Entering the Avatar Machine, VR's next big step

Free your mind.

If you've played games, you're undoubtedly used to controlling an avatar in a virtual world. No matter how immersed you become in a game world on the television screen, though, your mind stays firmly on the sofa, fully aware that your hands are holding a controller. Yet it turns out to be surprisingly easy to fool your brain into thinking it's somewhere else entirely. Two people from completely different backgrounds have both discovered that 'freeing your mind' simply requires a few leads and a camera - and that merging video games with real life can have profound effects.

Marc Owens' background is in craft. His initial training was in manipulating metals, ceramics and plastics, but in 2006 he began an MA at the Royal College of Art in design products, a course that focused on how to approach functional items from unique perspectives. It was at this point that he became interested in objects that bridge the physical and virtual worlds, and for his 2008 project he hit on an idea that stood out as radical even among the cutting-edge work of his RCA colleagues.

Marc had always been a keen gamer, and he had a particular fondness for third-person games such as Grand Theft Auto and Max Payne. He'd also become interested in networked games like World of Warcraft and Second Life, and was especially fascinated by the way that people behaved in these worlds compared to how they behaved in real life. The phenomenon of 'griefers' as they were then often known (nowadays more commonly called 'trolls') interested him: what allowed people to behave in such an aggressive and disruptive way?

AVATAR MACHINE - MoMA from MARC OWENS on Vimeo.

It was at this point that he started wondering about how to recreate the game world in real life; what eventually became known as the 'Avatar Machine' initially started life as a critique of anti-social behaviour in games. The aim was to recreate the aesthetics and third-person perspective of games in a wearable costume to see whether users would replicate their virtual behaviour in the real world.

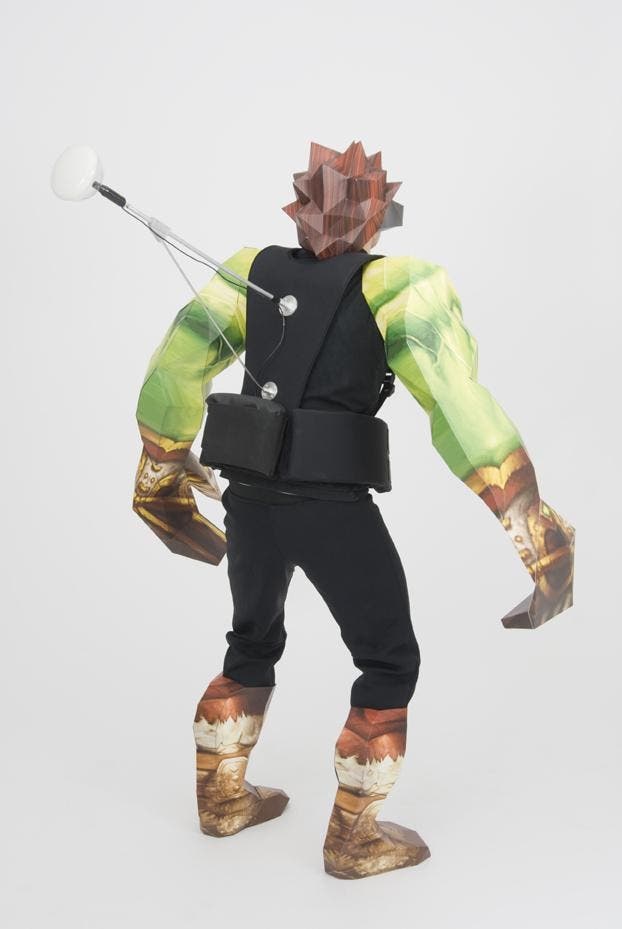

The machine started as a basic, unwieldy harness with a one metre pole sticking out behind. On the end of the pole was a camera linked to a head-mounted display, so the user could enjoy the odd sensation of staring at the back of their own head. Yet this initial prototype was disappointing. Marc wanted a 'head to toe' view, just like in a video game, but this was impossible with the narrow field of a regular camera, which could only show the subject's head and shoulders. To solve the problem, Marc came up with an ingenious solution - he pointed the camera away from the subject at a convex mirror, meaning the wearer could see the whole of their body. This was what Marc calls his "eureka moment".

The next step was to design the costume. Marc wanted to recreate the exaggerated build of characters in World of Warcraft, with big shoulders and hands, as well as sharp polygonal edges to indicate that the costume didn't quite belong in the real world. The finished version even gave the wearer manga-style spiky hair, and later Marc created a sword for that authentic video game feel.

Eventually it was time to try out the Avatar Machine on the public. Marc exhibited the machine as part of the designers in residence programme at the London Design Museum in 2009, and he watched with interest as attendees clipped themselves into the costume. At first he found that they would move very slowly and tentatively, as if they were exploring a body that wasn't their own. He describes it as almost like a 'rebirth' - the revelation of controlling a body from a distance that looked nothing like your own. He noticed that the wearers began testing the limits of their new body: one man set himself the challenge of trying to climb some stairs, and succeeded - just. Gender stereotypes were very much in evidence, as most of the girls attempted to hug each other, whereas most of the boys tried fighting. It was a fascinating social experiment, but soon the Avatar Machine was packed away and sent further afield for exhibitions. It has since been exhibited in Norway, at London's Victoria and Albert Museum and the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

But the story of the Avatar Machine doesn't end there.

