20 years on, Max Payne is as stylish as ever

Hardboiled.

You've got to give it to Remedy: they know how to start a story off with a bang. As Max Payne opens, our antihero is on the summit of a skyscraper while sirens wail in the gloom below. "They were all dead," Max says with that famous frown. "The final gunshot was an exclamation mark to everything that had led to this point."

We go back a few years next, to the brutal double murder of Max's wife and newborn child, then follow his revenge mission (guns do the talking, and two wrongs do indeed make a right). By acts two and three, the guns are bigger and the body count has mounted while the web of lies are slowly untangled. The next thing you know, the dénouement comes again - Max back on his perch above the tinny whine of those police cars.

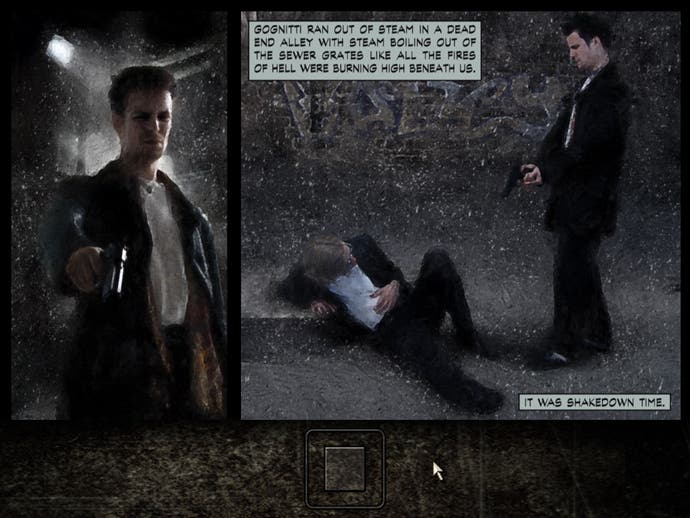

Starting at the end and coming full circle means Max is able to narrate the entire tale: a classic literary trick that more games ought to use. The meat of Max's bone-dry narration overlays graphic novel panels that come at the chapter breaks and during levels as well. I spoke to Kiia Kallio, who was in charge of bringing the panels to life. "Initially there were ideas for doing video cutscenes," Kallio tells me, "but there was no budget for that, so graphic novel panels were used as an alternative method of storytelling."

The first few storyboards were made by putting photographs beneath watercolour paper on a light table; the watercolour was added by hand, and then everything was scanned back into Photoshop. "This was adequate when the script contained about 50 pages," Kallio says. "But when the graphic novel pages grew beyond 100 - with no end in sight - and more and more story was getting written, it became obvious that hand-painting everything was not an adequate solution."

As is common in game development, levels would also change at the last minute. The upshot was that Kallio had to keep redoing his work. The solution? A custom watercolour filter developed for Photoshop that would produce the right look without needing an artist to painstakingly paint everything. The multi-layered image could be adjusted on-the-fly, enabling the team to make changes and work faster.

About 250 pages appear in the final build and I'd argue they're essential to the Max Payne experience. This might be a classic third-person shooter on the surface, but the novel storytelling techniques and occasional hallucinatory dream sequence make Max Payne feel like the work of independent artists trying to do something new. Traditional cutscenes - even if executed well - would have robbed the game of this charm.

Still, we can't go any further without talking about Bullet Time. The mechanic, which drew parallels with The Matrix, was rare in games. Yet it was relatively easy to achieve: a simple matter of setting the time scale while ensuring the camera and cursor were unaffected. "Seeing how cool it looked," Peter Hajba tells me, "we were going to have some shootouts that would occur in slow motion. But then Scott Miller and George Broussard of 3D Realms suggested we turn it into a gameplay mechanic that can be controlled by the player instead. And thus Bullet Time was born."

Hajba was there from the start and wore several hats during development, taking care of sound and visuals on the game's four-year production. He added real-world sounds to the graphic art panels ("foley tracks") and was instrumental in the lifelike animation too. All these years on, there's still something pleasurable about entering a room and launching Max into a slow-mo dive as gangsters fall like dominoes. Extermination complete, Max leaps back to his feet like a master of the martial arts. It feels suitably stylish.

Style is everything in action cinema, and Max Payne borrows a lot from John Woo's films. The references are everywhere you look, from the Easter Eggs hiding in plain sight to the script, which is pure hardboiled crime fare. (Max tells us that a security panels lets out a "mocking cackle"; that New York is "drenched in gloom"; that "death is in the air at Roscoe Street Station.") On the ground proper, a helpful pause button gives you a 360-degree view of the scene, letting you get snaps of Max in vintage poses. It all feels ahead of its time and very cinematic indeed.

Ironically, in its earliest form, Max Payne was played from a top-down perspective like Remedy's first title, Death Rally. Thanks to improving GPUs, the decision was made to stick the camera behind its titular protagonist, giving you the best view in the house and the chance to direct the carnage like a director on a film set.

And what a ride it is. After a trip to the grimy underbelly of a city subway, you head out onto the snow-capped streets of New York, then a gambling den, then a shipyard, then a mobster's mansion - and so on. Death comes quickly, but a progressive difficulty curve lessens the challenge. Still, it's wise to scour the largely linear levels for painkillers and pop them before Max's health expires (or, rather, before the health bar fills to the brim - a slightly strange design choice in hindsight). Incidentally, all those mobsters you're shooting? "Many of the actors were found among the friends and family of the developers, and even a few faces from another company in the building," Peter says. The same goes for the characters that appear in the graphic novel panels. "The budget of the game was not exactly huge" - and costs had to be cut accordingly.

Of course, the biggest unintentional star was writer Sam Lake, who provided the likeness for Max. Sam volunteered himself for the starring role. This wasn't such a big deal at first, since all the textures were hand drawn and the likeness wasn't a match. But when the team started experimenting with photos as source material for textures, Sam became the man. Alongside the gaunt Scandi cheekbones came a wardrobe that was part flea market, part high fashion.

Max Payne is 20 years old, then, but the men who helped bring it to life are still working in the business. Kallio is at Siru Innovations, a company that provides architecture for desktop GPUs and game consoles. As for Hajba? He left Remedy in 2011 and moved to Avalanche Studios in Sweden as a sound designer. He worked on Just Cause 3 and Rage 2 but has gone back to doing particle effects as well. "It's been fun. Variety is good."

In the end, a talented team managed to make something feel very grand on a small budget. When Max Payne 2 came around, the kitty was bigger. "We could hire real actors as models for our characters," Peter remembers. "Animated cutscenes could be made with motion capture. More programmers and artists joined our ranks. The whole project could be finished faster." Yet if you want my opinion, the first game is more memorable. It feels more daring, more stripped down, more punk. I also prefer Sam Lake's Max to the "true" actor hired for the sequel (Timothy Gibbs). A third game was to follow years later, but by this point, Remedy had moved on.

Still, they hadn't forgotten the lessons they learned. Traces of Max Payne linger in all their subsequent work; a third-person camera; style in spades; and most crucially, a fixation on story.

In the end, Sam Lake's stint as Max lasted one game, but I like to think that in between writing projects, he finds time alone to stare at himself in the mirror and make the face - the slightly constipated frown that would be solid meme gold were the game released today. In fact, fans still find him on Twitter to demand just that. A lot of time might have passed, but as it turns out, some antiheroes aren't easily forgotten.