Project xCloud tested: has Microsoft really delivered a portable Xbox One?

Can smartphone streaming come close to the local experience?

The smartphone is a unique device. Billions of them are in active use around the world, all of them are capable of internet access and all are equipped with video decoding capabilities - everything needed for streaming gameplay online. While it'll take time to completely solve the many challenges the technology has, the reality is that the smartphone can take cutting-edge games to people and places that consoles can't reach. That's the endgame with Microsoft's Project xCloud - to add a new way to play for the console gamers of today but with an eye towards explosive growth in new markets, delivering Xbox games on a global scale without the need for users to buy Microsoft hardware. Everyone owns a smartphone, right?

As evidenced by the recent launch of Google Stadia, cracking the technical challenges in streaming gameplay isn't easy - and it's the key reason why Project xCloud is still in beta. Delivering movies and TV shows to a mobile device is a walk in the park by comparison: video can be buffered to cover up inconsistencies in data delivery, while the pre-recorded nature of video means that compression can be incredibly efficient. Any given frame can borrow data from prior frames or ones that have still yet to be displayed. Streaming gameplay video - interactive gameplay video - is a couple of orders of magnitude more complex.

Google's Stadia aims to be all things to all gamers - a streaming service that scales from your phone all the way up to your 4K HDR TV - but xCloud as it presents right now is something quite different. It's significantly less ambitious in some respects, but delivers a far richer experience in others. Suffice to say that the key difference right now is that Microsoft's focus is 100 per cent on mobile devices - specifically the smartphone. It's highly likely that PC and TV options will follow in due course, but the emphasis of the xCloud beta is all about getting the experience right on everyone's favourite companion device.

There are four key components to the xCloud experience: the server blades, the client devices, the controller and the app. The servers are currently third generation iterations, running on custom motherboards but still based on standard Xbox One S silicon. Microsoft has achieved a 30 per cent drop in power consumption by using the Hovis Method - the technique of individually tuning power delivery for the needs of each individual processor, a system first used with Xbox One X. The server blades run customised low-level software that runs the OS as per normal, just like a normal Xbox One S, but also interfaces with an external video encoder on the motherboard, tuning the feed to best suit the connection to the user.

Based on my discussions with Microsoft at the recent X019, there are a couple of interesting facts here: first of all, the Xbox One S silicon is set to output at 120Hz, lowering latency by ensuring that new frames reach the encoder as soon as possible (the onboard encoder in the Xbox One S processor used for game capture isn't active for xCloud service). Secondly, the CPU component of the processor runs at a higher clock than standard retail units, in order to accommodate the extra demands put on the chip by the encoding pipeline.

The client device is the next key component and from our testing, the choice of smartphone can make a significant difference to the experience in terms of latency. The cellular radio or WiFi controller can add lag and likewise with the Bluetooth radio that interfaces your phone with the joypad (Microsoft says that USB controllers will work according to driver support in the device, but I had no luck with this). And just like an HDTV, the smartphone screen can have its own display latency - something we can't measure.

Then there's the choice of controller. Right now, the preferred solution is to take a standard Xbox One pad (later S, X or series two Elite models are supported) and connect up via Bluetooth, using a clip to physically pair the two devices. It works, but it looks somewhat ungainly and I can't help but think that the ultimate solution here will be significantly more streamlined. For part of my testing, Razer supplied me with its Junglecat controller which essentially brings the physical form-factor of Nintendo's Joy-Cons to the smartphone world. A bespoke case is attached to a compatible phone (I used the Razer Phone 2) and then the Switch-like controllers slot into place. It solves the form factor and controller issue completely, but as much as I adore the handset itself, I'm not sure the Razer Phone 2 is the best phone for gameplay streaming - as we'll discover a little later on.

