David Braben Discusses the Raspberry Pi

Pi and chips.

"We're getting our children through education by anaesthetising them, and I think we should be doing the exact opposite: we shouldn't be putting them asleep, we should be waking them up to what they have inside of themselves."

Sir Ken Robinson, in an abbreviated talk at the RSA on the need for radical reform to our education system, is talking specifically here about what he sees as the mislabelling of ADHD as an epidemic. Not, he stresses, that ADHD doesn't exist, but that children are being routinely medicated to survive a system that no longer recognises the historically unprecedented demands on their attention - a misplaced punishment for our own inability to adapt our education system, and therefore our children, to a world that's barely recognisable to even the last generation.

He argues that the square peg of a schooling system originally conceived to support the demands of the Industrial Revolution is today being hammered clumsily into, well, let's call it a black hole. One in which economic certainties about the future are non-existent - a frightening world where the guarantee of a job in exchange for playing the game, ticking standardisation boxes and working hard to gain a degree that secures a comfortable living no longer exists. More dangerously, as Sir Ken argues, today's children know this is a lie.

How then to nurture the technical creativity of children, while giving them the skills to survive in an uncertain future? The good news is that the UK government is listening and changing one critical area of education, and ICT will return to its more creative and scientific roots in the future - rather than remaining positioned as a platform for teaching software skills.

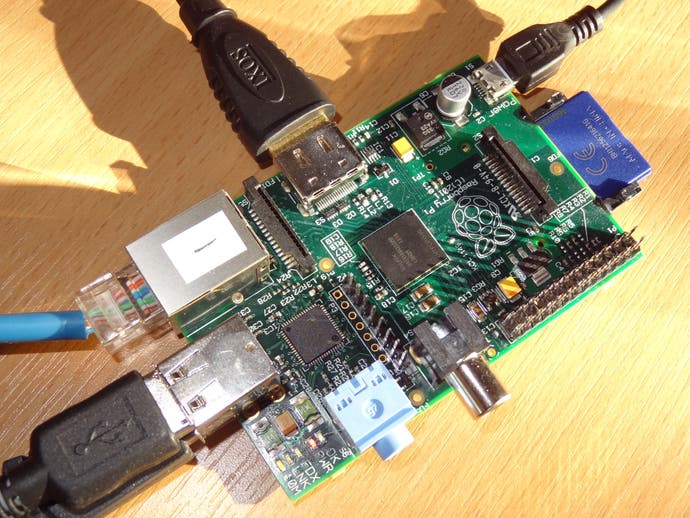

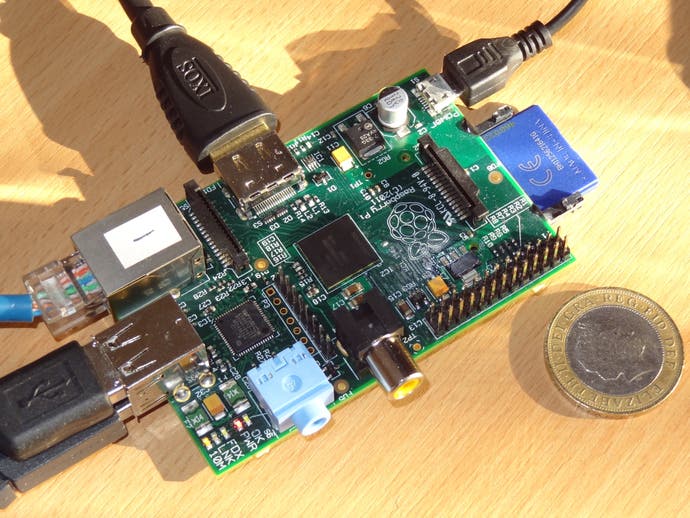

Independently of this, a different - yet fortuitously timely - revolution has been quietly brewing thanks to the efforts of ex-Cambridge University lecturer Eben Upton and the Raspberry Pi Foundation. Earlier this month we travelled to Cambridge to visit foundation trustee and head of Frontier Developments David Braben, and discuss the upcoming low-cost, credit card sized computer designed to return creativity and core skills to computing education.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"If you ask a kid, 'Oh, would you like to be an app designer?' - using the more modern parlance than a programmer - they say: 'Wow, could I do that?'" Braben says of the untapped enthusiasm of schoolchildren. "With a simple scripting language, you can. It breaks down a barrier, but it also creates a sort of secondary learning. Kids are motivated to create something, but they're accidentally learning as well. I think the more we can capture that energy, the better.

Interest in the Raspberry Pi has of course not been limited to the educational sector, and a cross-generational audience of tech-enthusiasts has followed development of the device with delight. Did the enthusiasm for the project from 'children of all ages' come as a surprise to Braben?

"I did expect it. There's the techie community, of whom I count myself a member, who love things like this; the novelty of a complete PC that costs less than a game, and that you can do fun stuff with. We don't know how many people there are like that - I suspect it's a significant amount - but it's not huge and that's really who the developer versions are for, because I think they will be fantastic allies as well for us.

"We know at least a thousand schools represented on Computing at School, which is an informal group who care about getting computing teaching in school. Fingers crossed, it looks like we've now actually achieved that. And so hopefully Raspberry Pi is something that will enable that to go to the next stage and make it more possible, and to be one of the teaching aids that they could use.

