Gameboy wonder - the miniature epics of Daniel Linssen

Meet the Australian indie whose game jam creations are keeping the 8-bit generation alive.

Even today, in the age of 4K screens wider than living room walls and (theoretically) mainstream VR headsets, Nintendo's Gameboy exerts a peculiar fascination. The hardware itself may have long since ceased production, but it continues to bewitch developers - take a tour of the indie storefront Itch.io and you'll soon be up to your nose in tributes, from first-person horror games coated in LCD fuzz to borderline copyright-unfriendly riffs on The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening. How to explain this enduring appeal, the draw of nostalgia and Nintendo's peerless first-party licenses aside? For Daniel Linssen, an independent based in Sydney whose games are among the wittiest and most elegant I've played, it's a question of limitation.

"When you're working with only four colours and tiny sprites, it seems possible to find the perfect sprite for a particular object," he says. "There are only so many possible combinations, after all. And as the number of possibilities increases I find myself agonising over details that become less and less significant. So even though a higher resolution or more colours would make the game look 'nicer', there's a certain satisfaction to finding the best solution in a very limited space, rather than a good solution in a much more open space."

The idea of doing the most you can with a little is integral to game jams, which invite developers to cook up fully playable projects in days based on a (typically eccentric) theme. Much of the indie community's most pioneering work can be found among the submissions to competitions like the 14-year-old Ludum Dare event, and Linssen's own contributions - which draw heavily on classic 8- or 16-bit platformers and RPGs - are captivating efforts indeed.

The pick of the lot is Roguelight, an engaging study in light and shadow that was created for a Gameboy-themed Ludum Dare in 2014, which casts you as an archer descending through a procedurally generated dungeon. The twist is that your means of combat, flaming arrows, are also your means of navigation: every shaft you send through the neck of a trudging spectre or winged skeleton is an arrow you won't use to light a lantern, permanently illuminating the surrounding terrain.

Held together by ability upgrades that carry over between playthroughs, Roguelight is both a moody adventure and a work of pleasing delicacy and tightly-packed ramifications. It's one of those games where you discover a little more each time, the spartan mechanics notwithstanding: the terrain generator is a great balance of devious and predictable, and coins dropped by enemies sometimes bounce from view, a dangerous temptation to overreach yourself. Leaping into the black at some point is inevitable, in any case - the game's levels are separated not by chapter breaks but yawning chasms, easily stumbled into as you scour their furthest reaches for health refills.

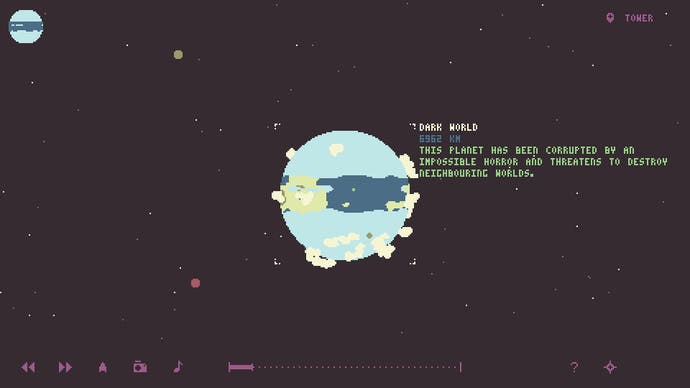

Diverse though they are, Linssen's projects share a few preoccupations - an interest in bending beloved conventions out of shape, doing a lot with a single mechanic or theme, and a certain toy-like quality, the restful conviction that it's enough to tinker around with a virtual object, savouring its quirks and flourishes, rather than seeking to "master" it. Consider Planetarium, a beautiful pocket planet generator where you can alter the temperature of a world in hopes of spawning a civilisation, launching rockets into space for the fun of it.

"Someone could pick a series of metrics - fun, interactivity, challenge, purpose, and so on - and decide that only works above certain thresholds counted as games, but doing this feels fairly arbitrary to me," he remarks. "I'll happily say that Twitter Island and Planetarium are lower on most of these metrics than something like Roguelight (and so might not be considered games to some people), but I don't think this makes them any better or worse."