Finally, there's the app. Simply download from the Google Play store, input your Microsoft account details and you're good to go. A simple interface allows you to pick and choose the game you want to play, a check is carried out to ensure a compatible controller is attached and then there's a fairly lengthy pause as your game is cued up for streaming. Loading times (boot up and in-game) can be fairly prolonged, though loading is generally faster than a standard Xbox One S console - 52 seconds on an S to boot Halo 5, vs 36 on xCloud, as an example. The bottom line is that CPU speed is intrinsically linked to loading times (it's not just about pulling in data, it's also about decompressing it) so in this sense, while there is an improvement over a standard retail console via server-grade storage, the extent of the speed boost varies on a per title basis.

Once you're into the game, Project xCloud is a portable, handheld Xbox One. It acts exactly like an Xbox One because it is an Xbox One. Cloud saves sync up automatically, Achievements are earned and stored just like the local experience. Xbox Live functionality just works because you're still effectively gaming on an Xbox One console, it's just running remotely. What's more, because it's running on Microsoft Azure, the Xbox One blades are effectively peers with the cloud servers - I ran the matchmaking latency test in Gears 5 and noted a 15ms ping to Western Europe servers on my local console vs 1ms on xCloud. In fact, Microsoft tells me that this reduction is latency actually caused anti-cheat measures to kick in during early testing.

The platform holder could have run PC versions of the same games on x86 server hardware, but once you experience xCloud, you realise why setting up bespoke hardware in the datacentres makes sense: the entire library of Xbox One games works out of the box with the mobile cloud experience perfectly integrated into the wider ecosystem. And this is all before cloud-specific XDK features are integrated - the xCloud beta doesn't feature the touchscreen control overlays we saw in the initial reveal, for example, but they are still in development. Game makers will also have the ability to tailor their games specifically for xCloud - HUD elements appropriately resized for smaller screens being one example.

All of which brings us to the twin topics that dominate any Digital Foundry discussion of cloud gaming: image quality and latency. And it's here where we really need to stress that the current xCloud beta is exactly that - a work in progress designed to amass feedback in tuning the final product. And that's exactly why I haven't reported on the system up until now: xCloud didn't work properly on my home fibre connection, despite meeting all of the requirements and then some. It turns out my ISP - Sky - was dropping up to two per cent of packets when the network was congested. Microsoft was able to identify this via me submitting feedback through the app, which sends xCloud logs back to base (so if you are having problems, you can genuinely help to improve the service by doing this too).

The situation with my ISP has improved recently, but to be on the safe side, I opted to use the same 200mbps Virgin Media connection I used for Stadia testing, the point being that I want to review Microsoft's technology, not the quality of my specific connection. xCloud itself beams a 720p60 video stream to your phone and there is an eye towards economy in terms of bit-rate. This has an impact on image quality, depending on the content. It's at this point where we stress again that the beta isn't finished code, but more to the point, the video stream is designed for viewing on smaller screens. As we've seen with Nintendo Switch, having a relatively small display as the canvas for gameplay hides a lot of unwanted effects - and so it is with xCloud.

Image quality is best defined as fine overall when viewed on a phone, but it's very definitely a mixed bag depending on the content fed to the encoder. The first couple of levels of Halo 5 are mostly set in darker environments - easier to compress, so image quality holds up well enough, macroblocking only noticeable on the phone display during screen-filling pyrotechnics. On a smaller screen, you can tell it isn't pristine, especially when you move into brighter environments, but it holds up overall. In fact, you start to appreciate that the smaller screen does indeed deliver the 'Switch effect' in masking compromises to image quality beyond the encoder. Halo 5's poor texture filtering (solved on Xbox One X) barely registers here.

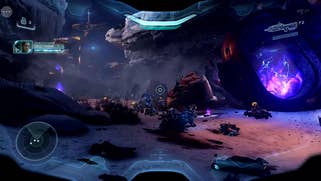

Halo 5 works well and the magic of a portable Xbox One is palpable. Compare and contrast with Killer Instinct. Bright colours, fast action and micro-level detail are a nightmare for any video encoder to deal with and even on the smartphone screen, compression artefacts are as clear as day. Using the game's replay system to produce identical captured content (via saved bouts playing back on both local and cloud systems) we really get a sense of how image quality buckles when presented with the most challenging of content in the thick of gameplay.

