Arcadeware - A Glance Through The Coin Door Of History pt. 2

Silicon beneath the surface.

In ten years, the arcades had pushed forward the boundaries of interactive technology more than NASA had achieved in two decades leading up to the moon landing hoax. And the industry had learnt some hard lessons, paving the way for both revolution and devastation throughout the silver age.

A few years on life support and the videogame industry once again dared to dream of flowing, silver rivers running to and from their coin boxes. The JAMMA standard had served its purpose perfectly and changed the way game developers viewed the woodwork and wiring of their machines. But this new model for compatibility in the arcades wasn't a new idea - it was exactly how home systems had always worked. Gamers shelled out a reasonable, cost-covering price for the hardware, then profits rolled in by supplying a healthy stream of new software - "Give away the razors to sell the blades" as Gillette's marketing gurus once said. Capcom saw no reason why this doctrine couldn't apply to the slowly recovering arcades, too.

Capcom Play System

JAMMA had set the arcade cabinet free, but the game boards were still a one-shot system. The intricate and costly design of the electronics was rarely recycled, and once a game had seen its share of coinage it was retired to the digital knackers' yard. Technology moves quickly, this is true, but in retrospect it does beggar belief that so much silicon was viewed as disposable. It was an archaic method of producing games, and in 1988 Capcom went one step further in building a multi-use arcade cabinet, and rescued a significant portion of the market in doing so.

The Capcom Play System 1 debuted with the well-respected shmup and third instalment of the Jet Pack trilogy, Forgotten Worlds. The CPS-1 was a new concept in the arcades (even though home consoles had been doing it since the very beginning), consisting of a basic control shell which connected to a JAMMA standard cabinet, but accepted additional "daughter board" PCBs containing the actual videogame. Owners of a CPS arcade cab now had the opportunity to replace just the software PCB, and no longer shed the electronic innards of their stale games.

The system board was a monster of gaming technology designed specifically to cater for the hard, fast "'em-up" style of games that were seeing a resurgence in arcades across the world. Although the screen resolution was still geared to suit the standard monitors found in most JAMMA cabs, the 12-bit RGB colour, 10MHz Motorola processor, wealth of dedicated sound capabilities and easy user installation made it a potential revolution in floor standing gaming.

The reduced hardware costs, rather than technical aptitude, were the enticement for starving arcade operators, but ultimately it was the games that were going to determine the future of Capcom's bold venture. During its short, but prestigious lifespan, the CPS-1 brought over 30 classic (and not so classic) titles to the coin-heavy coin-op gamer from seminal shooter sequel 1941, through platform legend Strider and beat-'em-up beauty Final Fight.