?What really draws me to Linssen's oeuvre, though, is his interest in the opportunities and vagaries of framing devices. Much ink is spilt on the finer qualities of video game environments, but just as important are the structures through which we investigate those worlds, the directorial strategies and interfaces that shape, colour and pace our consumption of virtual terrain. This commonly happens without our knowledge - as gamers we are conditioned to see through HUD elements, disregarding the impact they may have on your sense of time and place - which is why making a point of the frame can be such an arresting technique. "For entirely sensible reasons most games use the entire window to display the world," Linssen notes. "But there are so many interesting possibilities as soon as you incorporate the player's view into the gameplay, and games that do this - Closure, The Unfinished Swan - often stand so far apart from the crowd."

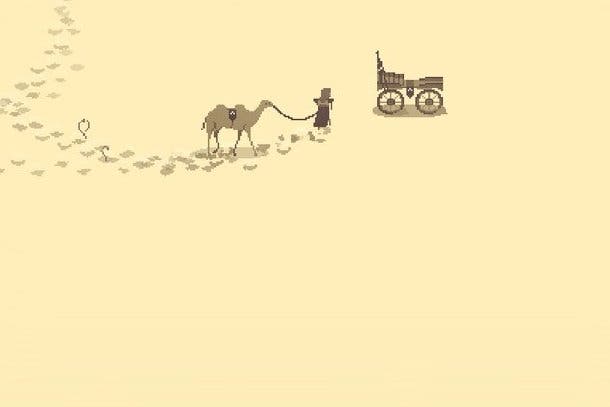

Another example of such incorporation is Linssen's Sandstorm, a Journey-esque trudge across windblown dunes in which the camera wallows to and fro as though mounted on the bow of a ship at sea. To survive the wasteland, you must learn to compensate for this waywardness, using landmarks such as the occasional streaming pennant to orient yourself in the gale, while keeping the other eye on the trail of footprints at your back.

Reap also plays games with visibility, albeit to less confusing effect. A minimalist Robinson Crusoe adventure in which you sow turnip crops and hack down trees to build rafts while scouring islands for treasure, the game represents day and night as an expanding and contracting field of view, its rim travelled by a jovial storybook sun. In birdsong, meanwhile, the display has a severe case of fisheye - it actually shows the entirety of the playable environment as a compressed, gritty nimbus of platforms around the edges of the screen. When you jump for the edge of the FOV, objects swell abruptly to full size, threatening to throw you off tempo.

Some of Linssen's games give you direct control over their own borders. In windowframe, the winner of Ludum Dare 35, throwable stakes are used both to dust vampires and peg the FOV (which otherwise centres on the player's character) to the backdrop, allowing you to wall-kick from window edges and drag them around with the mouse to reveal or hide routes and projectiles. Outline transforms movement into erasure - your avatar scuffs away the level to reveal the previous one as you explore, a serious inconvenience when you need to back-track to a door and must remember where all the rubbed-out platforms were. It's the mirror image of Haemo, in which you spray your own blood with Tarantino-esque abandon to expose a featureless white layout, the idea naturally being to have enough juice left in your character's body that you can actually reach the exit.

Linssen has completed around 30 games in the course of his career, having dabbled with RPG Maker, Flash and GameMaker before a friend invited him to handle the art and movement for a Ludum Dare entry. Most of his creations are available for free or under a pay-what-you-want model ("I'd much rather someone play my game for free than never play it at all"). Game jams continue to be a vital source of inspiration and motivation. "Given the enormous growth Ludum Dare has seen since its inception I would have expected it to lose a lot of its personality and friendliness, but the community remains really supportive and considerate," Linssen notes.

Does he have a larger work in store? Seemingly not. Linssen's games are very of their moment - fleeting and unpretentious demonstrations of a tool or variable's potency, of what an active imagination can do when subject to an exotic restraint. And taken together, they are as thrilling an artistic journey as any million-dollar magnum opus you'll encounter. "I have an enormous amount of respect for people who can dedicate years to make a career-defining masterpiece, but I'm much too impatient to try that," he confesses. "I'd rather shallowly explore a dozen ideas then deeply explore just one."