HD screen and then it erupts.

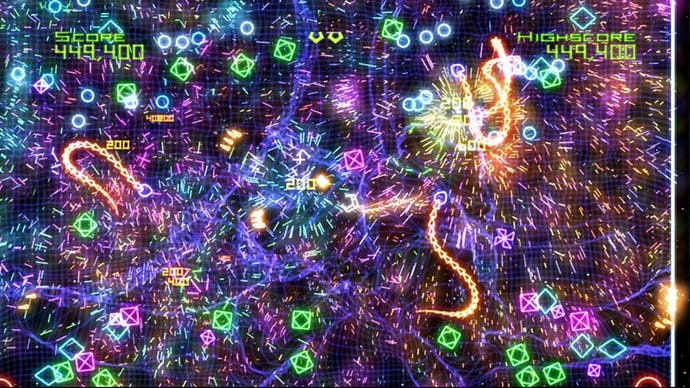

There's plenty to say about the mechanics - about how it uses simple behaviours to create emergent action, while also giving its cast of squares, circles and diamonds a real sense of character. There are no discrete waves here, but the jumbled spawns allow a sense of intelligent pace as you move from the mindless windmills and grunt-like diamonds of the opening moments through to cowardly greens who race away from you and have to be crushed, en masse, against walls, and then the purple dividers, snakes, blood red craft, twinkling confetti storms, and the gravity-bending specter of the well.

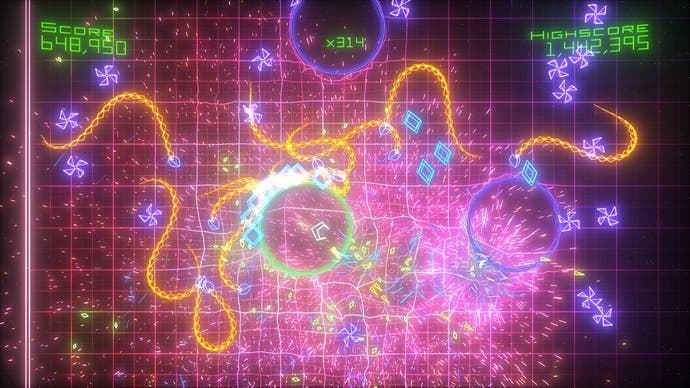

The well! A lone catherine wheel in a game filled with sparklers, that well gives Geometry Wars something twin-sticks are often lacking - a reliable means of constructing a set-piece. Spinning and fizzing with life, they're a gloriously dangerous addition, modifying enemy behaviours as they draw your foes in and eat them, and allowing you a certain degree of control over their eventual eruption depending on how many shots you risk firing their way. Light bends around the little lenses wells create and space elephants moan over the speakers when a smart bomb wipes one out in its prime. It's a mournful sound, and rightly so. You let them get to you. You lost control.

There's plenty to say about the lineage of Geometry Wars, too, of how a treasured aside in Project Gotham 2 finally got its own starring role, and how the series travelled to arguably greater heights with the peerless take-it-all-apart-again approach of Retro Evolved 2. The sequel - it has the unmistakable swagger of a blockbuster - breaks the design into its constituent parts (this feels, inevitably, like Bizarre is reverse-engineering Eugene Jarvis code). It then reconfigures everything as a series of brand new variants, the best of which somehow manages to ditch shooting altogether.

And there's even quite a bit you could say about tactics, although this route leads to madness, or at least to YouTube where the best in the business can score several million points off a single craft. So much room, but it fills up so quickly! Pick away at the swarm, bunch the blue guys together, throw the green guys into the corners, and then start moving in ragged circles - anti-clockwise, I find, fits the game best. Prey on the gravity wells as much as you can, and then actually pray when the snakes come out: invulnerable bodies taking up precious space and luring you to your doom.

Today, though, mere days away from the unveiling of Microsoft's latest machine, let's not forget another crucial part of the Geometry Wars package, though. Let's not forget its lasting impact.

Cast your mind back to those first 16 releases. How many of them set the tone for the generation that followed? Actually, let me clarify that a little: how many of them set the tone in unambiguously positive ways? My very favourite thing about Geometry Wars may ultimately be the fact that so many hallmarks of the current gaming scene's most thrilling development - the sudden ascendence of compact but fiercely creative downloadable games - are already visible here, perfectly formed and easy to spot.

There's the business stuff, of course - digital distribution, a small development team, canny online integration - but there's much more than that too. Although published by a platform holder, Bizarre Creations' shooter perfectly captured the indie spirit that would pervade the next eight years. For a lot of console gamers, it helped set the tone for the future, arguing that new games didn't necessarily have to mean bigger games in the traditional sense.

Games could suddenly be free to turn to the past openly, they were free to be glorious throwbacks that found inspiration in great old ideas (rather than merely clinging desperately to great old licenses, which has always been common but is not, really, the same sort of thing). This would be a generation in which looking backwards would be as much of an option as looking forward - as long as you had the disciplined eyes and the wild mind to find something that felt fresh. You could even leverage the future to reinvent the past, to make it look and feel like the arcade you always wanted - the arcade that shone and glittered in the darkness of your memory.

Games could be shamelessly abstract, eschewing textures and bump-mapping and the eternal pursuit of realism in exchange for a different kind of spectacle - a more fundamentally gamey kind of spectacle. And yes, even as Achievements, oppressive scripting, and five hour campaigns that felt like uninterrupted tutorials ushered in a new era of ingratiation, Geometry Wars said that games were free to be brutally hard again too. There was no foul in killing the player in seconds as long as you gave people the option of a near-instant restart.

More importantly: Geometry Wars' design is playful in the best sense - with no cut-scenes or famous actors doing the voices, it offers the simple joys of allowing you to fiddle with the manner in which its separate pieces work together. Frantic as it is, it fosters a feeling of experimentation and investigation that anyone who's played Minecraft will know all too well. I remember the first time I nudged two wells together and sat back, eager to see what would happen. (I died.) Sure, elsewhere in the launch window, Joanna Dark was following glowing chevrons from one firefight to the next, but that was only one way of doing things. Here, a cutting-edge console game had found the room again to let you just meddle with interactions, to let you learn things for yourself.

And now as a new hardware generation looms, with all the fears and hopes and rumours these times engender, it's worth remembering how gleefully unexpected the triumph of Geometry Wars was. Next Tuesday, in other words, you could try and look at the long game: you could predict the trends, you could hope for the best and you could fear for the worst. As for me, I'll be scouting that launch line-up and hunting for the one game that really gets it. I'll be looking for the one title blessed with Retro Evolved's confidence, with its sense that it's seen the future and discovered it's a place filled with glittering opportunity.