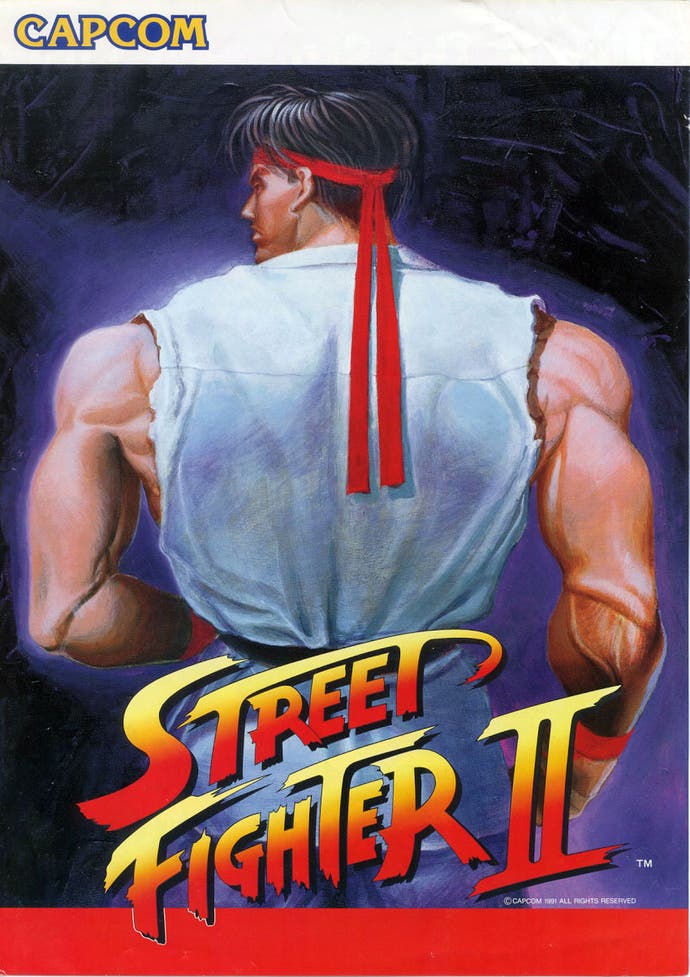

But what really launched the CPS-1 into worldwide industry recognition was Street Fighter 2; a title that requires no introduction and by its mere mention provides you, dear reader, with an explanation as to the success Capcom's arcade system enjoyed. Unfortunately for Capcom it also brought another prolific trend from the home games industry to the sticky arcade floor; piracy. Bootlegging of the game boards was rife, especially once the Street Fighter sequel brought the coin-op industry back to life in a way not seen since Pac-Man.

This wasn't the first time arcade hardware had been plagued by clones. It might seem like a task that's far too monumental to be worthwhile, but recreating complex electronic systems for the sake of reeling in a box of 10p pieces was a side industry that supported itself quite admirably. Street Fighter 2 made that illicit practice all the more tantalising for software swashbucklers, and unfortunately the CPS-1 system was completely unprepared. At one point, hardware rip-offs of SFII were as, if not more, prevalent than the official boards, and what with the generic visage of a standard JAMMA cabinet for camouflage, an illicit copy was almost impossible to spot.

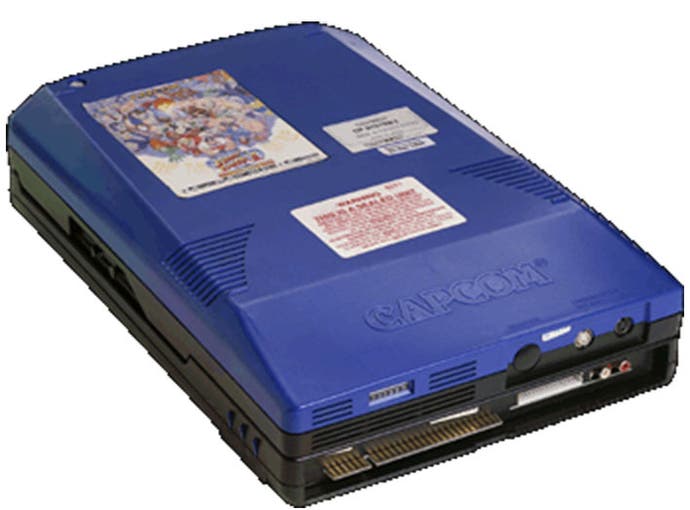

To counter act this profit sapping problem, the only real solution was new hardware - the CPS-1 simply couldn't be hacked to protect the games. In 1993 the CPS-2 was released to carry Super Street Fighter 2 to glorious, encrypted grandeur.

Essentially the same hardware, only with a diabolical encryption system and a colour coordinated plastic casing, pirates were stopped in their tracks by the incredibly high levels of protection surrounding the code. It wasn't until 2001 (long after the CPS-2 was out of play) that the encryption was finally cracked, though another, unintentional, stumbling block was placed under the feet of would-be code assassins.

The CPS-2 game boards used a battery backed up memory containing the decryption keys necessary to unlock the game, but as they years dawdled by, these batteries died - taking the unlock codes with them.

Whether or not this was an intentional self-destruct system (it seems unlikely, although suspicion arises as Capcom still provide a modestly priced service to replace lost decryption keys in CPS-2 "B" boards) it's difficult to say, but the "suicide battery", as it's become known, is a constant thorn in the side of arcade collectors.

Almost as many games were released on the CPS-2 system and its predecessor, though the arcades were a changing place (once again) and the sheer volume of units sold didn't nearly compare to the developer's first incredible concept that silently revolutionised the arcades.