Games of 2012: Thirty Flights of Loving

Forget your past.

At night, the staircase is riddled with cats. They're everywhere: mewling, pacing, slumped in those peculiar elbowy puddles that only cats can form. One of them - my favourite one - walks back and forth along the banister with an imperious tilt to the head. This guy's special, I think. Sure, he's a pale ginger like all the others, but now and then he flashes a luminous, rather lurid, orange.

Over the last few months, I've spent a lot of time with this magical cat. I've watched him, prodded him, tried to figure him out. Is he sending me a message in neat little bursts of colourful morse code? Is he briefly transforming into an interactive object? Is he highlighting something that's buried, something that's only there to be found by cat fans with a worrying amount of free time on their hands?

Eventually, I emailed Brendon Chung, the creator of the cat, and the staircase, and Thirty Flights of Loving, the game that houses them both. He explained that the sudden bright orange flash is down to a quirk of the Quake 2 engine he's been working with: something to do with radiosity and a patch of light that hits the railing the cat stands on. It's not a feature as such, just a bug. Just a bug that looks like a feature.

Goodbye to 2012, then - a truly brilliant year for games. Srsly: we've just had twelve months defined by titles that seemed only to want to outdo each other in terms of their endless, dizzying, sometimes infuriating capacity for sheer playfulness. For me, it's been the year of the Wild Goose Chase, whether it was Dishonored's gloriously threadbare hub-pub, tempting me with hints of an (illusory) secret lurking behind the bricked-in doorways of the third floor, or Fez, sending me back to the notepad - and sometimes off to the internet - to tease out codes that might have been mere patterns, to solve puzzles that often proved nothing more than glittering twills of artistic fancy. Spelunky, Torchlight 2, Whimsyshire in Diablo 3: so many amazing games burying themselves amidst secrets and tricks both real and imagined. None have teased me so much, though, and none have teased me so persistently, as Brendon Chung's tumbling head-over-heels tale of heists, romance, and - I think - betrayal.

This is bit weird, really, because Thirty Flights isn't a game with a huge scope for exploration - at least not in the traditional video game sense of the word. Wrong-headed as it turned out to be, that instance of feline investigation on the staircase was a rare moment of player freedom in what is otherwise one of most audaciously restrictive games ever created. Chung's sequel to the mesmerising and rather debonaire Gravity Bone is fractured but tightly controlled: it's smashed time and space into pieces, but then it's arranged those pieces in careful patterns, like a complex mosaic made from pieces of broken mirror.

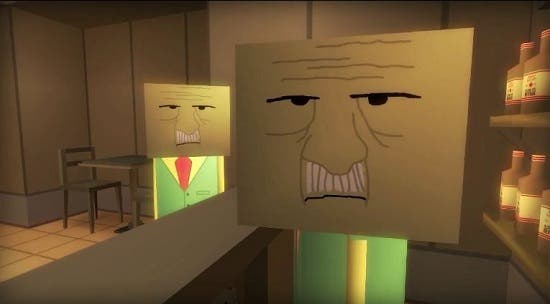

Okay: tiling's probably the wrong metaphor. Instead, let's say that, in an era of often fairly clumsy big-budget cinematic games, Chung's the most assured - and thrifty - of directors. He works with old tech and a deceptively simple block-headed cast, yet he embraces proper filmic editing as you move through his suggestive Technicolor worlds, and then uses his jump cuts to propel you up and down the timeline without ever relinquishing the pace of a headlong pelt. He's fearless in his impatience, arriving late and exiting early, and he excises almost all of Gravity Bone's more, well, gamey mechanics while he's at it, too. There's no platforming, no lock smashing, no poisoning contract jobs enlivened by illicitly donning a waiter's uniform here. There's just the next door, the next corridor. The next schism, the next fugue.

I normally hate oppressively linear video games, with their naff set-pieces, their ham-fisted scripting, their persistent taint of mechanical disloyalty. Why don't I hate this one? Well, here's a lovely piece by Nathan Grayson arguing that Thirty Flights doesn't remove your agency so much as relocate it, bringing you in as a kind of narratological coroner tasked with working out what happened, and what the compacted snarl of plot laid before you meant. You know, how the false passports, the organised criminals, the zero-gravity wedding parties, the obscure subterfuges and the car accidents all fit together, and how the single word “flights” can simultaneously apply to staircases, airplanes, improvised escapes, and Bernoulli's ever-lovin' Principle. I adore this idea, and over the last few weeks, I've been returning to the game and zooming in a little closer. I've settled on one mystery in particular: Who am I?

