Artsy Porn & Sexy Larps

On games, bodies, and queer rights.

Hello! All this week, Eurogamer is marking Pride with a week of features celebrating the intersection of LGBTQ+ culture and gaming. Today, Sharang Biswas takes us on a tour of bodily pleasures, exploring the perhaps surprising connection between pornography and analogue gaming - and highlighting the creators designing in the spaces between intimacy and play.

At the 2020 San Francisco Porn Film Festival, I watched a pretty arresting piece named Tidal, part of a French film project called Vespéral.

At seven minutes long, Tidal focuses on a nude brunette woman and the half-a-dozen pairs of hands that touch her, stroke her, caress her, and appear to bring her immense pleasure. The scene is scored with a thrumming, meditative track. Clips of waves hitting the beach, whose to-and-fro movement is often mimicked by the motion of the hands, intercut our vision of the woman - not interrupting but punctuating. It was an exquisitely poetic, and highly erotic film. Even I — once described by a classmate at grad school as "gay as fuck" — was titillated.

Tidal comments on both the medium of film and the genre of pornography. The film invites us to look at the rhythms of a body and compare it to nature, to gaze unabashedly at a body feeling pleasure for pleasure's sake, with no overarching narrative, themes, or goals. And of course, if we touch ourselves in the ways depicted on screen while watching... well, it is a porn film.

Pornography is arguably the most "body-centric" genre of cinema, the literal depiction of naked bodies the least of the reasons why. The tingles, the swelling, the wetness that one might feel when engaging fully with a porn film constitute the goal of a porn flick, not just byproducts of other cinematic elements. The porn film expects, anticipates, and — dare I say — stimulates physical self-pleasure. Porn invades your body, breaking the fourth wall in ways that would turn Deadpool's costume green with envy.

Compare movies that are merely sexy to those that are created as porn. The aggressive, wrestle-tastic fornication in Brokeback Mountain and God's Own Country is certainly hot, but few would watch either of those movies with their hand down their pants. Equally, few would watch Gay of Thrones (not the Jonathan Van Ness one — the other one) or Twinklight for the plot or deep character development (trust me, I've tried with Twinklight).

Few other art forms engage the body like this. Sculpture, painting, installations, and even dance might make you aware of your body and its relationship to space, but these provocations tend to lie secondary to the audio-visual impact of the artwork.

Then, there's the world of games.

If the realm of bodily immersion cedes some of its territory to the genre of pornography, the rest must lie firmly under the authority of analogue games. Boardgames, card games, playground games, tabletop roleplaying games, and larps — these forms engage the physicality of participants in ways no other art forms can. Game designer and professor Ian Bellomy argues that, much like a PC, a PlayStation, an Xbox, or a Switch, the human body can itself be considered a game platform, with its own affordances and constraints. He compellingly illustrates features that make the process of playing a game on a "human platform" unique.

His most interesting arguments concern "experiential side effects". To Bellomy, the experience of playing a physical game rises above the mere inputs and outputs of the game system: "The children's game Snakes and Ladders and the folk card game War are experientially distinct, despite the fact that formal descriptions of both games involve the same amount of player input, namely: none at all. Similarly, drawing a random card from a stack of six is experientially distinct from rolling a die even though each method of randomisation is statistically equivalent."

Take Alex Roberts' award-winning tabletop roleplaying game Star Crossed. In it, two players portray characters who really, really want to get together romantically (and likely sexually) but can't for some reason invented by the players. Maybe they're rival kings. Maybe one of them is a bird and the other a mermaid. Maybe they're nuns at a convent. Whatever the explanation, interpersonal tension mounts.

What makes the game ingenious is that this tension is physically represented by a tower of Jenga blocks. As the characters interact, more and more blocks are removed from the tower. If the tower topples before the characters have a chance to confess their feelings, the pair's chance of coupling comes crashing down with the blocks. A game of Star Crossed, thus, is knitted with tension ("Tension" in fact, was the original title of the game). Each time your character acts, you must remove a block. Consequently, each move your character makes is laden with meaning, possibility, and stress. This stress resides, in a very literal sense, in your body: after all, it's your hands pulling the blocks, your clumsy fingers that might bring ruin to these desperately in love (or horny) characters. Star Crossed's emotional momentum is intimately tied to the physicality of the players.

Pornography and roleplaying, in some ways, are bound by similar logics. Both situate stories in bodies. Even if I refrain from active self-pleasuring, the erotic delight I derive from a spicy movie (not Twinklight) is only possible because I have some sense of what it feels like in my body. I can root the feelings and desires in my own skin.