There's a danger in writing about the education system - that you'll be assumed to be firing a misaimed shot at (and doing down) the hard work of those teachers who would dearly love to have the tools and support to match their commitment to inspiring children in the subject.

It's an important distinction to make, and the roadblock to progress is not just down to government targets or a surface-deep curriculum - there's the issue of the existing hardware itself. As Braben explains, the Raspbery Pi as a state-less device solves a number of the practical problems currently associated with IT in schools.

"It's very like the early days of the BBC Micro in that you can just press a reset button and a few seconds later it's back to a known state, which in education particularly is absolutely invaluable. If you think of one PC from another, how much they differ - they have different user-names, different directory structures, and quite often you have slightly different versions of the OS installed.

"When we first started looking at Raspberry Pi, we actually thought of it as a software platform, but more and more it became much more logical to do it as a hardware platform. If you think of a classroom with 30 machines in, just deploying a piece of software to those machines requires someone to sit in front of them, pressing a whole load of keystrokes - and not necessarily doing the same thing to each one, because it might be slightly different.

"Whereas in the days of the BBC Micro, a teacher at the front could just do a few key presses and deploy it to all 30 because they were in a known state, or could very easily be put into a known state centrally. I think that's the sort of philosophy we're trying to do here, so essentially if something bad happens to the software and it crashes horribly, you reset it and you're back to the [original] state as if it was new out of the packet. But that loop doesn't take 20 minutes, it takes less than 10 seconds, which I think is absolutely fantastic."

Outside of the education system, there will of course be well-meaning parents who wish to invest in the Raspberry Pi and encourage their children to develop their computing skills. Or self-learning enthusiasts like myself who have more coding cobwebs blowing around upstairs than they'd care to admit to. How are they looking to assist with those critical first steps?

"One of my personal objectives is to see a TV series based around technology, and we've been talking to people about it already. BBC Micro Live helped the BBC Micro a lot. It was a television programme broadcast by the BBC more than thirty years ago, but it had a secondary effect where people could see there was some interesting things you could do with it - but it didn't really take it much further because at the time, the technology was interesting enough.

"If you start losing the device itself as the important thing, and start looking at what you can do with it, then I think we can bring familiarity and comfort with technology to a lot more people and change the cultural negativity we have towards technology. We're consumers of technology, we're not users of technology any more as a rule."

This philosophy of exploiting readily available information to empower opinion-forming is tied into the repository planned by the Foundation to allow users to collaborate with each other, as well as share creations and assist with self-learning.

"It can connect to a central resource that we'll put in place, which is a website venue with a wiki as part of it. Somewhere people can create software, upload it and then download things other people have created. One of the things that teachers have said is that at the moment there's no one-stop shop for going to and saying 'I want some teaching materials, I'm teaching Key Stage 3 and I'm doing this subject.'

"There are so many wonderful pieces of teaching software that have been created by public-spirited people. I think it's great to be able to provide a venue for those where they are accessible. Also that they've been written in a way that works well on a device like the Raspberry Pi, and that you'll be confident that it would just work."

The Foundation's aims and ambitions are not just aimed at assisting the development of children within the western education system - the board itself has undergone a number of revisions to ensure it can be as globally inclusive as possible.

"We got a lot of contact from charities operating in the third world, saying that a big problem we have is laptops - laptops don't live very long in places like Africa, not just because of the desirability for theft, but also that it's a very unfriendly environment because of dust and damp. You tend to put it in the back of a Land Rover - you can imagine it bouncing around, how long a typical laptop would last, whereas something like this would probably just go in your top pocket.

"There are TVs everywhere so that's not a problem - the problem is that they're old-style analogue TVs, so we've added wired ethernet, we've got analog TV output etc. In the UK most households do have an HDMI TV, but the problem with that is they're the ones that are in the living rooms and are in use. Quite often people have an older TV in the loft and it may well be that the kid can blag it to use with Raspberry Pi."

Towards the end of our visit we spoke about the potential for the technology to evolve and upgrade in the future - tricky territory given the aim to provide a universal device designed to tear down walls, rather than build them. It prompts a question around whether Raspberry Pi is the device itself, or the philosophy that drove the Foundation to create it in the first place.

"I don't even know which, it's a bit of both. Really it's the philosophy. But in a sense it's the device as well. The foundation is called the Raspberry Pi Foundation - in terms of the device itself, if it runs on a Raspberry Pi we want it to run on a Raspberry Pi version 1.1.

"The potential is always there for it, but I think the really important thing is that it retains compatibility. Never is a long time, so I think for the performance to increase, the amount of memory to increase...but what I want to fight for is to make sure the spec of what a Raspberry Pi is, is still preserved.

"But the intention is to create something that's uniform and great for education. What I'd like is for Moore's Law to be used on price rather than performance, which is of course possible. But that's not to say the performance won't creep up!"

Could the Raspberry Pi inspire the next David Braben or the next Peter Molyneux to break through into the games industry?

"I imagine it will. I hope it will change the way people see the technology. If you just look at what people like Apple and Microsoft have done to user interfaces in the last 10, 15, 20 years, you'll see how much better they've got.

"Hopefully, they'll look back on the Raspberry Pi with affection in the same way I look on the Acorn Atom and BBC Micro. I don't necessarily mean they'll be doing it [game development] on this, but it will be the thing that they go dewy-eyed about."

Special thanks to the Eurogamer readers who participated in our community Q&A with David Braben. Responses from the session are included in this article.