At the moment, I think Thirty Flights is a game about answering this question above all others, and despite the epidemic of amnesia floating around wherever protagonists are found on consoles and PCs, it's an area that games tend to explore in fairly limited ways. In a lot of games, you're, well, you: an expanded, heroic version of the person you want to be, at any rate. You're the you that emerges after thoughtful placement of your skill runes, your power armour, your paragon points. Equally, other games often give you a sketch of a character, and then provide you with tools - and a little manoeuvring room - to tailor that character until they're broadly who you want them to be. Either way, whether you're building a thrifty, cowardly Commander Shepard who's always lurking behind cover and conserving ammo, say, or if you're unintentionally retconning good ol' Nathan Drake, throwing in additional clumsiness when it comes to the jumping and the shooting, you are a collaboration to a lesser or greater extent: a negotiation between the design and your own in-game behaviour.

Thirty Flights doesn't work that way: it uses its first-person perspective not just to frame the action, but to obscure your role in it. Sit behind the computer monitor, then, and really ponder the person on the other side of the screen. As objectives go, this was all set up in Gravity Bone, where the game ends - spoiler - in a flurry of someone else's memories, and you slowly realise that they're the memories of your character, and that your character is not you, and that his life before you arrived on the scene was pretty much bursting with incident.

In Thirty Flights, the distinction between the you at the keyboard and the you in the midst of the action is much more explicit, though. Once again, you're Citizen Abel, Chung's go-to avatar for weird, suggestive violence and modish skulduggery - but with your own agency curtailed, Abel's agency becomes all the more interesting.

His actions surprise me, frankly, even as I press the keys that allow them to happen. His ingenuity is not mine, his calm under pressure is not anything I recognise or possess. Each context-sensitive prompt is a surprise, whether he's stealing someone's luggage trolley as he flees through an airport with a wounded colleague - and then using it brilliantly to wedge open a falling security gate - or peeling an orange in an abstracted, but still peculiarly brazen act of seduction. Sure, like Nathan Drake, he's a defined character, but here I don't even have the limited control given in Naughty Dog games to prioritise threats and to fumble platforming sections. I can't die. I can't break stuff.

Perhaps this sounds sort of awful, but Thirty Flights is that one-in-a-million game that renders an awful prospect magnificent. Instead of frustration, I get a proper mystery at the heart of the adventure, and I get a narrative told with peerless style, through jump cuts and proper choreography, and on a realistic scale, for once, where every death can feel significant, and there's no ludo-narratological dissonance (yeah, I borrowed that phrase from the guy who wrote Far Cry 3, and he didn't like it either) as the bodies pile up and the arthritis takes hold in-between the chirpy and gymnastic cut-scene capers.

There are even a couple of neat jokes at my own expense, as I'm constantly encouraged to pick up guns and ammo I'll never get to use, and ceaselessly prepared for a shoot-out that I won't be invited to. Isn't this an interesting approach, actually? No violence, just aftermath. No action, just the tension that precedes it. Hitchcock once explained the difference between surprise and its more refined, more satisfying cousin suspense by saying that the former is when a bomb hidden underneath a table suddenly explodes, and the latter is when two people are sitting at a table and you alone know there's a bomb underneath it. Brendon Chung is a rather Hitchcockian designer, I think.

Why not just do it as a film then? Why not just watch the game on YouTube? Because in some powerful yet mysterious way, a certain element of control makes Thirty Flights all the richer, whether you're just lingering in the corridor of a bar to read the framed newspaper headlines on the wall (All hail the Mecha Presidente, I guess!), leaping behind the bar itself to read the drinks labels and spy the concealed handgun, or even stepping off a gangplank into the clear pool of a secret grotto, to see the barrels that keep the walkway afloat.

Slow down - try to steady the game's mad pulse for a second - and you get a sense of how deep the fiction might go, how far the world extends outside of the narrative and the narrative frame, around the bends of the game's blind corners and behind the jangling hinges of its locked doors. Abel's so wilful, so competent, so decisive, that this is my only way of bringing my own doubting, fretting nature to bear. I lean on a wall and count the security camera balloons as they bustle past. I spend quality time with a peculiar, imperious, inscrutable cat who occasionally flashes orange.

Is this why I love Thirty Flights of Loving? Not really. It's why I happen to love it today, and part of the reason why a game that technically runs for fifteen minutes or so has actually lasted me three or four months as I continue to turn it over in my head. Tomorrow may offer another reason, I guess, and another kind of love. That's video games for you. Beyond that, next year will hopefully bring a brand new Brendon Chung offering: it's called Quadrilateral Cowboy, and the current demo build starts with a lone biker approaching a speeding train while Clair de Lune plays over the soundtrack. Who's the biker? What's on the train? Why's Debussy gotten himself involved?

No idea, but I can't wait to find out - and what better way to end a year is there than that?