After that, sitting somewhere in the middle between Halo 5 and Killer Instinct is Gears 5, where the experience is mostly fine, though some content (fog, waterfalls) can cause compression artefacts to kick in to a degree that is noticeable on a smartphone display. Microsoft tells me that variable bit-rate encoding is already in place with xCloud, but I would hope to see user options added in to set a specific quality level. While bandwidth is likely to be limited outdoors, it would certainly be useful to have the option of ramping up the data rate when at home and running from WiFi.

Overall, the encoder works fine across a range of different games and the small size of a smartphone screen goes a long way in mitigating the inherent compromise in using compressed video. The comparison images on this page are very harsh in that sense as they expose the limitations of using video compression running on a tight bit-rate, and the imagery is blown up to a degree you will never experience on a smartphone screen. The macroblocking is generally less noticeable on the phone itself but while Killer Instinct may look like an outlier from the first examples shown here, it's not too difficult to find other titles that struggle, even when viewed on a phone. Forza Horizon 4 moves a lot of high detail artwork about at high speed and a lot of that fine detail is clearly lost.

Latency is our next port of call and it's here where there is a massive divide in opinion based on the reports I've seen online - and I think I know why. In assessing cloud systems, I like to remove as many variables as possible from lag testing. Testing with WiFi is a no-no owing to its variability, while display lag changes on literally every screen you test, sometimes to a dramatic degree. xCloud adds a further lag factor that may change from phone to phone: Bluetooth radio quality.

With xCloud you can remove WiFi from the equation by using a USB dongle and turning off all forms of wireless networking. However, I couldn't get USB wired controller functionality to work at all (though Microsoft assures me it will work on several handsets) meaning latency results could be affected. Meanwhile, I planned to use a USB-C hub with HDMI functionality to bypass the display lag issue but this seemed to add a degree of lag on its own to the point where I couldn't trust the results. I tested the Razer Phone 2, a Samsung Galaxy S9+ and a Redmagic 3S one after the other in an easily repeatable lag test - pressing the jab button in Killer Instinct's practise mode and filming it with a high-speed camera - and found anything between up to a 36ms difference in response between the phones.

Whether the variance is down to display lag or Bluetooth radio can't be ascertained but the fastest phone was the Redmagic 3S and surprisingly, the Razer Phone 2 was the slowest with the Galaxy S9+ somewhere in the middle. I actually tested the Razer Phone 2 at 60Hz, 90Hz and 120Hz display modes with very, very similar results, so I wonder if there is a weakness in Bluetooth performance. Hopefully Razer can look into the puzzling level of lag here, as the Junglecat peripheral is excellent, solving the big controller issues inherent to cloud gaming on a phone.

| Killer Instinct | Latency | Difference |

|---|---|---|

| Xbox One/CRT | 66.7ms | - |

| Xbox One/Samsung RU7100/Game Mode* | 77.4ms | +10.7ms |

| Xbox One/Samsung RU7100/Game Mode Off* | 142.9ms | +76.2ms |

| Xbox One/LG OLED E9/Game Mode* | 79.8ms | +13.1ms |

| Xbox One/LG OLED E9/Game Mode Off* | 117.1ms | +50.4ms |

| Project xCloud/Redmagic 3S | 121.1ms | +54.4ms |

| Project xCloud/Samsung Galaxy S9+ | 142ms | +75.3ms |

| Project xCloud/Razer Phone 2 | 156.7ms | +90ms |

* HDTV latency measurements by Rtings.

