Forget Go - Pok¨Śmon Snap is the series' greatest spin-off

And this week's Virtual Console release is the perfect opportunity to revisit it.

Most of us fancy ourselves as virtual photographers these days. Not everyone is an Ansel Adams, but the tools for taking pictures have never been more accessible, nor as readily available to so many. In most games, it's merely a matter of pressing a button: Share, or F12, or F10 if you're using Fraps. Or saying "Xbox, take a- ah, damn, it moved. Xbo- hang on. Stop listening. Xbox, take a screenshot". (Okay, it's easier for some than for others.)

Other games let you freeze the action and view it from any angle, zooming in or out, adjusting saturation, focus and bokeh - whatever that means - to get the ideal snap. It's fun to spend time framing and developing a beautiful shot, but it's not really much of a challenge. A good time, then, to rediscover the rarefied pleasures of a video game that requires care, commitment and sharp reflexes to properly master the process.

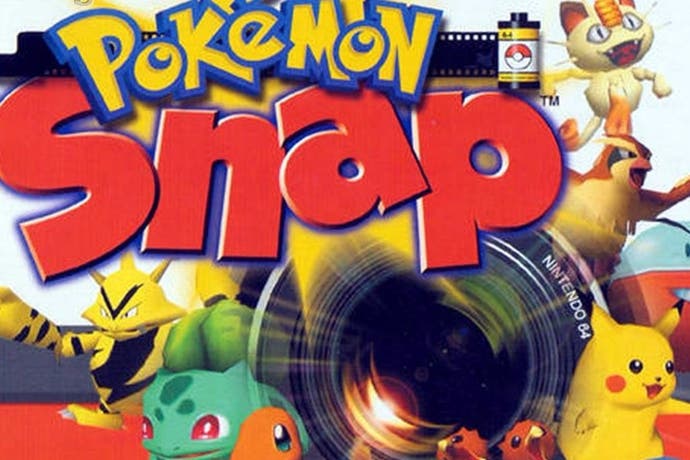

Pokémon Snap's arrival on the Virtual Console this week has nothing to do with this and everything to do with the current voracious appetite for all things pocket-sized and monster-shaped. On its release in 1999, this spin-off already felt like something of an oddity - partly because this wasn't exactly what people wanted from a 3D home console Pokémon game - but these days, it feels particularly quaint. That's not a complaint, either. Snap is as strange and fascinating as it ever was, mostly because there's not really been anything quite like it since.

That's less surprising when you consider that it melds two seemingly incompatible genres. Pokémon Snap is part rail shooter, part puzzle game. You move through stages automatically, riding on a bizarre looking vehicle along a fixed path that passes through diverse environments inhabited exclusively by Pokémon. Most are within plain sight, but some have to be coaxed out of hiding, and others require you to fulfil certain conditions before they'll reveal themselves.

Initially, all you have to worry about is pointing and shooting, and on your first few attempts that's challenging enough. It's deliberately a little awkward: normally you view the world through the photographer's eyes, and it's only when you squeeze the left shoulder button that you see everything through the viewfinder, which draws everything in tighter, confining your perspective to a square in the middle of the screen. In other words, you have to be sure you're ready to commit to a shot. It's an approach that was subsequently echoed in the Project Zero series, of all things, the unwieldy Camera Obscura providing comparable means to a different end. There's a similar tension at play in both games, however, because timing is so crucial. Taking pictures might be enough for some monsters, but success demands you take good ones. And that, much like the real thing, is something of a fine art.

Pokémon Snap doesn't have the usual hooks of a rail shooter to keep you coming back. There's no peril, so you don't repeat levels because you died before the end. There are no combos or score chains. You'll need to figure out the unlock conditions for certain stages, but the real replay value here stems from your own keenness to improve your tally on individual shots. The in-game photo album is a key factor, serving as a permanent, tangible reminder that there's always room for improvement.

One of Pokémon Snap's best tricks is that it doesn't automatically select your best shots; rather, it forces you to consider them all at the end of each trip before you present them to Professor Oak for judging. When you've got a few decent ones, you'll agonise between them: a good close-up shot might earn extra points for size, but by the same token you might lose some if the picture cuts off the Pokémon's tail. He's not easily impressed, either. Yes, you reacted quick enough to capture that fast-moving Zubat, but it wasn't in the middle of the frame: "You were close!" he says, in that peculiar, high-pitched yelp of his. Many a player will have cursed him (you might have a creature within the frame in its entirety, but if it's not dead centre, you're not getting that 2x bonus) but his grading is always pretty consistent. His exacting standards are merely further encouragement to stick at it.

It's a game that rewards an inquisitive eye and a willingness to experiment. You might catch sight of a collection of glowing lights inside a narrow cave opening - snap it, and when you study the developed film an ethereal outline of Mewtwo appears. There's plenty of interplay between the Pokémon, leading to moments of genuine surprise and delight - throw a pester ball into the water, and a Magikarp will splash out onto the shore, only to be thumped over a mountain by a nearby Mankey, giving you the chance to evolve it into Gyarados later in the level. And if you want to punish Mankey for such an outrageous show of violence, you can send a Squirtle shell to topple him from his perch - which in turn sees him reappear in front of a switch that triggers an alternate exit.

Such happenings are a sign of the playfulness that producers Satoru Iwata and Shigeru Miyamoto brought to Snap. But they're also, in an abstract way, analogous to the kind of creative approach that makes for the best real-world nature photography. It's a surprisingly educational game, in fact, not only promoting the kind of discipline and patience needed to become a good photographer, but also teaching you to trust your instincts, and that curiosity is often rewarded. I speak here from personal experience: my son has spent dozens of hours on the Wii Virtual Console edition, and his save file has a complete album, including an elusive 10,000 point Mew shot. A love of David Attenborough's work has undoubtedly played its part, but Pokémon Snap is also a big reason why he's already decided to become a wildlife photographer when he grows up.

As such, we've both bemoaned the absence of a sequel, for which 3DS and Wii U always seemed tailor made. (I even had an idea for a co-op mode on Wii U: one player could be a spotter, using the TV display to guide the GamePad photographer towards points of interest.) Sure, Pokémon Go might be letting millions of players hunt Pokémon within real world environments, from Pidgeottos in parks to Jynxes at junk food joints. But while catching 'em all is good, healthy fun, I know we're not alone in wishing for another opportunity to snap 'em all instead.