Akka Arrh review - Llamasoft returns with intrigue and delight

Legit.

I don't know if you've ever worked with oil paints, but the point of them is simple: you can move them around pretty much forever. Oils take an eternity to dry, which can be really annoying if you're delighted with what you've done and want to get it varnished. But the upside is absolutely filled with upness - it's front-loaded with upness. You place the paints on the canvas and you are absolutely not committing yourself to anything. For the next few hours and days you can take a brush and just move that stuff around, blending, reshaping, reworking, completely transforming whatever you touch.

Anyway: I think Jeff Minter works with code in a similar way. It's part of why his games are so hard to understand at first, or to be more precise why I have found that they're so easy to misunderstand. Oh, Space Giraffe is Tempest again? Well, maybe it was at first, but that's really just how he started out with the canvas. Then he started moving stuff around. And then he started moving that stuff around. And then he was reshaping, reworking, seeing what pleased him and rebuilding everything around that. Minter has said before that he doesn't see his job as rendering a set design document in code. Look back at his games and there's always a starting point - a template, often an existing arcade classic - that is then transformed by moving all the paint until something new emerges.

This is true with Akka Arrh, I think. In fact, maybe it's never been more true than with Akka Arrh. Minter has described his latest arcade treat as a real-time strategy game, or even a tower defense in which the player is the tower. Also this: it started its life as an Atari design that never quite made it to full production. True to form, when I started playing Akka Arrh, I started by mis-thinking. Oh, I said, this is Tempest again, but inverted. You're at the bottom of the well and at the top of the well. I had forgotten the process, of course. The reshaping, the reworking, the serious work of seeing what pleases from one moment to the next.

The rewards of such a way of working cannot really be overstated. Akka Arrh takes a long time to click - it did for me at least. This is because I was looking for an easy way in, and there is no easy way in here. (That said, I do recommend switching out the default one-button control to a two-button option.) But when it does click, it clicks on an entirely new level. It clicks deep - subcutaneous deep? Deeper still - a thrill I feel in my bones, my marrow. This is a game with a lot going on - more than any Minter game since Space Giraffe it gives you an astonishing amount of things to keep in mind as you play. And yet, because of the way it slowly transformed itself in Minter's mind and eyes and hands until it reached this current state, its complexity is just waiting to melt away to reveal something that feels pure. Pure understanding. This game puts you in the zone.

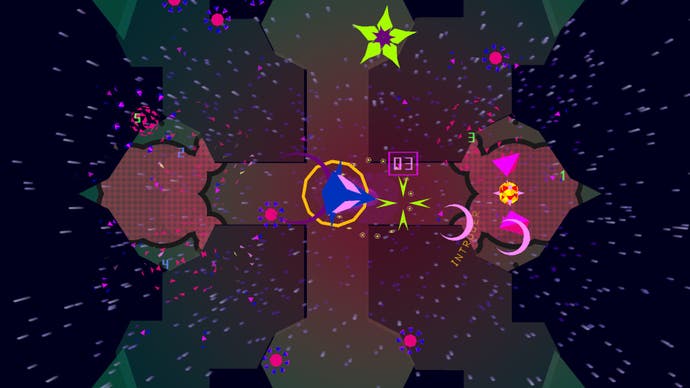

Oh god, how to explain this? You control a ram's head tower thingy at the centre of the playing field, a playing field that will transform from one level to the next, warping between flower shapes, medieval bosses, crosses, often growing separate heights of platform as it goes - separate tiers to manage. Enemies attack the tower, trying to steal the pods you have there, which count as your life force. All pods gone? You're dead. Anyway, stay with me: you can kill a lot of these enemies by dropping bombs on them and then catching them in the shockwave that rushes out from the point where the bomb connected. Any of these ground enemies caught in the shockwave will obligingly die and trigger their own shockwaves.

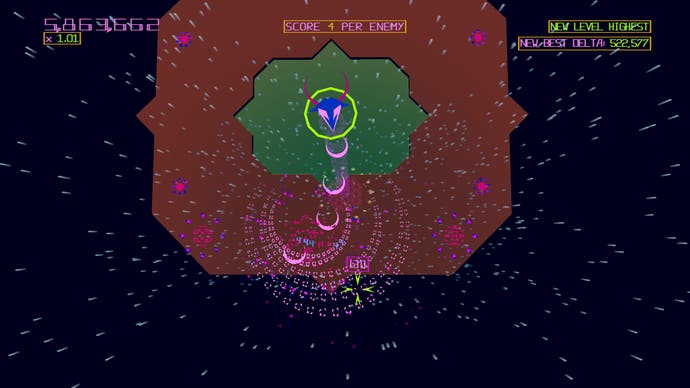

Chain it! A combo starts to build and the point is to keep it climbing. This is how you score big points! You can drop as many bombs as you want, but they each reset the combo, so use them sparingly. Akka Arrh wants you to be elegant. To find that perfect place, that perfect moment, that perfect configuration of incoming enemies in order to create a wave of bombing that never has to end.