Xbox One S in local form was tested by hooking up the console to a Sony FW900 CRT monitor via an HDMI to VGA converter and this effectively represents the optimal local experience, completely factoring out display latency. It's the best case scenario for the core hardware and our starting point for understanding lag across all other tests. I then visited noted HDTV review site Rtings and grabbed input lag results for the Samsung RU7100 - which tops the charts for lowest input lag - and the LG OLED E9 (simply because if I were buying a screen now, it would still be an LG OLED). Rtings measurements with Game Mode on and off are added to Killer Instinct's base latency to give something closer to real-life gaming results, something that more closely matches the phone experience where display lag cannot be removed.

The results here are fascinating. Assuming the Rtings results are on the money (and their testing methodology is sound in my opinion), a Samsung Galaxy S9+ running xCloud produces a nigh-on identical result to a Samsung 2019 display running with game mode disabled with the Redmagic 3S running xCloud actually 20ms faster in response. The Redmagic 3S shows 54.4ms of extra lag up against the CRT experience, which is an excellent result bearing in mind that this includes both Bluetooth and display latency. This is a relatively cheap flagship-level phone produced by ZTE, with a 90Hz AMOLED screen. It's a fascinating piece of kit (active cooling!) that I'll be looking at more closely in future.

The spread of results in the table also demonstrates why platform holders like Microsoft, Google and Sony believe that cloud gaming will take off in future. Most gamers out there are likely hook up their consoles to their screens without engaging game mode - they may not know what it is or even why it's there. This suggests a degree of flexibility in how mainstream users perceive latency and how cloud gaming can compete with the local console experience, even if an Xbox One running on an HDTV with game mode enabled is significantly faster in response and likely always will be.

The xCloud beta is a promising hint of the full experience to come from Microsoft, and the 50-title line-up we have to test in the here and now demonstrates how Game Pass gains an extra dimension through its addition: the notion of having access to so many games in such a convenient way in a portable, take-anywhere form factor is simply brilliant. Game Pass's strength is the length and breadth of titles you can experience with xCloud removing the final element of friction - download times. Even just as a sampling mechanism before committing to a download on a local console, it's highly compelling.

If the service launched as is, I think there'd be many very happy users out there but at the same time, my testing has highlighted that as strong as the core technology is, Microsoft is not entirely in control of the 'end to end' experience as it is when delivering a console. Beyond network conditions, what surprised me was how variable the feeling of latency was from title to title and on phone to phone. The concept of latency and how it is 'felt' is a difficult topic to articulate, because the experience is so different from person to person, from device to device. There were times when playing Halo 5 didn't feel 'right' on the Razer Phone 2 with the Junglecat peripheral, while playing Shadow of the Tomb Raider did - despite objective latency measurements showing that Halo is always more responsive, likely owing to its super-low native input lag. I can't describe why that is, but I couldn't shake that feeling. Meanwhile, the Redmagic 3S is the fastest phone, but 60fps video playing back on a 90Hz screen can cause judder issues.

I do think there's very definitely a market for a new kind of Xbox then - a Switch-styled client device with input controls, networking and display tuned for ultra-low latency. The Razer Phone 2 with the Junglecat add-on demonstrates beautifully that there are enticing possibilities for a handheld Xbox that delivers a comprehensively improved ergonomic experience over the phone/clip combo but this does need to be combined with internal hardware designed to offer the best possible xCloud experience. I'd also be fascinating to see how xCloud runs on the Switch - rumours continue to do the rounds about discussions between Microsoft and Nintendo on this very topic.

Ultimately, I came away impressed with this early look at xCloud - mostly from the fact that at its best, it's essentially delivering a fully handheld Xbox experience. It's not the finished article by a long chalk and I still think there are fundamental problems with the concept - just as there are with Stadia. Bandwidth remains a limited commodity and gameplay over IP doesn't have the latitude to adjust to different demands on your connection from various users in the house in the way that YouTube or Netflix can. But the core technology works - and bearing in mind the scale of the challenge here, that's a remarkable result.