Unbeknownst to Marc, hundreds of miles away in Switzerland, Professor Olaf Blanke was creating an Avatar Machine of his own. As founding director of the Centre for Neuroprosthetics in Lausanne, Olaf has dedicated his career to investigating body perception and its relevance to self-consciousness: in other words, where we perceive our 'self' to be.

Based on earlier research on neurological patients, he began a study in 2010 that, by sheer coincidence used almost the exact set up of the Avatar Machine, with a lightweight harness and a camera mounted on a 1-metre pole, connected to a head-mounted display. Both he and Marc independently came up with the solution of a backwards-facing camera pointed at a concave mirror in order to allow the subject to view their whole body. However, Olaf admits his version of the machine "didn't look as cool" as Marc's.

The idea for the experiment emerged from a real-life neurological phenomenon whereby people experience meeting their own double. "Some people experience visions of seeing an exact double in front of them at a distance of about two metres, often facing them," says Olaf. "When they raise their arm, the double does too." Other people see or feel their shadowy duplicates walking alongside them. Olaf aimed to recreate this uncanny experience in the laboratory in an attempt to learn more about the neurological process behind it.

He found that when people put on the head-mounted display and saw themselves from another perspective, they began to lose awareness of their own body. It was as if people wearing the avatar machine transferred their mind into the camera and perceived their body as if it really was in front of them - a true out-of-body experience.

Olaf aimed to quantify how 'real' the illusion was, and his data showed that the machine had an astonishing effect on perceptual and physiological functions. Bizarrely, he found that users' bodies cooled down when they perceived that their minds were somewhere other than their own body. He also found that they were less aware of pain: when a mildly painful stimulus was pressed against the users' skin they were able to tolerate higher levels of discomfort than when they weren't wearing the apparatus.

Olaf went on to develop his research further, this time linking up the head-mounted display to an avatar in a virtual environment, like a video game, in which users saw their virtual selves from a third-person perspective. This seemed like the natural next step: "Virtual reality is more freeing," says Olaf, "the only limitation is the programmer."

He developed a suit that would replicate the users' movements on the screen, as well as monitoring their brain functions. To cement the illusion, he would touch the subjects at the same time as their avatar was touched by a virtual object in the simulation. He found that users transferred body ownership to their avatar: if a threat was presented to their avatar in the virtual world, their real-life bodies showed a classic biological response to threat: that is, the skin conductance response, whereby the skin momentarily becomes a better conductor of electricity.

Fascinatingly, Olaf found that users were also able to 'adopt' a body that wasn't their own. Even if presented with a virtual avatar of a different size or gender, the subjects' minds were just as willing to transfer ownership to the virtual body as when presented with an avatar that resembled their real body. The same even held true if the subject was an adult and the avatar was a child. Interestingly, Olaf found that users even started behaving more like the virtual versions of themselves.

Olaf explains that our brains are so tied in to perceiving the world through vision that it is relatively easy to 'trick' the mind into thinking that it is somewhere else; other stimuli, such as touch, serves to reinforce the illusion. But no matter how intense the experience is, our brains flick back to 'normal' as soon as the head-mounted display is removed, with no lasting effects.

Olaf thinks that the technology could have uses in medicine. Because the avatar machine numbs painful stimuli, it could be used for the treatment of chronic pain. It could also have applications in the rehabilitation of stroke victims or in the treatment of epilepsy. Sufferers of 'phantom limb' pain, whereby people with an amputated limb continue to feel pain as if the limb was still there, could also find their symptoms reduced in their virtual avatar, and Olaf is eager to put this hypothesis to the test.

He was intrigued to discover that Marc had created an almost identical set up to his own work through the background of video games rather than neuroscience, and he's quick to see the potential applications of the system in video gaming. "The dream is to be part of the game, and we have the technology to make that happen."

Marc also sees an exciting future for this kind of technology. He reckons that alternative reality (AR) will become mainstream sooner than we think through systems such as Google Glass. Both he and Olaf agree that we'll see increasing incidences whereby AR is used to make the real world into a game. Marc thinks that marketing teams will get there first: "Whereas we used to think that you could only power up in a game, soon you'll be able to 'power up' by eating a Subway sandwich."

And with costs tumbling all the time, the future may be here sooner than you think: Marc recalls that when he built his first Avatar Machine the head-mounted display cost over £1000, but now much better technology, such as Oculus Rift, can be bought for a few hundred pounds. Does this mean we'll see a reboot of the Avatar Machine in the near future? "Maybe," Marc responds cagily, "That's all I can say for now..."

Meanwhile, Olaf is even more ebullient about directions that this technology could take us in. "If you think about it, the idea of having just one body is a bit old fashioned. We should have the brain power: after all, we have two arms and two legs, and we can control them just fine. Why not have two bodies, or four, or even six?"