More, though. There is more. Firstly, when there are different tiers of platform in play, a bomb will only clear out enemies on the tier in which it's dropped. And then - did you see this coming? - there are enemies who are unaffected by bombs. These enemies require bullets, which you can shoot in all directions from your rotating tower. Bullets - did you see this coming? - are earned by enemies you take out during bombs. So bombs are infinite but should be used sparingly because they reset your combo, while bullets don't reset your combo but should be used sparingly because they are not infinite.

From this design, an awful lot of magic happens. On the simplest level, you get whole stages which are designed to be solved, and completed with just a single bomb drop that leads to endless, rippling consequence. It's chaos, but underneath it's actually choreography. That's elegance. But Akka Arrh is great because it acknowledges that you will be inelegant some of the time, and it gives you both tools and consequences. Tools like power-ups you can collect, or lucky moments where a bullet goes exactly where it should and saves you from disaster. Consequences like that awful feeling when bomb-proof enemies converge on you and your pods and you realise that you have no bullets left, that you're wide open, that it's all your stupid fault.

Fault. Let's go a bit deeper here, because the more I play the more I am certain that managing fault is at the heart of this game. It's not about purely succeeding, it's about understanding all the ways you can fail and avoiding them all. And it cues you in constantly: end a chain by dropping another bomb and the game actually kind of boos you. Or at least the unseen audience lets out an empathetic groan. Finish a level but only by spamming too many bullets? You'll be penalised for not holding onto enough of them. Suffer an intrusion in your base and your bonus disappears. Succeed, the game is telling you, by shutting off these basic avenues of not succeeding.

Play more and you'll discover gimmicks and twists and one-shot moments of brilliance emerging from the central idea. There's a surprising amount of Space Giraffe in here, with Tennisy-enemies that want to engage you in volleys, and all those sound effects - the ringing phone, the cat on the piano - that are trying to dial you into specific events. But still at the heart of it, the rigour that makes it so replayable: everything matters here. You have to keep an eye on different enemy types, different levels of play, the state of your various resources. You even have to learn about Going Downstairs - during those intrusions, when your tower is swamped by enemies so you have to descend down this lurid tube to clear out your base close-up, blasting away at any enemies that have gotten too close. It's awful and brilliant - the panic of needing to be in two places at once. Akka Arrh, for all its other strengths, is a wonderful simulation of what it feels like when the doorbell goes just as you have a bath running.

It is all delivered in classic Minterania, too, from sitars and cut-up samples on the audio to witty, often helpful text and strobing Robotron colours. For all its digital abstraction, throughout the game, there's a strong sense of being privy to a body's inner workings here. Basic enemies look like flu viruses covered with spike proteins, while there's something of neuroglia to the swarms of subsequent enemies that swim around. All tower defense games are sort of about homeostasis and the immune system, I guess, but it's hard not to imagine that this hectic battle is taking place under a microscope.

How to find words for what Minter does? His games create their own terminology of course - in Space Giraffe you can perform bull runs and also trim the flowers - but after a few sessions I'm reaching for the microscope or struggling to pick through the magpie allusions that emerge. You know, Every Extend with its expanding boundaries and chains, Robotron again with its swarming, differentiated horrors, and, yes, Tempest with that central tube. Defender? Why not, with the way it dices your attention like a sushi chef, and beyond that something crosswordy that I cannot quite put a finger on in terms of the manner in which you sometimes sense each level has a single solution, that these spaces are secretly machines just waiting for you to find the only right way to put them into motion.

All of which is to say: cor. Cor! I know I'm still early on in Akka Arrh, not just in playing it but in working out exactly what it is, and exactly what I most love about it. No surprise here I guess, since it took me years and years to come to any kind of understanding of Space Giraffe, to start decoding and translating the wordless joy to be found in that 50 MB package. But that's part of the way these games are made, right? Part of the benefits of moving paint around. Turner painted like this; there's a wonderful story about a child watching him paint and the canvas is just colourful flux for an entire morning before suddenly a sailing ship appears, complete with complex rigging. That's Minter too: a mixture of speculation and growing decisiveness, and perhaps that's the artistic tradition Minter most belongs to as well. Here, fully revealed, is a digital Romantic, and what he can show us is almost overwhelming.