Roleplaying games, for all their fantastical premises and arithmetic-loving rulesets, are only fun because we have a bodily experience of the world. Rolling dice and comparing disembodied statistics is rarely fun — imagining the crunch of bone as my mace connects with that of a shambling skeleton is infinitely more so, because I know what bone feels like, and can conjure up what the scene might be like. It's perhaps for this reason that modern roleplayers are so keen to establish table boundaries and calibration or "safety" tools while playing: there's a chance players can connect with real, bodily experiences that are not so pleasant.

The link between analogue games and the erotic is hardly a new discovery, though. Think of hormone-fuelled games of Spin the Bottle, Truth or Dare, or Seven Minutes in Heaven. Think of novelty dice or card games that have you randomise sexual acts with your partner. In fact, as scholars Tanja Sihvonen and Tuomas Harviainen note, "Larps and kink practices are easy bedfellows, as both are embodied and delimited activities involving an imbalance of power and guided by pre-set rules." The authors proceed to point out the many similarities and links between BDSM and roleplaying, especially larp.

Indeed, I recently experienced something along the lines of these intersections firsthand. At the 2023 Cleveland Leather Annual Weekend (CLAW), a prominent kink and fetish festival in the United States, I had the opportunity to participate in a lovely game of "Kinky D&D", where players chose erotic "punishments" for themselves as consequences for low dice rolls or narrative mishaps. It's quite something to receive an under-the-table blowjob from the barbarian while the rest of the party is fending off an armoured demon.

To contemporary queer politics today, art that forces us to examine our relationship to our bodies is vital. After all, queerness can be defined as a challenge to normative ideas about bodies: what gender a body "belongs" to, which types of bodies are allowed to have sex and how, these questions are at the heart of much of current political debate. Regulations pertaining to transgender athletes, laws prescribing how we can use bathrooms, the curtailing of reproductive rights, and anti-sodomy laws — these issues are all tied to the stories we tell about our bodies. "This is a masculine body" is not very different from "This is an orc body": both are stories we tell, both can be performed.

As Judith Butler famously wrote, "Gender is instituted through the stylisation of the body and, hence, must be understood as the mundane way in which bodily gestures, movements, and enactments of various kinds constitute the illusion of an abiding gender".

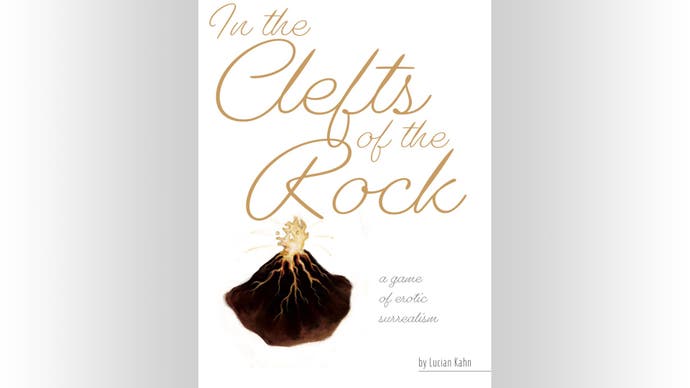

The idea of stories layered onto our bodies is perfectly encapsulated in Lucian Kahn's game In the Clefts of the Rock, part of the Honey & Hot Wax anthology of games about sex I co-edited for Pelgrane Press. Players simultaneously take on the roles of explorers traversing fantasy landscapes and the landscapes themselves that other players are exploring. They are invited to touch others' bodies in agreed-upon ways and co-create what these landscapes are like. I ran this game as part of a workshop at CLAW, and it was delightful observing so many people touch and look at each others' bodies in new ways.

Lucian's game questions the "truths" and "fictions" we clothe ourselves in. "My body is an active volcano on a far-off moon" is only a step away from, "My body is fat", or "My body isn't manly"; In the Clefts of the Rock urges us to re-examine preconceived notions about ourselves, how we like to be viewed, and how we like to be touched. It's the ludic version of Tidal: hands and sounds wash over naked bodies, imbuing them with new meanings and stories.

We like to think of ourselves as civilised. Marvels of engineering to hold and carry us, the virtual world at our fingertips. But it's good to be reminded — through art, through games, through porn — of our flesh and blood, of the wetware of our bodies that inform the entirety of our experience, that we use to lap at the ocean, to explore a world both mundane and fantastic, to touch, to be touched, to connect...