After Lemmings was a hit, DMA Design declared war with Walker

Here comes the hot stepper.

Usually, you wage war in order to take over the world. DMA Design did it the other way round. In the early 1990s, their crowd-control mega-hit Lemmings was an irresistible love bomb that won hearts and minds by appealing to the benevolent dictator in us all. Despite its cutesy appeal, Lemmings wasn't a game free of violence - far from it. You could always order your entire green-and-blue army to self-destruct, the little critters exploding in sequence like microwave popcorn. But the main thrust was saving lives through engineering, creating a secure route for your daffy charges and allowing them to shuffle to safety. DMA Design conquered gaming without firing a single shot.

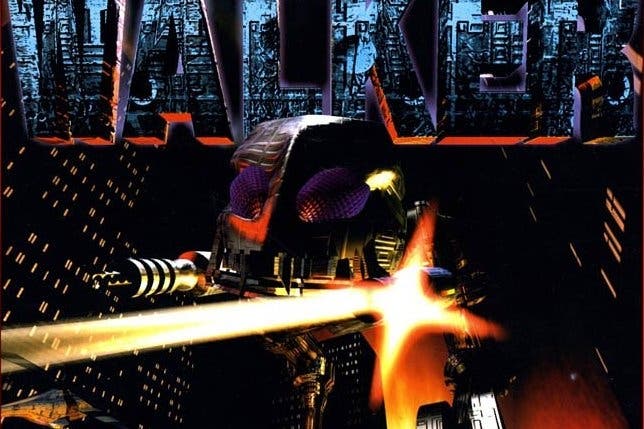

For their follow-up Walker, released for the Amiga in 1993, the developer chose a very different path. Two decades on, it almost looks like a Titanfall demake - a side-scrolling 2D shooter where you control a beautifully animated bipedal mech, perforating waves of enemies with the brace of heavy machine guns slung under your cockpit. The walker's bright blue head, which convincingly tips and swivels to track your targeting cursor, seems slightly incongruous when placed against the game's drab backdrop of shattered warzones, but it means you're always entirely sure where you are on-screen, even when struggling to pick out teeny foes in the murk.

Walker piles on so many quirks and restrictions that collectively they begin to resemble innovation. You control your mech using a combination of mouse (to target and shoot) and keyboard (to stomp your war machine forward). Forward, in this case, is moving left: Walker rejects side-scrolling scripture by making you advance from the right of the screen. This shouldn't have any tangible impact at all, but it goes against so many deeply embedded gaming instincts that, at first, it seems genuinely alien and unsettling, like watching the hands on a clock move backwards. It makes Walker memorable, an eccentric southpaw.

Perhaps the sensation of moving backwards is deliberate, given Walker's time-travelling gimmick. There's an almost hilarious lack of plot, but each of the four missions takes place in a different timezone, beginning in Berlin 1944. What these historical enemies lack in technology, they make up for in numbers, throwing ragged infantry, dinged-up tanks and volatile airships at your lone walker. You quickly realise Walker is a game of tactical prioritisation, working out where best to focus machine-gun fire and timing bursts to ensure your weapons don't overheat.

Waves of tiny, Lemming-like infantry can be cut down with an offhand sweep. Anything armoured takes more time, and while you're chiselling away at a truck, another foe will be advancing into a better position. The animation of enemies, when you stop mowing them down long enough to observe it, is full of character. Some of them are actually charming. Can you really bring yourself to shoot the horses pulling artillery into position? It's your choice, but the chaos is compelling. Every explosion creates a satisfying "whump" and throws a shower of flaming debris around the screen. Moment to moment, Walker is a blast.

The other three levels flash you forward to a Terminator-ravaged Los Angeles, 2019, the contemporary Middle East (solemnly time-stamped as "tonight", which seems as ill-judged now as it did in 1993) and, finally, the 25th century, where the entire planet has seemingly transformed into a bombed-out HR Giger theme park. All the resources that went into perfecting your time-travelling tech clearly had a deleterious effect on weapons R&D - there are no power-ups or upgrades in Walker, so the steady rattle and pinging ricochets of your machine-guns also serve as the unending soundtrack. Sometimes, you find yourself wishing for a laser or a flamethrower or an oversized grenade you could kick like a football, just to mix things up.

There are other little things that hobble Walker. Your mech is an odd combination of power and slapstick. Despite striding purposefully forward, you can only clear one screen at a time. Standing still is suicide, so each firefight requires a little chicken dance - a few steps forward, then back a bit, then forward again - to ensure you don't take too many hits while you're spraying bullets. Thankfully, the resonant, servo-assisted clang of your mech in action never gets old - it puts you in mind of RoboCop's deep drumpad stomp, the heavy tread of Ripley's power loader or the sheer relentlessness of Lee Marvin in Point Blank. But for anyone watching rather than playing, the sight of a heavy metal murderbot ping-ponging back and forth in one corner of the screen just looks ridiculous.

In 1993, DMA Design's other timeless gift to gaming, Grand Theft Auto, was still a few years down the line, and while it's tempting to try and characterise Walker as a stepping stone on some pre-ordained path from the little green-haired guys to Liberty City, it really feels more like a random detour. Compared to the multi-platform splurge of Lemmings, the fact that Walker was only ever released for the Amiga underlines its status as a self-contained outlier. The control requirements of using both mouse and keyboard would have made it tricky to port to consoles but that doesn't explain the lack of an Atari ST version, an oversight that seems almost like a deliberate diss when you consider Walker's primary asset is so clearly based on the AT-ST from Star Wars.

Or maybe DMA just realised Walker was good, but not great. The steep difficulty level and grinding gameplay outweigh its considerable artistic achievements, and the lack of a framing narrative means it can feel more like a polished tech demo than a game. You could weigh Walker's three Amiga diskettes in your hands to try and discern some deeper meaning or meditation on war: how it never changes, how technology can trump tactics (and vice versa), how it's impossible to get through the experience unscathed, physically or mentally. The lack of plot and disinterest in mythology could even be deliberate. Perhaps war is the same, whether it's being fought in 1944 or 2420, and when you're in the middle of a desperate firefight - in danger of being overwhelmed just as your guns are overheating - the reason you are there simply isn't important. There is only combat.

But secretly, I like to think that by completing all four levels, you close an aberrant time loop. And by successfully suturing the future, the whole Walker timeline winks out of existence. No-one will ever know of your heroic deeds, or that you shot those horses in 1944. The full story - whatever it is - will simply never be told. It's a theory, but not one I've been able to empirically test, since for the last two decades, I haven't been able to get past level three. But I'll get there. One step at a time.