Cocoon is Eurogamer's game of 2023

What is a great game made of?

Cocoon. Of course it's our game of the year. Cocoon is ingenious, elegant, and thought-provoking. It's precise, expressive, and generous. It takes game design forward even as it seems to emerge from its deep history. But more than anything, Cocoon is playful. Its puzzles, its tricks, all yield to playfulness.

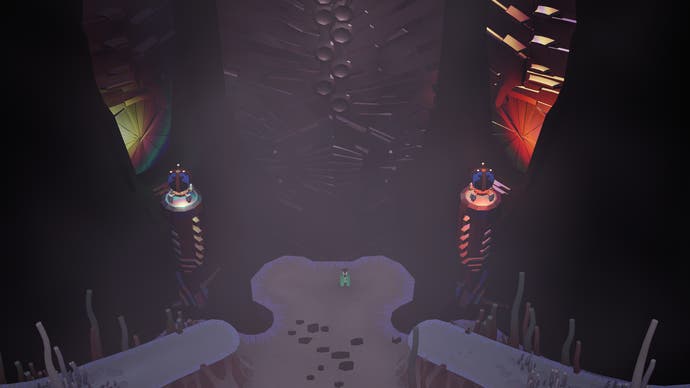

Hopefully you've played it yourself by now, but if you haven't, know this: Cocoon is a game about traversing strange landscapes, and discovering that these landscapes actually live inside a series of orbs. These orbs can in turn be picked up and carried around and taken with you as you explore other landscapes - landscapes which are themselves contained in their own orbs. You can be inside something that is inside something else that is inside the thing you are carrying. Cue much design brilliance.

Here is the thing, though. I've been playing Cocoon and thinking about it for a good chunk of this year. And more recently I've been talking to colleagues about it and reading through reader comments on it as part of our end-of-the-year articles. (Look for the reader list on December 31st: it's luminous.) And what's interesting to me, and almost disconcerting, is that there's this great, ingenious, singular game out there, and we all seem to agree on it.

We all agree that Cocoon is very clever - dazzlingly so. And yet we also agree that its true cleverness is expressed in the way that it makes the player feel clever. It goes to impossible places and manages to lead you there too. It quietly shuts off unpromising avenues of puzzle-solving thought, prodding you towards the correct solution without you noticing it. And yet you do notice it. I noticed it. We all noticed it - and we just loved Cocoon all the more.

So. There are at least two ways you can go with these Game of the Year pieces. One is the rehashing of the review - everything that's great about the game, but with a sense that these things have only deepened, become richer and greater over time. The other way is to poke a little bit, to try and see something else in the game. This is what I've been trying to do this morning, prior to writing this. And here's what I've got.

Cocoon is a clever puzzle game in a year that is pretty rich in clever puzzle games. But as I look at it now, I realise there's another more interesting trend it feels like it's a part of too. Over the last few years, I've half-noticed a bunch of games that seem increasingly interested in what games are made of. Not the mechanics or genres or traditions, or even the recurrent characters or themes or expensive licenses and expanded universes. I mean there are games that are interested in what games are made of. Rocks. Mud. Glass. Other things.

As an example, I think you could look at something like Birth. This is a game about loneliness in a big city, and it's beautiful and moving. But I love it because it's a game about pebbles and feathers and bits of rodent bone. It's about scraps of stuff, dried stuff, crumpled up, sharp-edged stuff. That's what makes it what it is.

Elsewhere, look at Sludge Life, and Sludge Life 2, which we got this year. A game series about urban ennui and isolation, sure, but also a game series about gloopy toxic waste, old bin liners, ash-tray dust and the sun-bleached shells of shipping containers. All of this seen through the scratchy, strobing, warping videotaped fish-eye of an old camcorder or somesuch. That's what Sludge Life is made of.

And look at what Cocoon is made of! Wow. Jeepers. You have puzzles and spatial-juggling ingenuity and a lot of challenges that are really about different kinds of doors. But you also have this wonderful, frightening mish-mash of substances. You have insect wings, fat tumours and adenoids and myelinated axons. You have hand-sculpted metal, and sandy rock, and swamp flowers and very fine circuitry. And this is all brought together so elegantly, so deftly, that you start to see new connections between the hidden world of technology innards and the microcosmos of insects: those grasshoppers with naturally occurring gears in their legs, that flea that Robert Hooke once sketched, paving the way for so much that is weird and reaching in modern art.

This, then, is the disciplined mind and the wild eye. And it's what I only notice when I also notice that I have an annoying tendency to look at games as collections of ideas, rather than what they increasingly also are: collections of things. This is Cocoon not in its influences (puzzles, doors) but in its material reality (tonsils).

Weirdly, I suspect a lot of this comes down to technology. You need to be able to render things in 3D pretty well to give them a convincing material reality. This thought alone makes me want to go back to N64 and PS1 games, back to when engines couldn't really do this, and marvel afresh at what these games now feel like they are made of in turn, having been born back when there was such a wide gap between what polygons could be made to do and what the world and its pieces feels like. (What is Mario 64 made of? I realise I have no idea!) Technology, yes. But you also have to look at the world, long and hard and close up, and yet with imagination.

Looked at through this lens I'm delighted to tie two big pieces of discovered joy from 2023 together. One is Cocoon, which really is as dazzling and transporting and generous as we all say it is, and the other is the art of Adriaen Coorte, which I found in Laura Cumming's latest book, Thunderclap: A memoir of art and life and sudden death, which I urge you to read.

In Thunderclap, in amidst works by Vermeer and Fabritius and other Dutch luminaries, I also found some asparagus, overlit and sharply realised with delicate, almost invisible brushwork, laid out on a stone ledge, but tilted away from us in such a heroic, alien pose they almost reminded me of a fleeing spacecraft from the opening of Star Wars. I will leave you to discover more of Coorte's strange, intensely beautiful still-life art yourself - it's worth doing. But like the makers of Cocoon so many hundreds of years later, here was someone who looked closely, intelligently, and creatively at what the world was made of, and what that stuff might be used for.

.png?width=291&height=164&fit=crop&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)